Say My Name, Say My Name

Years ago, when I first met the girls who are now my stepdaughters, and when we were still getting used to each other’s company, I invited them to call me by the nickname my family has always used: Ari. “Arielle” felt a little cumbersome for five-year-old Shiloh’s lisp, and too formal for nine-year-old Rose’s warm welcome. It was the holiday season, just after Thanksgiving. I had been dating their dad since the summer, but we’d wanted to know we were a sure thing before getting the kids involved. Now, the girls, their dad, and I were driving out to the Los Angeles Arboretum for a drizzly afternoon walk through the trees, and our first outing all together.

“Ari. Arrrrriiiiii. Ari, Ari.” The girls both tried out my new name, bouncing it between each other, rolling it over their tongues. Rose twisted it into a lyrical phrase. She sing-songed my name as the gray day slid past the car windows, her eyes the same as the sky.

Little Shiloh, in her pink princess car seat, new to the written word and steeping in Seussisms, stretched my name through phonics and blended it into rhymes.

“Ari. Bari, gari, tari. Artie, marty, farty,” (giggles from the backseat), “artie, artAY, parTAY…” Shiloh babbled on and my nickname swayed and morphed as the girls got comfortable with it, and with me.

As we pulled into the Arboretum parking lot, the girls settled on a chant—“ArtAY, ArtAY, ArtAY likes to parTAY.” We all sang as we stuffed clementines and water bottles into a backpack, skipping off to see the peacocks. By the time we drove home a few hours later, weary and hungry for dinner, I had been renamed. From that day on, I was Artá. (Of course the spelling, with the accent, came later.)

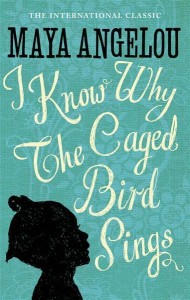

I recently read Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. This was my first reading of the memoir, and while my fingers are crossed that your repertoire is better, in the event you haven’t read it, I’ll give you this: it is a coming-of-age story that explores, among other themes, self-identity and personal dignity in a racist and male-dominated world.

I remembered the day my stepdaughters named me Artá while reading through Chapter 16. In this chapter, Angelou is ten years old. Her family “had owned the only Negro general merchandise store since the turn of the century.” Although they were one of the wealthiest in her Alabama town, for a short while she worked for a white woman, Mrs. Cullinan, to learn “the finer touches around the home, like setting a table with real silver.”

Angelou’s mentor at the Cullinan’s house was Miss Glory, a cook whose family had worked for the Cullinans since their days in slavery. Miss Glory’s mother-given name was Hallelujah, but Mrs. Cullinan renamed her Glory. Likewise, Mrs. Cullinan refused to call Angelou by her given name Marguerite. “That’s too long,” Mrs. Cullinan said. “She’s Mary from now on.”

As writers, we communicate a great deal to our readers by the names our characters give each other. What they call each other speaks volumes about their relationships. Mrs. Cullinan’s character and values were revealed by Angelou’s anecdote about the names. In Chapter 16 she showed, perhaps especially to those of us who primarily write creative nonfiction, how we can deepen a reader’s insight into a story by the way our characters are named by us and how they name each other.

When Shiloh and Rose named me Artá on a cloudy day all those years ago, they indicated their insight that I was going to be close in their lives, and that they welcomed me in. By accepting my name of their choosing, I indicated my respect for them, my willingness to let them call some shots in an otherwise adult-driven world.

Names—particularly, giving a name to someone—is a powerful thing. It indicates ownership: mothers name their children; lovers name their sweethearts; children name their dolls. When Mrs. Cullinan renamed Hallelujah “Miss Glory,” she proclaimed her undisputed hierarchy. When she renamed Marguerite “Mary,” she did so to insult and disregard Angelou’s self-identity. When the girls named me, they indicated—perhaps subconsciously—that they affectionately welcomed me into their world.

As Maya Angelou said, “We belong someplace. The day we are given a name we are also given a place which no one but we can fill.”