Not Fade Away

I’m beyond your peripheral vision / so you might want to turn your head

~Ani DiFranco

’70’s VW; Photo: Chad Cliburn

The night before Thanksgiving in 1995, while driving home from college, my friends and I were pulled over in my ’73 VW Bus. The State Troopers claimed to smell pot as their probable cause to search. Though we had smoked none, they found enough that everyone was arrested for possession of marijuana—everyone but me. Rather than call a tow-truck, the troopers left me on the side of the road, in thick fog and cold darkness, to reassemble the remains of their search scattered in the breakdown lane.

We were criminals: dirty, smelly, music-loving, non-violent criminals. I carried a wallet size version of my Miranda rights printed by the ACLU and distributed in parking lots at Grateful Dead shows. By the time I was eighteen in ’95, I’d toured three seasons with The Dead and would soon drop out of college with my friends to drift around the country with other orphans of Jerry Garcia’s recent passing. We were dreadlocked white kids wearing handmade patchwork clothing. The word we used to describe each other on tour—our massive bedraggled tribe of music-devoted wanderers—was “family.”

In 1995, embodying this version of visible other, I’d never had a conversation about co-opting or appropriating culture. I fit in with my “family” while standing out to my family of origin. I was searching for some sort of freedom, a search I knew was permitted by my middle class whiteness. Now I recognize rebellion; I hadn’t learned about freedom yet. A few years later I took off my hippie clothing and chopped my hair. Within a few months, with a chin length bob, I was once again invisible in my simple whiteness. I dismissed an identity. I went back to school and studied writing, for a time. I still love The Dead, but I don’t look like I do.

* * *

Fare Thee Well 2015, San Jose

The cloak of invisibility that I’ll earn as a woman turning forty will soon fall around my shoulders.

It’s taken me all my life to understand we choose some identities, and others are chosen for us, applied to us, often against our will. We’re classified into corners, caged by labels. In my youth, I chose to be visibly other, claiming one of the longest-running images of counter-culture for myself: the Deadhead. My middle class whiteness allowed this shape-shift. It’s taken me time to understand that most people can’t choose.

I’ve been thinking about this lately with urgency, as my visible days are in decline. At first I thought I would rage against this. Hey, look at me, I’m still here. But when others long for anonymity, instead I consider ageism, with its accompanying invisibility, as a place from which to empower. Can this invisibility serve to hold space, to shield? To resist?

Can this invisible space be more rebel base, less cage?

* * *

A sixth grade bully first branded me as different when I was ten years old. Our vocabulary didn’t include othered. What I’d done to merit her derision and attention was choose to spend my time at the barn instead of with the girls from school. Knock-kneed skinny and “flat as a board,” I was easy to ridicule. I was taunted for the rest of middle school, and spent that time, well into high school, desperate to be invisible. Then, as happens, something changed in my teens. I wanted to be noticed. I assumed the mantle of Deadhead, characterized with the uniform of my chosen tribe.

Marblehead Lighthouse; Photo: Jake Lewis

During my youth in my upper-middle class exceptionally white hometown on Boston’s North Shore, we scorned but did not fear police. We ran from the cops regularly, but it was like a game. Our teenage armor lent arrogance, but law enforcement was never an actual threat to us, more an inconvenience. We drove around smoking weed; we climbed the lighthouse and smoked weed; we dragged a four-foot bong into the nature preserve and smoked weed. It was our white privilege to be considered by police as bemusing instead of threatening.

* * *

By my thirties, I’d learned the art of hiding in plain sight; you might have called me ordinary, though deviance was just beneath my business-casual veneer. My anti-authoritarian insides were hidden. I could party like a mid-90’s raver on the weekend and show up for work on time Monday morning. When I learned to blend in and mimic, I found joy in covert nonconformity, how so much fits under a Banana Republic Factory Store disguise. But I was waiting for something.

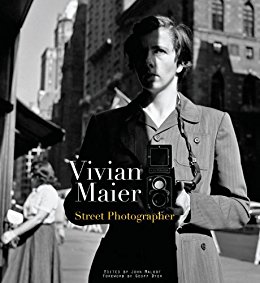

I stumbled into the Chicago History Museum on a blustery rain-cold October day in 2012 and saw an exhibition of work by street photographer Vivian Maier. Her urban portraits are stunning. She gets people, lays souls bare on film. I was surprised I hadn’t seen any of her work before, and learned that she’d made a career as a nanny. Photography was her hobby. Her genius was bolstered by her invisibility to the subjects of her lens. A tall middle-aged white woman toting a few children around, Maier went unnoticed. And she preferred the Rolleiflex camera, held at chest level, so many of her subjects remained unaware they’d been photographed at all.

