Poetry For Prose

“Everywhere I go I find a poet has been there before me.” – Sigmund Freud

I find myself drawn to the writing of poets-turned-novelists, or poets-turned-memoirists. Michael Ondaatje, long before he wrote The English Patient or any of his other novels, was a poet, as one might glean from his prose. Who but a poet would write, as Ondaatje does in In The Skin of A Lion, “Everyone has to scratch on walls somewhere or they go crazy”? The poet donning the hat of a prose writer never loses the lessons of poetry when he switches genres. The poet-mind, once inhabited, may never be shed. It compels the writer to notice the world more vividly, to seek out the power in the moment, and to inhabit the visceral.

* * *

Hear, O Israel, my disembodied home,

my surrogate hovel, my dusty cavern:

I never slipped inside your insidious

borders, bobbed to your techno beat,

slithered into your dead lukewarm waters.

* * *

To a writer of personal essays, the leap to poetry is a small one— perhaps more of a hop across a small puddle, a gleeful romp in the rain than a leap—because the subject of poems and personal essays is the same: me. Implicit in both forms is the overarching I, or should I say eye, of the narrative. Here is the wide-eyed narrator, allowing the reader a glimpse into the recesses of his mind. There are minute details—the seemingly innocuous lilt of a lover’s voice, the ominous rustle of a fig tree in August—that are given witness. Above all, the poetic form gives the memoirist license to approach his memories in whatever manner he wishes.

* * *

My father’s tassels snipped off

before he was born so I had nothing

to cling to on the long journey west,

my hands buzzed like gnats

at his sides but The Lord never

granted me fingers for grasping.

* * *

Poets, through practice and reading, learn techniques that help us snag a reader’s attention. We learn about the aesthetic power of words. We learn to use language boldly and economically. We learn that a narrative is not panacea. Above all, we learn to ground our writing in the concrete. We revel in the power of the image. The best poems are those that give readers something to bite into, those that appeal to the senses. We learn to be intentional with our word choices. And perhaps counter-intuitively, we learn how freeing it is to work within a structural framework, and how structures might engender specific feelings or themes. Anyone who’s ever written a sestina understands its inherent meditative, almost obsessive qualities. Or the beautiful, dense, natural rhythm of the haiku. Working within form often acts as a distraction from the subject of the writing, which, paradoxically, helps it along.

* * *

I forgot the commandments:

they sank into cool, clear lakes far away

from Israel, the cold does not bear

the arid adjectives of The Chosen.

The Lord changed his mind about me.

* * *

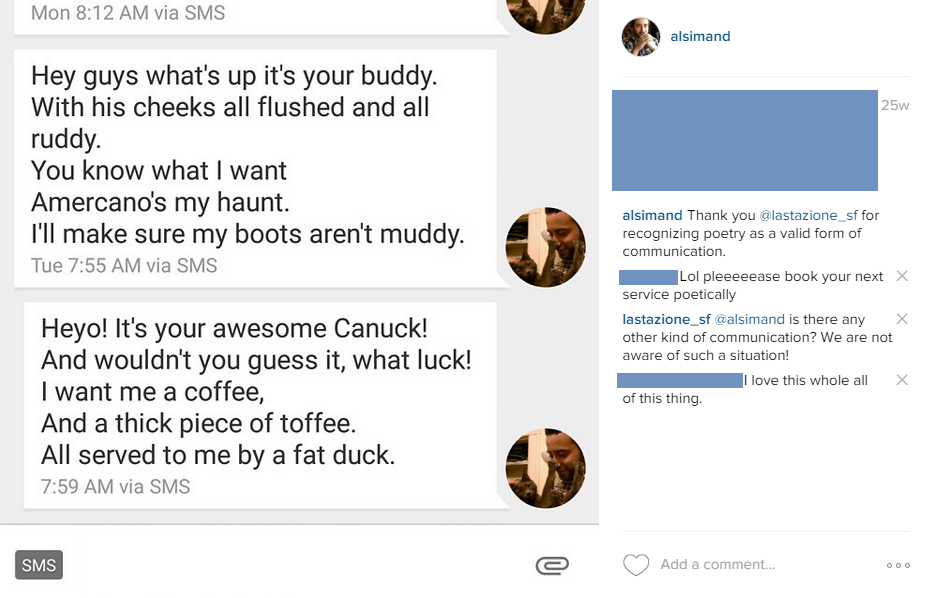

If asked at a party, provided that I am sufficiently inebriated, I’ll admit I am a poet. Maybe I’ll recite some T.S. Eliot. Or I would if I could ever commit his words to memory. Yes, I am a poet: beret-clad, scarf-wrapped, eyes half-closed poet. I swim in metaphor. I gobble up alliteration. Enjambment arouses me sexually. I have even convinced my local coffee shop, which accepts coffee orders via text message, to accept my orders in limerick:

* * *

Hear, O Israel, my faded dream,

my slippery landscape, the burning bush

that scorched my brows, my lashes.

I am exposed before you to pointed fingers,

on my knees before the Wailing Wall,

my confessions, breathed, slipped

like smuggled diamonds into its cracks.

* * *

Granted, the I in the poem is a vastly different I from the personal essay. The poetic I is a persona, a mask donned for the purpose of inhabiting a particular perspective or living a particular emotion. The I of the personal essay is expected to be true. The narrator is expected to be reliable. And though the bounds of truth in nonfiction are hotly debated, most writers would agree that, in memoir, the reader has certain expectations of the narrator: that they will, to the best of their ability, describe events as they were. This is not always the case in fiction or poetry.

