The Mind, The Body, The Voice

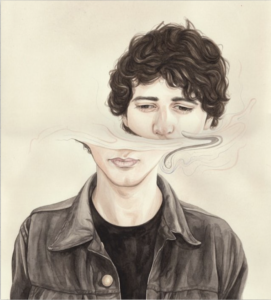

Polo by Henrietta Harris

When asked, I almost always give up and offer the term “a nonsexual orgy.” People enter a dance studio in a leafy Boston suburb and commence to touch, play, and move with each other’s bodies. What else should I call it? The people who come here often know it by its technical name: A Contact Improv Workshop. The people who come here often are easy to spot—their bodies are animations of loose legs, arching arms, and torsos that tilt from side to side, like the middle of question mark, inviting newcomers to join their dance. On their faces is jubilation, for they have achieved utter freedom. David is one such person. To the soundtrack of elongated sighs, gentle movement suggestions, and the soft polyrhythm of mbira melodies, we met the way a shining boy picks a wallflower from a garden wall.

At the time, I was a marriage and family therapist in training. My days were spent seeing others in pain, while never being seen in my own. Contact classes offered a reprieve from speaking, thinking, analyzing—my only instruction was to let my body feel and connect to the multitude of energies in the room. Even though I was not a particularly adventurous participant (I seldom partook in the running, leaping, and partner-lifting activities), I was at peace with my presence in that space, no matter how little real estate I took up in the room. I didn’t expect any attention or engagement from a more seasoned mover like David, and so surprise nipped me when I felt his back meld into my own. That one movement began a dance in Boston that would continue in Southern California, weeks and months later.

Maxi by Henrietta Harris

On Thursday nights in Santa Monica, David hosts contact improv playshops much like the event where we met, only more saturated with his personal brand of liberation. We all lay out across the floor, like twigs in a pond, listening to the tenor of his voice. “I want you to imagine that you are a baby animal and that you’ve just entered the world,” he says over a friendly microphone to a group of 20 participants in a local arts center. “Explore your body,” he suggests. “Explore your limbs. How do they work? What do they do?” We internalize his instruction and move like the creatures we have each envisioned. “Make whatever perfect beautiful sound your baby animal makes!” A smorgasbord of sound resonated through the space as participant voices imagined and emulated their baby animal sounds. I was perhaps the only one who didn’t make a sound. No one seemed to notice, which inducted me into an experience of feeling muted and invisible. Why was I unable to make a sound?

A participant leaped past me, arms outstretched. They let their voice trill out like a bird call. Other participants joined in. By this moment, we had shed our animal personas and were free to move and vocalize about the space as we pleased. I watched, as pleasure ran across faces, like rainwater running free down a windowpane. Everyone seemed to unleash their joyful noise. But there was a muzzle over my mouth, as though my thoughts and feelings were only able to leave me if they fit through the openings between the bars. In childhood, I sang, screamed and spoke when I wanted to. If I were still a child, I could have engaged in this creative space with ease. Why now was I so distanced from it? Why did I feel so paralyzed by it? “Do you ever stop talking?” An uncle once mocked me. Discovering my pain is like finding a stern knot in a thread I don’t remember making. I found a wall to lean on for support and took snapshots in my mind of David’s class as it spun on without me. When was the last time I heard my own voice?

Tild by Henrietta Harris

In fact, it was a year earlier on a trip to South America, a place I’d never desired to go, when I last heard myself. From the moment I stepped off the plane in Peru, I was enamored. Maybe that was my voice, buried deep inside, that bubbled up to inform me of my unexpected excitement. I was there as an addendum to my therapist’s training, scheduled to volunteer as a clinician at an orphanage in Cusco. It was there a small girl was assigned to me: Alicia, a six-year-old who experienced severe cognitive and linguistic impairments. In retrospect, it is not so surprising that I connected to her. To others, her voice was lost, too. Unable to grasp language or speak it, Alicia’s only way to express pain was to slap her own face and scratch her skin raw. Instead, when she verbalized, her words were her own, hers only to understand. Could something like that be enough for me? I wondered. Even if no one else understood me, could I be satisfied if I alone understood myself? Despite a lack of language, despite her life in an orphanage where the childrens’ beds doubled as cages, despite her abandonment by family members who could not support her developmental challenges, Alicia’s singing could sway the ocean. Her laughter could light the night sky. In only a few short days, I felt like I belonged with her, something a therapist is not supposed to feel. It must’ve been my voice that named that deep tugging at my heart as universal unconditional love.

