Separated Faces (A Year in Baltimore)

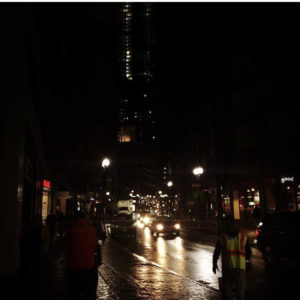

My mother opens her eyes to a vast cloud of nothingness. Freckles of light poked through the edges of the roof piercing the blended darkness. This was her sixth month living in Baltimore alone and winter was in full swing. Some nights she could see her breath. She wished she hadn’t underestimated the lack of insulation and how cold Maryland got, back when she first decided to rent the place in the summer of 2002.

My mother opens her eyes to a vast cloud of nothingness. Freckles of light poked through the edges of the roof piercing the blended darkness. This was her sixth month living in Baltimore alone and winter was in full swing. Some nights she could see her breath. She wished she hadn’t underestimated the lack of insulation and how cold Maryland got, back when she first decided to rent the place in the summer of 2002.

This is my mother’s third time waking up tonight. Her bladder aches begging to be relieved as she pulls the blankets over her head and shudders. She figures her building hasn’t been renovated since its construction in the 20s. She occupies the unfurnished attic on Charles Street for only $400 dollars a month near the John Hopkins campus. Her mattress lays on the floor. Her clothes are neatly stacked inside the luggage bags she’d brought with her when she flew up over the summer. She rents from a coworker at the cabinetry company. The man had become a father right around the time my mother needed a place to say.

The baby sleeps downstairs in the room next to the only bathroom in the residence. My mother squirmes the pee dance from her bed, her elbows and knees sharp in the sheets. This is month six now, and she only weighs 94 pounds. The stair’s creak and the flushing noise would be more than enough to wake the baby and make everybody else miserable for the rest of the night, so she holds it in, the way she does most nights.

The three year anniversary of my mother’s immigration to the US passed back in October.

* * *

I am about nine years old around this time. My brother is seven. My mom calls us on the anniversary of our move, reminding us of what was now considered a holiday in our family. Over time this day grew ominous, like the anniversary of someone’s death.

Our immigration was the result of the instability in Colombia at the turn of the century and my parent’s separation and consequent divorce. There were alleged infidelities and my father’s refusal to leave the country he’d lived in his entire life. After separating from my father, my mom came to the States on a student-visa. She brought my brother and me along to Florida where she studied at a community college.

When that ran out, she was faced with needing to get a job if she wanted to stay in the country. Once in Florida, my mother had nothing left back home. No reasons to live in the past. Moving had given us the ability to hope because all we could think about was the future. That alone was a good enough reason to risk our livelihoods. That winter a 200 kg bombing killed 36 people at El Nogal, back in in Bogotá. Two hundred people mangled by the car bomb. Sometimes when my mother woke up and found herself isolated in the attic, she remembered being held at gunpoint with my brother and me right before we moved. Going back to Colombia was not an option, especially as a single mother.

My mother scrambled to get a job. She tried everywhere, but had no luck. It needed to be an employer willing to help with our immigration process and sponsor her green card. My mother, then in her early thirties, had no job experience and barely knew any English. Her undergraduate degree in administration was ten years old now and earned in a country nobody here seemed to care about.

She met the owner of a cabinetry shop at a party and quickly told him about her plight. A second cousin, the only type of people she knew here, had invited her. She’d spent the night telling everybody who’d listen about her situation. The man, a Baltimore native and strict Ravens fan, offered her a job. He asked her to move up to to Maryland and work for him in an administrative capacity. He couldn’t offer her a lot of money but it was something. My mother said thanks but that she wouldn’t be able to bring my brother and me with her under the circumstances. She’d been living off her savings and child support payments from my father back in Colombia.

The man said that it was the only way he could help her. That maybe after some time she could return back to Florida and be with my brother and me again. It was either that or go to some place that wasn’t home any more.

My mother left us with my grandmother in Orlando and lived out of her suitcase in the creaky attic, calling us every night.

* * *

From the first day she knew what he wanted. “Why else would he hire me? I didn’t even know English,” she says now. The man routinely asked her out on dates, even at work. He bought her necklaces and gave her rings.

My mother told my brother and me that eventually she’d be able to work in Florida, but we quickly realized that instead of offering us a way to stay in this country, the man was dangling broken pieces of hope. My mother called my father and asked if we could all come back to Colombia. The answer was always no and she soldiered on. There was no one else to report this to. Her harasser wasn’t only her boss—he was also the only man keeping her and her kids in this country. My mother went to bed every night in her attic thinking he’d change his mind. She’d warned us over the phone to be ready to go back in case the moment ever came.

My mother told my brother and me that eventually she’d be able to work in Florida, but we quickly realized that instead of offering us a way to stay in this country, the man was dangling broken pieces of hope. My mother called my father and asked if we could all come back to Colombia. The answer was always no and she soldiered on. There was no one else to report this to. Her harasser wasn’t only her boss—he was also the only man keeping her and her kids in this country. My mother went to bed every night in her attic thinking he’d change his mind. She’d warned us over the phone to be ready to go back in case the moment ever came.