* * *

You see—I’ve whored, I’ve been whoring,

my atonement crumbles like an old mural,

the throats of San Francisco denizens

calling you fascist while I nod my head,

these words that squeeze my heart

when I walk by the wayside,

go by the wayside, too tentative

to extoll your hollowed name.

* * *

Writing poetry is an exercise in shedding constraints. It is a Houdini act. You pick the padlocks of form, loose the shackles of narrative, and tear away the straitjacket of the sentence. When you burst from the fraught waters of prose, you are naked and free to daydream. You are no longer worried about what it all means. You simply allow your subconscious to speak. You allow yourself to play with words and hold sounds in your mouth like oversized jawbreakers. Non-sequitur? No problem. Mismatched adjective? Unlikely verb? Please do! Feel like giving silence a persona, to give him a seat at the table beside your mother and father? Sounds great!

* * *

Hear, O Israel: I have nothing to teach

my unborn children except how to lose

ones way, how to lie down in the street

and let the mind grow gray. They will

never wear frontlets under their caps,

stoop and sway and subjugate themselves.

Their doorposts will read Bay Alarm.

They will not need rain:

we have the technology to overcome

Your droughts, reservoirs on Mount Sinai

so they will never have to carry water,

their lips never chapped, never uttering

Your Name, Your Love, Your Spite.

* * *

The poem gives the personal essayist license to hold an event—or a person, or a place—in her hand, to find its form, to feel the beat of its heart. She can dig it up from the depths of memory and place it in a jar with tiny air holes stabbed into the lid. A firefly perched upon the windowsill. She might gaze upon it or feel its heat when she places her hands around it. Often, a writer’s intent when beginning a personal essay isn’t known to her. It’s only after months of writing, of many tortuous edits and rewrites, that she discovers a fertile seed from which the true essence of the essay will spring. The human psyche is dark and complex, and it will not often give its gifts willfully. The poem is a shortcut of sorts to this delicious morsel. It is a truffle pig whose nose thrusts dutifully into the peat of your secrets.

The poem gives the personal essayist license to hold an event—or a person, or a place—in her hand, to find its form, to feel the beat of its heart. She can dig it up from the depths of memory and place it in a jar with tiny air holes stabbed into the lid. A firefly perched upon the windowsill. She might gaze upon it or feel its heat when she places her hands around it. Often, a writer’s intent when beginning a personal essay isn’t known to her. It’s only after months of writing, of many tortuous edits and rewrites, that she discovers a fertile seed from which the true essence of the essay will spring. The human psyche is dark and complex, and it will not often give its gifts willfully. The poem is a shortcut of sorts to this delicious morsel. It is a truffle pig whose nose thrusts dutifully into the peat of your secrets.

* * *

Hear, O Israel, you dark-skinned beauty,

your bare shoulders your round breasts

haunting the lust in my heart.

They say about your women,

they are fiery, the heat between their legs

angry, inviting, always looking to barter.

* * *

I recently caught up with a classmate. We met at the side of a lake in Oakland and watched as runners sped by, their dogs in tow. My classmate is a poet turned prose writer. When I switched to poetry, they switched to nonfiction. We met in the middle and compared notes. A year earlier, we had encouraged each other to make the switch. As we sat by the lake, and I pulled out a book, Nick Flynn’s The Reenactments, they said to me, “Oh man. I knew he was a poet before he ever admitted to it.” The Reenactments is ostensibly Nick Flynn’s account of the making of a movie, Being Flynn, based on his previous memoir, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City. Really, it is an emotional reliving of trauma as he watches it unfold in movie form. It is a meandering meditation on the movies we play in our heads. It is a dense collection of poetic truth. Nick Flynn had created his own form. I nodded my head in agreement to what my friend had said. “Totally a poet,” I said.

* * *

O Israel, grant me access to your brothel,

let me drink your salty waters,

let me taste the green-eyed goddess

who walks your shores, the tidal surge,

the emerald of their eyes piercing

like Moses’ booming voice, choking

the weak protest from my trachea.

* * *

I believe all prose writers, fiction, nonfiction, or miscellaneous, can benefit from the practice of writing poetry. Every morning when I wake up I jot a few words into my dream journal—I don’t dream lucidly: I only call it my dream journal so that it might jump-start my subconscious. In those moments, scribbling words in a state of half-sleep, I feel connected to myself in a way my waking self is not. When I sit on my bed, notebook teetering from my fingertips, what I produce feels simultaneously foreign and profoundly personal. This is precisely the mind state in which a poet means to dwell when he writes, and the very same litheness from which I benefit as a prose writer.

* * *

Hear, O Israel, my birthright reneged,

my disappointed peer going tsk tsk tsk

at the ink that surges through my veins.

You will bury me one Sabbath morning

and I will walk the dusty path to your gates

scrawled with hieroglyphs, with barcodes,

with torches and pitchforks and blood-

stained broadswords, the Maccabees hiding

in the mountain pass beyond your borders.

You will not begrudge me your entry

for the Lord’s anger was kindled but, I hope,

my father forgot to stoke the flame.

* * *

Poetry in this blog post has been extracted from Hear, O Israel, which originally appeared in Drunk Monkeys.

Alex Simand is a MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. He writes fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. His work has appeared in such journals as Red Fez, Mudseason Review, Five2One Magazine, Drunk Monkeys, and others. Alex is the current Blog Editor for Lunch Ticket and past Editor of Creative Nonfiction and Diana Woods Memorial Prize. Find him online at www.alexsimand.com or on Twitter: @AlexSimand.