Now More Than Ever, Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé

(What the white man say?)

A piece of mine’s

That’s what the white man wanted when I rhyme

“Untitled 3,” Kendrick Lamar

In my small mountain hometown of Bailey, Colorado—filled with rednecks, conservative Christians, new age hippies, construction workers, adventure enthusiasts, and commuters to Denver, most of whom, like me, were white—I grew up knowing only two black kids. South Park is pretty much an amalgamation of the towns of Golden, Fairplay, and Evergreen, Colorado—all of which are a forty-minute drive from Bailey—and South Park, too, only has two black characters, one of whom is named, tellingly, “Token.”

Through music and literature, I became introduced to black American perspectives. In high school, rap and hip-hop weren’t necessarily my favorite genres, but I enjoyed them, and listened to them. My parents wouldn’t allow me to buy CDs or tapes with ominous “Explicit Content” warnings, but by then hip-hop had made its way into mainstream pop culture and the homes of black and white alike. I recorded songs by Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg from the radio onto blank cassette tapes with my Sony boom box. My first mix-tapes. I could play the songs back whenever I wanted.

There is a strong history in this country of colonialism and cultural appropriation. To pretend America has always been a monolithic culture of white European Christian ancestry is to be willfully ignorant of history and plain reason. Many times we profited from the appropriation.

Maybe it’s my own awakening, but I was struck this past year by the incredible string of music and literature that address race, black identity, and the black body. Albums and books that successfully dismantle and take on the dominant narrative. The narrative of white, modern, Western-European- influenced culture, that is sometimes called America.

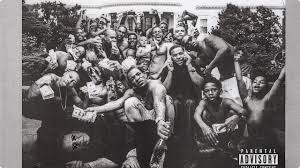

This past year, Kendrick Lamar released To Pimp a Butterfly, and Beyoncé released her visual album, Lemonade. Ta-Nehisi Coates published Between the World and Me, and National Book Award Finalist Claudia Rankine released her book of poetry and lyrical essays about the black female body, Citizen. The hip-hop musical Hamilton, which consists of a mostly Latino and black cast, was recently nominated for an unprecedented sixteen Tony Awards. The rap group Run the Jewels brought politics back into hip-hop, with members Killer Mike (black) and El-P (white) slinging take-down lyrics about the police, the state, and the church with a ferocity and intelligence I’ve not seen before. They joined forces with folks like Zach de la Rocha from Rage Against the Machine and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Indie-music site Pitchfork named 2015 the best year of rap since 1993, and Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” is practically the video that represents the Black Lives Matter movement.

The two biggest recent albums, Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Beyoncé’s Lemonade, show truly inspired artists at the top of their game. What Beyoncé and Lamar have in common is their ability to write music across multiple levels. Essentially, both Lemonade and To Pimp a Butterfly resemble novels more than they do entertainment albums or Top 40 singles. These novelistic albums require participation and engagement and operate in a variety of voices and styles. They transcend mere music.

Lemonade hit HBO for a limited release on April 23rd, and then went straight to the new music streaming service, Tidal. In Lemonade the film, Beyoncé swaggers as a proud woman, jealous wife, and overall badass/goddess of the universe. On the surface, the album is about infidelity and her rocky relationship, supposedly with her husband Jay-Z. Beyoncé spits such lyrics as “You ain’t married to no average bitch, boy,” and “You can keep your money, I got my own,” but the album also contains a diverse array of musical influences and visual styles.

Lemonade hit HBO for a limited release on April 23rd, and then went straight to the new music streaming service, Tidal. In Lemonade the film, Beyoncé swaggers as a proud woman, jealous wife, and overall badass/goddess of the universe. On the surface, the album is about infidelity and her rocky relationship, supposedly with her husband Jay-Z. Beyoncé spits such lyrics as “You ain’t married to no average bitch, boy,” and “You can keep your money, I got my own,” but the album also contains a diverse array of musical influences and visual styles.

Lemonade prominently features poems by poet Warsan Shire, who was born in Ethiopia to Somalian parents. Shire’s poems form the punctuation between Beyoncé’s songs, adding even more power, punch, and depth to the commentary on black female bodies, power, inferiority, and on. Though the album begins with the theme of infidelity, it soon delivers a manifesto on the black female experience, because more than Beyoncé’s relationship with Jay-Z, Lemonade is about race, identity, gender politics, sex, and power. To focus solely on the infidelity story misses the point.