Vivian Maier: Street Photographer book

I hadn’t heard of her because no one had: homeless late in life, she was “discovered” as an artist when cases of her negatives were auctioned off from storage units she’d failed to make payment on. Her work wasn’t shared with the world until the year she died. Learning about Maier, I named a certain fear I’d fostered. Worried I’d be the Vivian Maier of writing, undiscovered until after death, or never discovered, I’d been doing nothing, waiting for the prophecy to fulfill. But I had it wrong. While focusing on Maier as undiscovered, I missed her enormous power in making art from invisible spaces.

My fear was born of precocity. I was first-born and started school young, remained the youngest in my grade until I graduated high school. My youth was celebrated when I succeeded at things, at everything, academic and extracurricular. I’d wanted to be better than, but also younger than: to be the youngest rider on the US Olympic Equestrian Team; the first female NFL ref; a 5 Under 35 writer. I kept track, for a time, of all the things I couldn’t be first at anymore, tallied them in my failures column.

My young work had been celebrated. Precisely because there was promise in my young work, I set it aside and pursued other things. I didn’t get back to writing until I was thirty-eight, stalling until I was effectively too old to be first at anything. I’m long past 30 Below 30 territory, and find myself suddenly thankful for these failures. Beyond thankful. From here I can fly under the radar. This is a secret space in which to experiment and fail, where no one sees me. My age makes me invisible. There is freedom here.

* * *

We don’t have the right labels for a woman past her prime. I’m neither MILF (I have no children) nor cougar (I don’t frequent clubs), yet I’ll inevitably be forty. What will they call me next, simply old? Will they see me at all?

I’m afraid of many things. I will (or at least would) gallop a horse across country over obstacles, but I’m afraid of snakes, sharks, post-Obama America. And aging. My existential fear of aging bottomed out earlier this year. I wondered if I could reframe the term “cougar” to fit. What is actually wrong with a woman on the prowl and why must her prey be younger men? Who is a cougar without this prey to define her? She’s badass, that’s who she is: mountain lion, puma, panther, catamount, ambush predator. A cougar doesn’t roar but her wail can be the harbinger of death. She hides in the shadows and waits.

It’s all happening. I can reasonably count the days until I’m forty and invisible. I’m suddenly ready for this liberation. I’ll fade to nothing. And finally have the space to write. Everyone says they never thought they’d make it past thirty. I spent my thirties waiting for my demise, living on borrowed time; I’d surely never make forty. But here I am, done waiting.

In my youth I rebelled, cast around for allegiance, sought shelter among my tribe. Is that what we all want most, the comfort of family, however we define it? At different times in my life I’ve found the family I needed: the young horsewomen of Windrush Farm got me through middle school; Deadheads got me through my teens into my twenties; poet-warriors have my back now. And we are building an arsenal of words.

Here I am, with a perfect business-casual camouflage hanging in my closet. It’s better that you don’t see me coming. I’m supposed to be quiet and not crowd your view. Invisible. Old. A cougar with no roar. You’re counting on that from me. I’m hiding on your six.

Here I am, with a perfect business-casual camouflage hanging in my closet. It’s better that you don’t see me coming. I’m supposed to be quiet and not crowd your view. Invisible. Old. A cougar with no roar. You’re counting on that from me. I’m hiding on your six.

A great many of us, women of all diversities, have just been denied seeing power in our image, in a rage of misogyny, one among myriad discriminations of America’s gentler fascism. All of us who identify as women have been labeled unworthy. I’m gutted by the US election, as are all artists and humans I know. As my friend Mary recently wrote about, I longed to be affirmed. Our cage is glass. But we’re nasty. I’m nasty. You simply cannot contain all of us.

When my cloak of invisibility falls, I will embrace it and rage against it. I claim sanctuary in this space called “old.” I can hide here and work to crack foundations, choose words to disrupt. As I prepare to shoulder my cloak, I give thanks for the privilege to write, to share my words with you. We’re just getting started.

Katelyn Keating serves as Editor-in-Chief of Lunch Ticket, where she formerly edited the Diana Woods Memorial Award and the nonfiction genre, and wrote essays as a staff blogger. She’ll earn an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles in 2017. Hailing from New England, she lives in St. Augustine, Florida, with her husband, two dogs, three cats, and several of her parents. Her work is forthcoming in Crab Orchard Review and the anthology, What I Found in Florida [U Press of FL, 2018]. Follow her on Twitter @katelyn_keating.

Katelyn Keating serves as Editor-in-Chief of Lunch Ticket, where she formerly edited the Diana Woods Memorial Award and the nonfiction genre, and wrote essays as a staff blogger. She’ll earn an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles in 2017. Hailing from New England, she lives in St. Augustine, Florida, with her husband, two dogs, three cats, and several of her parents. Her work is forthcoming in Crab Orchard Review and the anthology, What I Found in Florida [U Press of FL, 2018]. Follow her on Twitter @katelyn_keating.