On a Monday night not too long ago, David shared with me that he’d similarly experienced such profound love. Where my dance with it originated from a trip to Peru, his originated from a trip to the home of a local shaman to participate in two South American spiritual healing ceremonies. He spent the weekend on a journey with ayahuasca and huachuma, psychedelic spirit drinks developed by the Mayans to awaken and grow our unconscious minds. I was not well-versed in the world of psychedelics or indigenous medicines, but clearly, as he utilized his hands to better explain it to me, David was.

Bryce Commission by Henrietta Harris

“Ayahuasca is thought of as the mother; she opens the experience and teaches you things,” he illustrates. “Huachuma is thought of as the father, who helps you integrate the things you’ve learned and closes the experience.” David detailed his experience for me; he went to a shaman’s home, along with other participants in the ceremony, drinking ayahuasca around nine in the evening and staying up overnight, under the caring watch of the shaman. While his body processed the ayahuasca in his system, he saw visions. He was able to link his childhood to the trauma he’d managed his whole life. This discovery was transformative, but secondary to his experience while participating in the huachuma ceremony: While under its influence, he experienced for the first time an embodied sense of universal unconditional love. All of his resistance fell away. He felt at once connected and disconnected from the world. He loved himself and everything around him more than he ever had before. While on huachuma, he found himself capable of doing so.

He hoped such a powerful experience would stay with him. “I wonder if the effects will last,” he mused. I wondered too. I had almost forgotten about my own experience with universal unconditional love.

Opportunities for self-fulfillment are like ornate doors of iron or marble. They open the way for gratification, but their weight makes it impossible for them to stand open for too long, which begs the question: Can self-fulfillment be long lasting? Or must we experience it on a morsel-by-morsel basis across the countless moments of our lives?

It was in my wondering that my voice came to mind again. At once I began to feel myself being drawn apart by the draw of David’s knowledge and experience. Part of me was deeply moved by the softness and authenticity radiating from every inch of him. His profound compassion and gentle confidence touched me. His eyes were hypnotic, rich and soulful. He was powerfully humble and powerfully alluring. He was at once a business expert, a dedicated community organizer, and a spiritual monument. He was a leader in his community, where he invited people into the healing practices he identifies with. He was a white man who appears very seriously and deeply connected to culture and heritage beyond that of his personal contexts. He was deeply attractive, inside and out.

In that conversation with him on a June gloom afternoon, outside the Santa Monica co-op, sudden sunlight fading back like a wave’s retreat, I realized that David Rhein was free. His mind was free, his body was free, and perhaps most mesmerizing to me, his voice was free. And for several moments, I almost wanted his voice to be mine. I almost wanted him to speak for me and shape my connection to the world around me. I almost wanted his philosophy to wrap me up like a shivering child, like the child I was when someone told me to stop talking so long ago. I discovered that afternoon that while in the company of David Rhein, I want to give up on doing the imperative, heart-wrenching healing I’m meant to do and melt into him instead. Why work to find my truth when his is so beautiful, so deep, so fulfilling? His balance, his pleasure, his peace seem so big that they almost appear enough for two.

Your Tomorrow by Henrietta Harris

The afternoon swept into evening. He and I met that day so that I could attend a party at his home. In only an hour, I found myself in his house, alone amidst his buzzing open-minded friends and community members. Everyone knew each other. Everyone was connected to one another, to the energy of the space, but I again felt as I had in David’s playshop, muted and invisible. Only one thing was different—in David’s class, my loneliness lead me to myself, to the self-exploration and healing I need. At David’s party, my loneliness lead me to him. My eyes followed him around the room, my skin called for his. I felt myself yearning for our first dance, back to back, where I stood so close to his free spirit that I, too, almost felt free.

It was my voice that understood. This place was a danger to it, to my personal growth. It could sense that if I didn’t resist David’s gravitational pull then and there, perhaps I’d never resist it. Perhaps I’d give in and give up, closing myself off from the personal work I have always been meant to do. It knew that if I did that, I would never hear my own voice so clearly or profoundly as I heard a wingless child sing. I would never discover my perfect animal sound or fly free through air in my dance with life. And so I left the party, and I left David. Even if I couldn’t yet use my voice, I could attempt something equally important: Listening to it.

Regan Humphrey is an award-winning writer and MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles, studying Young Adult Fiction. She is the author of What A Heart Loves, a five-act Elizabethan play written in iambic pentameter, which made its first theatrical run at Saint James Place in Western Massachusetts. She is a published author and poet and served as an Editor-In-Chief for Whole Terrain. She is a writing mentor, film-enthusiast, music-buff, and longtime performer. She holds degrees in Marriage & Family Therapy, Cross-Cultural Relations, and Creative Arts, Writing & Performance.

View the featured painting series by Henrietta Harris at henriettaharris.com