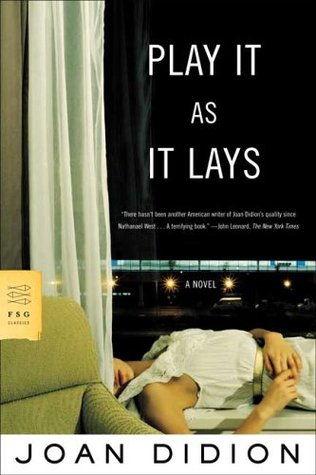

Writers Read: Play it As it Lays by Joan Didion

Play it As it Lays is the perfect novel and Maria is a fascinating mix between Lana Del Rey (the old Hollywood glamor, the detached gloom) and Little Edie Beale (the saltine tins, the psychic instability, the domestic disarray), appealing in large part because she is unapologetically herself. As Amy Schumer highlighted through a now-viral sketch, this is a rare trait among women.

Play it As it Lays is the perfect novel and Maria is a fascinating mix between Lana Del Rey (the old Hollywood glamor, the detached gloom) and Little Edie Beale (the saltine tins, the psychic instability, the domestic disarray), appealing in large part because she is unapologetically herself. As Amy Schumer highlighted through a now-viral sketch, this is a rare trait among women.

Maria renders glamorous so many traits of which I’m personally ashamed—she lives in her head, she loves sleeping in the afternoon, she craves mind-altering substances, she doesn’t want to talk to anyone (I, too, have trouble keeping up my end of the dialogue with hairdressers), she casually degrades her body, she lacks of patience for bullshit, she’s irreverent, all her friends are gay men or people with whom she is sleeping, she tends towards dysthymia, her body crackles with sensitivity, and she really just wants to spend her time wandering around and looking at the way the light hits random objects. These traits are glamorous in Maria because (a) Didion describes them beautifully (more on this later); and (b) Maria’s attitude—she is not embarrassed. I think her character is best captured in the following two passages:

“I try to live in the now and keep my eye on the hummingbird. I see no one I used to know, but then I’m not just crazy about a lot of people. I mean maybe I was holding all the aces, but what was the game?”

“For the rest of the time Maria was in Las Vegas she wore dark glasses. She did not decide to stay in Vegas: she only failed to leave. She spoke to no one. She did not gamble. She neither swam nor lay in the sun. She was there on some business but she could not seem to put her finger on what that business was.”

Maria renders glamorous so many traits of which I’m personally ashamed—she lives in her head, she loves sleeping in the afternoon, she craves mind-altering substances, she doesn’t want to talk to anyone…

I also relate to Maria’s nihilistic vision. We live in a highly competitive, status-conscious society—that is the game. I’ve often felt compelled to play the game, but Maria gives me permission not to. Maria sees through the bullshit and doesn’t apologize. She keeps playing because she has to to live, but she knows the game is ultimately meaningless. She instead finds solace in beautiful images, soothing her mind through sleep, wandering, and driving (also, through her fierce attachment to her daughter, Kate, the only relationship that matters to her). Her vision may seem depressing on its face, but there is actually something Zen about it. Maria doesn’t overthink things. Most people ask why Iago is evil. Maria doesn’t ask. Maria takes things as they are. She plays it as it lays.

Joan Didion

My second favorite thing about the novel is its classically California aesthetic, what I call Southern California Gothic. This is also embodied by the music of Lana Del Rey, who, like Maria, is interestingly not a native Californian. Both Del Rey and Maria solace on California highways. Note the similarities between between (a) Del Rey’s song “Ride” and (b) a passage from Didion’s novel:

a) “I drive fast /I am alone in the night /Been tryin’ hard not to get into trouble, but I /I’ve got a war in my mind /So, I just ride Just ride, I just ride, I just ride”

b) “Once she was on the freeway and had maneuvered her way to a fast lane she turned on the radio at high volume and she drove… She drove it as a riverman runs a river, every day more attuned to its currents, its deceptions, and just as a riverman feels the pull of the rapids in the lull between sleeping and waking, so Maria lay at night in the still of Beverly Hills and saw the great signs soar overhead at seventy miles an hour.”

California is a character in all of Didion’s writing, but Play it As it Lays presents a vision of California at its most haunting and glamorous.

California is a character in all of Didion’s writing, but Play it As it Lays presents a vision of California at its most haunting and glamorous. California is often romanticized as a paradisiacal dream land. Didion captures this allure, but beneath her prose lurks a more ominous reality. She does this by evoking the precarious California landscape and shining light on its residents’ insincere motives. An example of the former is when she explains that she sleeps outside in part because when inside, the “palms scraped against the screens.” I love the notion that palm trees—often considered a symbol of tropical paradise—for Maria are oppressive. An even more poignant example of the brutal California landscape is the following:

“Maria lay on the bed watching a television news film of a house about to slide into the Tujunga Wash. ‘I’m not living here, I’m just staying here.’

‘I still don’t get the joke.’

She kept her eyes on the screen. ‘Then don’t get it,’ she said at the exact instant the house splintered and fell.”

Here, Didion infuses mood into the scene through setting. The house sliding into the Tunjunga Wash helps drive home her dying relationship with Carter. The way Maria sees the world helps establish her character. She’s sensitive and soaks up her surroundings. She’s a careful observer. She views life from a distance, which is related to Didion’s cool, detached writing style. Didion’s sentences here are frosty and cinematic.

This is not the type of novel where I get lost in the narrative. This is the type of novel where I want to sit with every sentence for minutes or hours or days or forever

This is not the type of novel where I get lost in the narrative. This is the type of novel where I want to sit with every sentence for minutes or hours or days or forever. I’ve probably read it ten times now and every time I come across a new sentence or passage that overwhelms me. This time around, it was the following:

“What happened was this: I looked all right (I’m not telling you I was blessed or cursed, I’m telling a fact, I know it from all the pictures) and somebody photographed me and before long I was getting $100 an hour from the agencies and $50 from the magazines which in those days was not bad and I knew a lot of Southerners and faggots and rich boys and that was how I spent my days and nights.”

I’m in love with this sentence. It packs in immense detail and is very long but still easy to read. It establishes character. Most beautiful women apologize for their beauty or are uncomfortable with it (the patriarchy forces this upon them), but Maria states her attractiveness as an objective fact. I also like the combination of “Southerners and faggots and rich boys.” Maria has an army of men at her behest and its part of what makes her such an icon.

Sometimes I see this book less as a novel and more as a series of beautiful poems/vignettes about the coolest woman in the world. Either way, I think it’s perfect.

Anna Dorn is an attorney and writer living in Los Angeles. She regularly writes about music for The Hundreds and DJBooth and legal issues for Justia. In the past, she has written for Thought Catalogue, Labeling Men, and Vice Magazine. Her article on juvenile life without parole was recently published in American University Law Review.

Anna Dorn is an attorney and writer living in Los Angeles. She regularly writes about music for The Hundreds and DJBooth and legal issues for Justia. In the past, she has written for Thought Catalogue, Labeling Men, and Vice Magazine. Her article on juvenile life without parole was recently published in American University Law Review.

Anna holds a BA in American Studies and Creative Writing from UNC-Chapel Hill and a JD from UC Berkeley Law School. She is in the process of getting her MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University in Los Angeles.