Another local Baltimore business man, let’s call him Bill, noticed my mother around this time. Bill worked in an electric company that was somehow affiliated with her cabinetry shop. He asked her out to dinner, which my mom was happy to say yes to. It was was one of the first positive nights she had since leaving Colombia.

When her boss found out, he waited for her at his desk the next day. “He was furious,” my mother says. He asked her how she could see someone else when she knew he wanted her. Her boss picked up the phone and called Bill in front of her.

My mother realized that there was only one way to get back to Florida. She, a Catholic woman who’d never been with anybody except for my father, slept with her harasser. The next morning he gave her permission to come back to her kids. He said she could work from Florida and he’d still sponsor her. My mother tells me this for the first time as we discuss this piece. “I never told anybody anything. You can write what you want. I did it for you,” she says.

I hang up afterwards, trying to wear the poker face of a journalist in a war zone. I postpone thinking about until I have to for the ending of this piece.

* * *

My cousins told me that if you forgot the way someone looked, it meant you didn’t love them anymore. Some nights or when I daydreamed in school, I would etch my mother’s face in my mind a million times.

I thought I knew a lot for a nine year old. It was the first birthday I spent fatherless, but my grandparents did everything to help me forget. As a little kid I learned to act calm and to compartmentalize whenever I had to in front of my little brother.

One time my mother flew into Orlando for a weekend and surprised us at school. Leaving school early never felt so good.

There was another time when we went to go get her at the airport for a different visit. The Orlando terminals are filled with theme-park related gift stores. There’s a NASA one too. My brother and I waited in the back of the Disney store, playing with some toys. I turned around and saw a brown-haired woman standing with her arms folded, staring at us. I noticed her silver necklace, one she’d had brought from Colombia, and then her eyes, realizing that that woman was my mom. I remembered my cousin’s words and froze, showing no emotions at all. A wave of guilt submerged me as I thought I’d done something terrible. It’s the image I think about the most often when I see separated immigrants reunited down at the border by Mexico. I wonder if some of these kids feel that—not recognizing anything at all.

* * *

In 2008, five years after coming back to Florida, my family was granted Residency status. My mother was now legally and financially able to say no. When her boss mailed her his next gift, she returned it and was told she needed to find a new job that day. My mother gained her US citizenship in 2013, ten years after living in the attic.

We stopped living together when I left Florida for Boston. Then I found myself further away after I unpacked in LA. Looking back my mother blames my father for everything that happened during her year in Baltimore.

I pause before saying, “Mami, I don’t think so.” I tell her I think her harasser took advantage of her.

My mother sighs. “I know,” she says.

* * *

Most of us have seen the recordings and read the news of the family separations at the border this year. Almost 2,000 kids were separated from their parents between April and May alone. In some cases the government even deported parents while shipping their children across the country, making it almost impossible to reunite them.

There is a lot of outrage. You are probably outraged.

But, if we were willing to tolerate the legal immigration system that allowed, and continues to permit, the exploitation of the most desperate people, how can we be so surprised? I am not saying that what happened to me is even close to the human rights abuses at the border. But our notion that immigrants are somehow less human has always been expressed by Americans in power.

According to the ACLU, 25 to 85 percent of working women have experienced sexual harassment, with immigrants and low earning workers being the most vulnerable. The ACLU also notes a 2009 survey of Iowa meatpacking workers where 91 percent responded that immigrant women do not report sexual harassment or sexual violence in their workplace.

Not only is there an imbalance of power, but their inexperience with the American legal system impede their ability to seek representation or speak out against these violations.

Our government is not making policy up from thin air. It has been given permission to act and abuse the way it does by a culture that has always done the same thing.

* * *

It’s been a few days now since my mother and I spoke about Baltimore. It was close to impossible for me to have a reaction to the truth my mother’s choosing to reveal only now. The only thing I can feel in regards to my immigration story and my mother’s sacrifices is a sense of pride and invincibility. Feeling anything else is like committing some form of treason or betrayal.

I didn’t think about what my mother said until a few days later when I debated on where to get a new tattoo. When I pictured it on my body I thought about how sad my mom had gotten when I first permanently inked my skin.

I thought about my mother’s year in Baltimore and realized that I had to hold myself to some different set of traditional standards. Guilt greets me for leaving home, never coming back for anything (including when my mom got sick last year), and not going into law school or something like my parents had always wanted. No more tattoos. Nothing tainting my body or my future like my mother intended when she sacrificed so much for me. But then, in doing so, I would be losing some part of who I am and my pursuit of happiness and self-fulfillment.

Would changing who I am mean that my mom gave those parts of me away in her sacrifice? I know that was not her intention, but I won’t always know which way to go.

Esteban Cajigas is a writer, musician, and MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. His short stories and poems have been featured in publications such as Venture Magazine, Foliate Oak, and others. Esteban also previously wrote for The Boston Globe as a correspondent and The Suffolk Voice as Editor-in-Chief. He lives in Los Angeles with his mischievous cat, Zelda.

Esteban Cajigas is a writer, musician, and MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. His short stories and poems have been featured in publications such as Venture Magazine, Foliate Oak, and others. Esteban also previously wrote for The Boston Globe as a correspondent and The Suffolk Voice as Editor-in-Chief. He lives in Los Angeles with his mischievous cat, Zelda.