On Learning to Fail

In fourth grade, my best friend Kimberly walked me—or rather, dragged me, my hunched body straggling two steps behind her—to Chamber Singer auditions. I’d started singing at six years old, and I idolized the girls and boys who traveled to Nashville and Atlanta and performed outside the Publix grocery store on Old Cutler. Our elementary school’s music teacher, Mr. Simon, directed the group. He’d grown up with my dad and during class asked after my family. He taught me “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” on the piano. But that afternoon, minutes after the final bell, Kimberly pushing my shoulders through the doorway, my connection to Mr. Simon didn’t matter. I was nervous and untrained. Kimberly reassured me I was a shoe in.

I wasn’t. As it turns out, training matters. I didn’t match a single note—in fact, I hit notes so wrong, once he played a middle C and I sang a low D. Kimberly laughed at my audition. Mr. Simon, gentler than a ten-year-old, suggested I review my scales with my dad and maybe audition again later. I didn’t. I felt embarrassed and hurt; I kept mum about my audition on the car ride home. For the next five years, I opted for the far less embarrassing private concerts in my bedroom and, now as an adult, in rush hour traffic on the 405.

I’m a quitter. I quit when I’m criticized, as soon as someone suggests I need improvement.

In the summer of 2012, I moved to New Jersey to participate in New York University’s Writers in New York program. I dreamed of becoming one of those writers whispered about in the White Horse Tavern, my novel in display windows along Fifth Avenue.

In reality, up to that point I’d written only two pages, entirely expository, of a short story and a few journal-style entries for a Tumblr blog I lazily titled “This is a Story.” I survived on grilled cheese sandwiches and granola bars and overpriced whiskey from restaurants in the Meatpacking District. Luckily, my instructor at NYU, Chuck Wachtel, was kind. During a private conference, he said I wrote like Mary Gaitskill. In workshop, he praised my short story: the title was clever, the characters authentic. Back in New Jersey, I revised the piece based on his few notes and promptly sent it to literary journals (and my closest relatives and friends).

What followed?

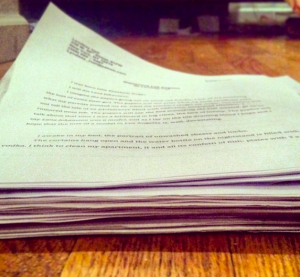

Dear Lyndsay,

Thank you for taking the time to submit to [journal]. Unfortunately, after careful review, we have decided this submission is not a good fit for us.

We wish you the best of luck placing your work elsewhere.

Sincerely,

The Editors

Times ten. And not only from well-established print journals, those at which the big names published. Online journals rejected the story, too. Editors hated it—or did they hate me? In a Nova Scotia airport after a family vacation, I decided to quit writing.

A few weeks later, I moved into my dad’s guest room in Florida and read Hemingway and ignored the short story collecting digital dust in my Documents folder.

* * *

In Mindy Kaling’s book, Why Not Me?, she recalls a panel during which a young woman asked her where she gets her confidence. Kaling says at the time she offered a “shitty, unhelpful response,” about having supportive parents. Sure, that’s useful, but it’s not enough. My parents supported my desires, but support didn’t make me confident, let alone committed to anything.

In the essay, Kaling offers a less shitty, more helpful response. In her first few weeks as a writer at The Office, she says, “Whenever [the producer] Greg Daniels came into the room to talk to our small group of writers, I was so nervous that I would raise and lower my chair involuntarily, like a tic.” Years later she realized how she felt in that writing room—that instinctual insecurity—was correct. Why? She didn’t deserve her confidence yet. She’d done nothing to earn it.

When we first start out, whether as a singer or novelist or Hollywood sitcom star, we probably haven’t accomplished much. In New Jersey that summer, I’d done nothing but receive an acceptance letter; I hadn’t completed a short story, submitted work to a journal, received criticism, or even visited the historic literary White Horse Tavern. I arrived at the Lillian Vernon’s Writers House daunted and insecure, my thumbs wrestling on my lap. When writing became hard, confirmed my insecurities, I quit. I didn’t put in the work.

To explain how she finally earned her confidence, Kaling quotes Kevin Hart’s Twitter bio, which I will quote now, also, as it’s the most apt advice I can offer:

My name is Kevin Hart and I WORK HARD!!! That pretty much sums me up!!! Everybody Wants To Be Famous But Nobody Wants To Do The Work!

* * *

Six months after I quit writing, I tried again. I decided I wanted it more than I was afraid of it.

In the summer, I submitted the short story I’d written at NYU to a workshop led by Ted Thompson, author of The Land of Steady Habits. He intimidated me because he’d gone to Iowa and he was undeniably attractive—thick framed glasses, boyish grin. Somehow those qualities made him seem like the most talented person in any room he entered, and for me that translated into respect.

In the workshop, the writers annihilated the story. Thompson said it had no scenes, and how trite was the title? He assigned me exercises—I was the only one in class assigned exercises—and requested we meet outside of class for a private conference. Was my work so poor, I required special attention? At the end of the workshop, the woman across from me announced that an online journal that had rejected my story a year before had accepted the piece she’d workshopped earlier in the session. She thanked us, genuinely, for our thorough critique.

* * *

In February, The Stranger published an essay by Ryan Boudinot about what he learned while teaching at an MFA writing program. The piece drew backlash. How dare he so outrageously suggest writers are born with talent, that you won’t make it as a writer if you don’t decide in your teenage years to pursue the art? How could a man—a white man, no less—advise students without time to write to just drop out?

I cherished this essay. I kept the essay opened in my phone’s Internet browser for months. I felt a sudden gut punch every time I saw the title: “Things I Learned About MFA Writing Programs Now That I No Longer Teach in One.” And this wasn’t because I believed I was born with talent, or I’d decided by thirteen to be a writer—I hadn’t made that decision until only a few years ago. I loved the essay because it was brutal. For a brief moment, I wanted to quit writing. Again. And then, I got to work.

At that time, I wrote under the mentorship of my toughest instructor to date. In his first letter to me, regarding a personal essay, he wrote, “The essay suffers often from glibness, from what comes across, anyway, as a desire to be stylishly urbane, a defensive cleverness that sabotages clarity, intimacy, and true emotional depth.” In the line edits, he called my writing “insecure.” He was right. I’d written sentences that sounded unnatural and literary, the result of leaning on a thesaurus and trying—and miserably failing—to mimic the style of Leslie Jamison. My mentor erased paragraphs, asked in the margins, “Do you not see the pretentious straining here?”

When I say toughest mentor, I mean best mentor. My parents held my hand, flattered my so-called talents, paid for that thesaurus. They’re good parents. But my mentor last February, and Boudinot’s essay, were the force that pushed me into the desk chair to work.

Last month, I read to a co-worker the notes my new mentor gave on my novel-in-progress. The notes were complimentary, encouraging, and I felt like maybe I was onto something with this chapter. The next day, standing in front of that same co-worker, I received an email notifying me that an anthology rejected an essay I submitted six months earlier. “We wish you luck placing your work elsewhere.” But I can’t place this elsewhere. I wrote this just for you, I wanted to scream. Appreciate that!

I wish I could end with a success story about receiving a hefty advance from a publisher, or at long last placing the piece I wrote while at NYU. But I can’t. That happens sometimes; there’s no guarantee. Most of following dreams is simply persevering.

Instead, I’m going to leave you with more wisdom from my girl Mindy Kaling, again from Why Not Me?:

“If you believe in yourself and work hard, your dreams will come true. Well… I guess the people who work hard whose dreams don’t come true don’t get to write books about it, so we never really find out what happens to them. So… if you believe in yourself and work hard, you have a fighting shot at having your dreams come true.”

Lyndsay Hall lives in Los Angeles where she teaches writing to children and teens. She is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University and she serves as an editor for Lunch Ticket, Zoetic Press, and Prague Revue. Her essays have appeared in xoJane, Rhizomatic Ideas, and elsewhere.