Photo Sensitivity

I opened the door to my parents’ downstairs closet and flicked on the fluorescent lights. The room smelled like old coats and disuse. There I was again, home for the holidays and indulging in some bi-annual sentimental scavenging. My broken beginner’s Fender Stratocaster was leaning against the wall; on the high shelf sat a retired edition of Trivial Pursuit, the name funnier than I remembered.

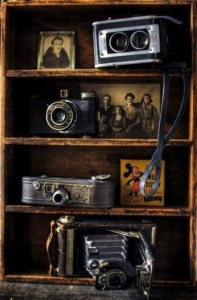

I lifted a cracked red photo album from one of the several stacks on the floor and leafed through its magic self-stick pages of 4 x 5s and their rarer, rounded 3 x 5 cousins. That mute memory book contained romance (my mother and father in mouse ears), politics (Israel with pre-1967 borders), even comic relief (my brother and I in matching Izod). Forgotten family trips, grandparents long departed, fashion’s cruel ebb and flow—I found more clues than clarification, more mystery than history.

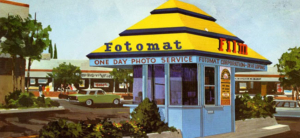

Crouched down on forty-year-old knees, I thought about how different things were in the analog age when gratification was more delayed. As a kid, I could point and shoot all I wanted but still had to hand the film off at Fotomat and wait for the results. When those colorful envelopes appeared—packed with possibility, their thick wads of doubles stuck together—my heart rate always increased.

Crouched down on forty-year-old knees, I thought about how different things were in the analog age when gratification was more delayed. As a kid, I could point and shoot all I wanted but still had to hand the film off at Fotomat and wait for the results. When those colorful envelopes appeared—packed with possibility, their thick wads of doubles stuck together—my heart rate always increased.

* * *

I don’t keep photographs anymore. The one of my mother smiling above my crib, her hair straight and shiny as Cher’s, is an anomaly. It is framed and hangs next to my computer, a reminder that once I was a baby, at the beginning of the journey. As a writer, I’ve come to rely more on my fractured mental inventory of images than anything else. Still, where did all my other photos go?

Some I lost over the course of many moves. Others I relinquished during breakup negotiations, or simply threw away. Between young adulthood and middle age, I got swept along by the post-millennial tide of disposability. This cultural mood, coupled with my predisposition for neurotic fits of decluttering, led to an increasingly scant, and finally non-existent photograph collection. I liked it that way, believing it made me tough and unattached.

Sometimes the weeding process itself felt freeing—like I could make past disasters disappear by disposing of the evidence. But not always. Once, while standing over the sink, I mutilated a picture of me with an estranged friend, struggling with the consistency of the cheap paper. As it turns out, trashing doesn’t equal transformation. Instead of destroying a memory, my tantrum only created a new one: me in the act of ruining.

Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Still #14, 1978

Nostalgia is hardwired to the technologies of our youth: whatever medium we grow up with tends to occupy a special place in our emotional memory. Photographic narcissism was once the exclusive realm of Andy Warhol and Cindy Sherman. Now we all document ourselves on the internet, posterizing the most minute twists and turns of our lives. But an online image is not the implicit equivalent of a photograph; photos have weight, maybe a soul.

The act of writing about a visual art (even one I enjoy as an amateur) is uncomfortable. Thinkers with far more authority on the subject have discussed the effects of digital photography on the form. In his essay “Gueorgui Pinkhassov” writer-photographer-historian Teju Cole writes, “What is the fate of art in the age of metastasized mechanical reproduction? These are cheap images; they are in fact less than cheap, for each image costs almost nothing.” I can’t answer his query, but I connect to the loss he describes. Since the late aughts, like most of us, I have become a master of self-portraiture, my greatest fear that a moment might pass unnoticed, unliked.

I’m all kinds of vain and enjoy snapping photos of my face, friends, flora, fauna. But I do so without thoughts of permanence. These orphan images exist entirely outside of the brick and mortar world. In the corners of Facebook, on old web pages, grinning from extinct social media platforms, there I am. At this rate, a Google deep dive will be my future version of flipping through a photo album. It’s hard to imagine feeling nostalgic about cached ghosts floating through cyberspace.