In “Beyoncé’s Lemonade is Made for Readers,” Jamie Moore’s article for Book Riot, she analyzed the album through a narrative lens. Moore writes that the album causes us to ask the same questions as would a novel, such as, “How much of this is autobiographical/what is the context for the content?”

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, which utilizes many literary devices, including alliteration, rhyme schemes, multiple POV’s, anaphora, metaphor, allegory, and so on, can also be called a novelistic album. At the most basic level, the first-person lyrics tell about growing up in Compton (“King Kunta,” “Hood Politics,”) and touch on some larger socio-political themes (“How Much a Dollar Cost,” “i,” “Mortal Man”). The next level goes deeper—one wherein Lamar occupies a variety of voices and visions (“Wesley’s Theory”, “Institutionalized”, “Untitled I”). As the lyrics shift from one topic to another, the point of view changes, and Lamar switches voices and tempos, similarly to Nicki Minaj in Kanye West’s “Monster.”

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, which utilizes many literary devices, including alliteration, rhyme schemes, multiple POV’s, anaphora, metaphor, allegory, and so on, can also be called a novelistic album. At the most basic level, the first-person lyrics tell about growing up in Compton (“King Kunta,” “Hood Politics,”) and touch on some larger socio-political themes (“How Much a Dollar Cost,” “i,” “Mortal Man”). The next level goes deeper—one wherein Lamar occupies a variety of voices and visions (“Wesley’s Theory”, “Institutionalized”, “Untitled I”). As the lyrics shift from one topic to another, the point of view changes, and Lamar switches voices and tempos, similarly to Nicki Minaj in Kanye West’s “Monster.”

Listening to Lamar and Beyoncé’s new albums, I am reminded of our MFA Program Director Steve Heller’s presentation about voice, at our December 2015 residency. Writers, he said, do not operate using one single voice, but go in and out of many different voices throughout their works. In her seminar at the same residency, Lidia Yuknavitch spoke about heteroglossia. A term coined by Russian linguist Mikhail Bahktin, heteroglossia is the co-existence of distinct varieties within a single language or book, or in this case, album. Both Lemonade and To Pimp a Butterfly present stories outside of the “mono voice,” in opposition to the dominant, white, homogeneous voice. Both albums braid multiple narratives into their songs.

Macklemore, a white rapper, tried to tackle the issue of race in his song “White Privilege II.” Whether or not he succeeded depends on your point of view, which largely depends upon if you if you are black or white. He succeeded if you feel that he reached people who would not otherwise listen to artists like Lamar and Beyoncé; he failed if you take issue with a white man trying to address the problem of racial inequality from his position of power and privilege. The Black Lives Matter organization said that they “appreciate the effort,” and explained how Macklemore and his team had opened up a dialogue with BLM before the debut of the song.

And yet, I often wonder: Even here, writing this, am I doing the same thing?

As Lidia Yuknavitch said, if you shut out the other voices to the story–voices not typically part of the dominant cultural narrative–you are committing a colonialist act. In this way, Lemonade and To Pimp a Butterfly are two of the most important albums of my generation. They tackle the intellectual, personal, racial, and socioeconomic issues of our day. The timing could not be more pressing. With the rise of white nationalism, the current political state of our country seems to point to two very different national identities. One wishes to celebrate and propagate one cultural narrative over the others, and doesn’t acknowledge that it has been the single voice for much of our history, and that perhaps there are other lenses / perspectives out there. The other identity is the one that recognizes the varied perspectives.

I recently heard poet/speaker, Micah Bournes, talk at a church about how what we assume is “orthodox” theology is primarily white-European theology, and that this is not bad per se, but that most of us fail to acknowledge the particular lens this theology represents. A multiplicity of voices exist and have existed for many years. What Beyoncé and Lamar show us in their music is a diversity of experience outside of the mono-culture—whether it’s race or gender.

This recognition of diversity is more important than ever.

Levi Rogers is a writer and coffee roaster out of Salt Lake City, UT. He lives with his wife Cat, his dog Amelie, and his many socks, all of which have holes. He’s currently an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles.