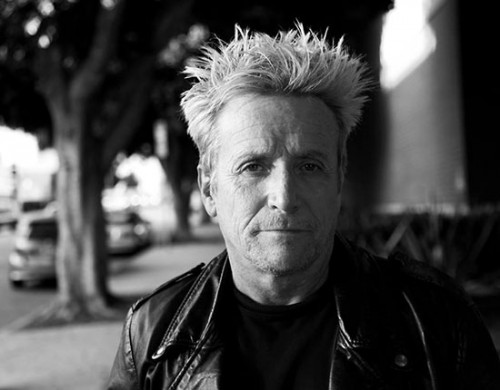

Patrick O’Neil, Author and Filmmaker

Patrick O’Neil is the author of the memoir Hold-Up (13e Note Editions, Paris, France). He is currently in the process of writing a second book chronicling his former career as a roadie/road manager for several major punk bands during the 1980′s (Dead Kennedys, Flipper, TSOL, Subhumans). His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including: Fourteen Hills, New Plains Review, Weave Magazine, Sensitive Skin, Razorcake, and Word Riot. As a filmmaker Patrick has made two documentaries: Girls on Girls and The YAA Girlz and the Deadly Sparks. A new untitled film project is currently in production. His former band, ON-X—a collaboration that produced the CD It Just Get’s Darker…—unraveled in 2008. Another music endeavor is in the works. Patrick lives in Hollywood California, holds an MFA from Antioch University Los Angeles, teaches at a local community college, and facilitates writing workshops.

LT‘s Visual Art Co-editor Ashley Perez interviewed O’Neil on August 18th, 2013, at his home in Hollywood.

Ashley Perez: What inspired you to make documentaries in addition to your writing?

Patrick O’Neil: Well I got my BFA in film from the San Francisco Art Institute. So I originally started as a visual artist in film. I also drew, and my drawings lent themselves to movement, so that moved into animation, then film. It was a long process. I was a printmaker at first, making etchings. That was back in the 70s. I got into storytelling in film. But, I basically stopped making films until recently. The old way of doing film with 16 mm and splicing and cutting and AB rolling and doing all this weird stuff is unbelievably time-consuming and technically a hassle. Whereas now with digital filming on computers and Final Cut Pro and programs like that, it’s so cool and easy. It’s my first love, so I got back into it. I started doing films for this show called Skate This Art in San Francisco. The two films I made were for those shows. It was a benefit for a local charity in San Francisco where people painted art on skateboards and auctioned them off. Local artists did that and I would make a film and show it and a band would play. That was my original motivation to make films.

AP: You had a behind the scenes role in the punk rock scene. You were a tour manager and roadie. At what point did you transition from doing that to writing and film making. Or, were you always writing?

PO: No, I wasn’t. I’m dyslexic. I have a learning disability. I transpose words when I’m writing and I transpose numbers verbally. I was a visual artist. At some point in time, I was a punk rock kid in art school, I went into music. I played with a bunch of horrible bands and other people were playing in real bands and doing well. I didn’t have faith in my own self to go out and do it but I enjoyed the limelight and started getting into the production end of it. At that point that’s when I became a roadie and a road manager and toured for a while. When that all fell apart I went back to doing art work for Alternative Tentacles, which was Dead Kennedy’s label. All that was visual. Then drug use, addiction, and crime got in the way and I didn’t do anything artistic, musical, anything for 10 years. When I was eventually arrested and then incarcerated, that’s when I began writing. I started writing in journals on my own, then going to adult education classes in jail, which was in 1997.

AP: Tell me about the memoir you are writing now about your years as a punk rock tour manager.

PO: I’m trying to write that thing (laughs). I’m having a hard time writing that book. Some parts come and it’s really easy to bring up the memories and some are lost in the fog. It’s the kind of thing I keep working on. It comes in chunks. I binge write on this one and I’m not a binge writer. I’m someone who’s really structured and puts in the work every day. This book, I open up the manuscript and look at it and all of a sudden it’s not there. I don’t have it for the day and I work on something else and do other things. It’s been a tedious and slow process.

AP: Was it harder being the road manager for some of these bands or writing about being the road manager for these bands?

PO: It was really easy being the road manager for these bands, even though they were pains in the ass musicians and being on the road is incredibly bizarre. All kinds of crazy things happened. All the things you’ve heard about touring. There was an amazing amount of alcohol and drug abuse going on. I was a strung out junkie the whole time. It was the height of punk rock. It was an amazing time. I never regret any of it. It was just easier to live than to write about it.

AP: Before we talk about Girls on Girls, are there any other projects besides the memoir currently going on?

PO: Right now I’m writing fiction. I’ve never worked on fiction before. I just read a piece of fiction, “Her Name Was Martha” in San Francisco and at Beyond Baroque for the Poets and Writers event. So I’m working on that and I work on dialogue on a daily basis. I’m trying to get my dialog together. It’s one of those things I’m really happy doing; it’s getting more attention than the book I’m supposed to be writing. Which is how it works, you know. But at least I’m doing something. I’m also playing music again, which is interesting.

AP: Is that something that’s been on hold for a long time?

PO: It comes and goes. The last CD I recorded was in 2007. The band was just two of us. We played all the instruments. It’s been six years. I actually recorded the CD as my field study for Antioch University. I wrote the lyrics and with a friend of mine, we recorded the whole thing and put it all together.

AP: Nice! Girls on Girls came out in 2010. Did you create this just for Skate this Art or was it already in the works?

PO: The first film I did was The YAA Girlz and the Deadly Sparks and that was for the Skate this Art benefit and it was about women skateboard teams in San Francisco in the ‘80s. It opened my eyes to what I wanted to do. I got interested in women’s stories that juxtapose the men’s version of those stories. There are all these men skaters that had their stories told. There were all these women skaters, underclass kind of thing so I was interested in that story. Plus, I knew all of them from San Francisco, so it was readily available. Later when I had the idea to make the other film, it was the same idea. These women and their bands that I was interested in, most of them were readily available, so it was another story of something that needed to be told. I felt it was going on the same idea, so I didn’t do it just for the project and it was more of an undertaking than I had ever done before. It was almost 23 minutes; the first film was a real short short documentary at 13 minutes. So this project was much more involved. And then using the band’s music and videos I had to get permission and deal with copyrights. It was a way bigger project.

AP: That answers a question I had about what inspired a man to do a documentary on women in punk music. It is still a controversial topic. Women in metal or punk music are still fighting for equality.

PO: Right. Well first, I find women more interesting than men. I was raised by women, not a lot of male role models in my life as a child. Second, for lack of a better word, it’s an underdog story. Women never got respect in rock and roll. There are very few bands that are all women for one, and then very few of those bands that aren’t considered a novelty act. However, I had to do a bit more research with this film. Most of these bands I didn’t know. I knew Antonia (Crane) but I didn’t know her band, Dirtbox. I didn’t know Grass Widow (the last band in the documentary) until Rob Roberge introduced me to them. The other bands were friends of mine and I used to see them struggling in this male dominated industry, still do. Basically, it was unfair. It’s just odd to revisit it years later and to take a look at it and its odd because nothing’s changed.

View “Girls on Girls,” Patrick O’Neil’s 2010 documentary about women in punk rock (32 min.)

AP: Yeah, in a day and age when we’re supposed to be progressive.

PO: What’s strange is that punk rock was fighting against these established codes and ethics and so forth, but sexism was still there. As much as people wanted to say there wasn’t, there was. It’s odd that you have these movements that are so anarchistic yet they still hold on to outdated and stupid ideas. Or phobias or fears or whatever the hell it is.

It’s odd that you have these movements that are so anarchistic yet they still hold on to outdated and stupid ideas.

AP: What’s your creative process like as a writer and a filmmaker?

PO: As a nonfiction writer, I know the story. So my creative process is making an interesting story out of the story. I think that’s the creative of creative nonfiction. It’s the author’s job to put beautiful language into their story. I’m not saying I make beautiful language, but I attempt to at least. Hopefully the story is already interesting enough but you have to make the language as interesting as the story. With filmmaking, I just go and shoot a shitload of film and interview people and then work it all into the original idea and it all comes through at the end when I edit it and put it together. But, I don’t know what I have until then. Like with Girls on Girls, the film starts out with a clip from Sid and Nancy that I took off the Internet and then a bunch of still shots, interviews, music videos, and a soundtrack I compiled, and it all came together at the end. I have a friend, Patrick McCormick; he did the post-production and fixed up all the mistakes I made. He is a professional filmmaker and I am self-taught on the computer. I never had any real training on any of that stuff. His help was greatly appreciated.

AP: On your website, it said you have another film project in the works. Tell me about that.

PO: I have two, but not much work has been done on either. They’re both in the planning stage. I haven’t found the ability to do them, one is a bit more advanced than what I’m used to doing. The other film I’m working on is about online dating and love.

AP: I can forward you some OKCupid messages from my friends.

PO: That’s one of the venues I want to use. The problem is finding people who will go on camera and be interviewed. I want to find a sex worker that’s on craigslist. I want to find someone on OKCupid and maybe a successful relationship that’s come out of there—have the subjects all talk about what love means to them in that respect. I also want somebody who goes online for casual sex, not a sex worker, just someone who has casual sex online. Have three or four women talk about all that.

AP: What attracts you to a subject as a writer and visual artist?

PO: It’s all the same thing. This may sound cheesy, but finding beauty in what isn’t beautiful. I am attracted to the dark side, attracted to sleaze and unpleasantness and awkwardness and anger and violence. I’m attracted to the dejected, the homeless, the streets, criminal activity. There’s an unbelievable comment on human nature that pervades everything. That’s what I’m trying to portray in my work, although maybe not my films yet.

AP: Wait for the online dating one.

PO: Exactly.

AP: What prompted you to enter an MFA program?

PO: I had started writing when I was locked up. I was writing all the time, writing stories about crimes and people. When I got out, I kept it up. I was writing a lot of angry stuff. I was an angry guy in those days, angry at the world. I felt I had been done wrong. Through working on myself, I started figuring out that wasn’t the case. My writing started to shift to writing stories, vignettes of daily life and I started a blog in 2004. I didn’t know what computers were until I got out of prison and I learned from scratch. I made myself post 2,000 to 3,000 words a week. I wrote stories about my neighborhood and people. I did it as an exercise and a commitment. At the time, I was a drug and alcohol counselor working at a rehab center. I was there for five to six years and the Feds came in and said you have to go to school for two years to get certified as one and I was already doing it so it seemed stupid. I would have learned more things but the kicker was did I really want to be a drug and alcohol counselor the rest of my life? Did I want to do two years of school to keep doing what I was doing and get paid the same amount of money? Was I that into it? I was kind of burning out by then and I was a drug and alcohol counselor to pay back my sins of my bad behaviors of the years before. My dad, who is a linguistics professor at MIT was really encouraging me to write and liked what I was doing. He’s my editor and is really supportive of me. He said, “If you’re going to go to school for two years, why don’t you do what you want?” I already had a BA. He was like “Why don’t you be a writer?” and encouraged me to get an MFA. I thought, you’re kidding me. I hadn’t been to school in 20 years and didn’t know if I wanted to. I kind of needed to just make the plunge and see what happened. I applied to three schools. Two of them accepted me. Antioch was low residency and it sounded like the perfect thing for me. I liked Antioch. I’ve always been supportive of their social justice mission and their politics. They were a better fit and I went with them. It gave me an opportunity to find a community that I needed to say I was a writer. I kind of thought I was a writer and felt I was a writer, but it gave me the voice to say I was a writer, to feel comfortable with it.

AP: Is there anything you want to add that I didn’t cover?

PO: No, maybe not.

AP: Thank you.