If someone performs a search of my name, they will find me with good hair, bad hair, black hair, and gray hair. They’ll see the performance and promotional stills taken in both flattering and poor light, in black and white and color. Sandwiched between these will be strangers with whom I share a first or last name.

Search results are public. But my missing photographs? No engine can make them reappear. There exists in my mind a catalog of lost snapshots. Each one is a small secret I share only with my past. What is it that makes certain images so indelible? And why do I continue to unearth newly remembered ones: delightful, embarrassing, invisible mementos of a splendid, stupid youth?

My date and I pose in front of our limousine on prom night: she, high on LSD, and me, with years of romantic suffering still awaiting me. (Polaroid, 1993)

I stand in a redwood forest at age fifteen, eyes closed, cradling a nylon string guitar, sun-lightened hair protruding from my tie-dyed bandana. (B&W, 1990)

On a bed in a San Francisco apartment, I wrap my arms around a dark-haired girl. I wear no shirt and have glassy eyes. The beard is one of my first full ones. (Polaroid, 1994)

Then there are the pictures untaken, experiences lost to time, that exist only in the unreliable and shifting expanse of memory. “Eating a Goat’s Gall Bladder in Kenya,” “Naked Hallucinogenic Beach Party,” “On Camelback in East Jerusalem at the Intercontinental Hotel,” “Late Night Co-Ed Anais Nin Book Club,” “Christmas Eve in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.” Missed moments, all. Never to be recreated, constantly evolving but never developed, these nonexistent pictures sit under perpetual formaldehyde. Dominance, balance, proportion and other aesthetic criteria remain subject to endless revision.

* * *

This is why I started to write about the past: to fill in the holes, flesh out the partially remembered dialogue, renovate my bygone life. Despite my earlier comments to the contrary, I’m no Luddite. I don’t resent the simplicity of shooting, uploading, and sharing. A life examined is a life examined whether the results of the inquiry appear on Tumblr, Instagram, or in an online literary journal like this one.

This is why I started to write about the past: to fill in the holes, flesh out the partially remembered dialogue, renovate my bygone life. Despite my earlier comments to the contrary, I’m no Luddite. I don’t resent the simplicity of shooting, uploading, and sharing. A life examined is a life examined whether the results of the inquiry appear on Tumblr, Instagram, or in an online literary journal like this one.

On a rainy Sunday afternoon last year, I climbed the rickety wooden ladder to the loft in the Seattle house where I lived. My plan was to spend a few hours writing, but I soon became distracted by an envelope my mother had sent months earlier which I had not yet opened.

I ripped open the neglected container and sat, transfixed by its contents: a 12th-grade graduation photo, receipts from my Bar Mitzvah party, high school transcripts. The sudden appearance of this miscellanea—most of which I did not recall ever seeing before—was jarring. The collection stirred in me a melancholy I hadn’t permitted myself to feel during my many years of studied austerity. I wasn’t so different from my parents with their closetful of albums after all. Seated cross-legged in the middle of those personal historical materials, I felt protective over my unexpected bounty. There was no way I was going to part with any of it.

Ari Rosenschein is a Seattle-based writer whose work appears in Stratus, The Observer, PopMatters, The Big Takeover, From Sac and elsewhere. Ari earned a BA in Theater Arts from UC Santa Cruz and recently completed the University of Washington’s nonfiction writing certificate program. He is currently working towards his MFA at Antioch University Los Angeles. A lifelong musician, Ari has released albums as a solo artist and as a member of The Royal Oui. He lives with his wife and their dog Arlo.

Ari Rosenschein is a Seattle-based writer whose work appears in Stratus, The Observer, PopMatters, The Big Takeover, From Sac and elsewhere. Ari earned a BA in Theater Arts from UC Santa Cruz and recently completed the University of Washington’s nonfiction writing certificate program. He is currently working towards his MFA at Antioch University Los Angeles. A lifelong musician, Ari has released albums as a solo artist and as a member of The Royal Oui. He lives with his wife and their dog Arlo.