The Old Folks’ Home

No matter how smart or self-sufficient you are, the day may come when someone else takes care of you. Someone will give you medicine, drive you to doctors’ appointments, take control of your finances, and change the batteries in your hearing aids.

My husband is older than I am. I tell him, “Honey, you’ll never have to hire someone to push your wheelchair and change your diapers. You have me.”

“That’s sweet,” he says.

“I’ll hire someone to do all that,” I say, and then I have a good laugh.

Hilarious as that old joke is (to me, anyway), it’s not untrue. If we’re lucky to live long enough to become feeble, we’ll need someone to deal with our decay and decrepitude.

In the old days, when extended families kept their old folks at home, they may have been neglected, abused, and had their social security checks pilfered, but by people who loved them or had history with them and a sense of familial obligation. In assisted living, you’re at the mercy of strangers. On the other hand, depending on how you treated your family when you were of sound body and mind, or how difficult you are in your dotage, you may prefer to be cared for by strangers who don’t know that your cantankerous, foul-mouthed, and demanding ways are not a product of old age. Rather, these traits are the real you, sans the filter of giving-a-fuck. And taking care of old people is hard work. It requires preternatural patience. It’s like taking care of a one-year-old but without the cuteness. For these reasons, plus many others, assisted living facilities, bad as most are, are a necessary evil.

In November of 2021, I moved Mama from her house in Georgia to California after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. I tried to settle her in an assisted living place, Ocean Breezes in Santa Monica, close to my house. The “senior apartments” had views of beautiful sunsets over the Pacific, and you could hear the sound of waves crashing late at night when the traffic eased. Mama reminded me she couldn’t see or hear anyway when, after just two months, she broke the news that she wanted to leave Ocean Breezes and go back home—to Georgia.

I’d gone to considerable trouble and expense and devoted three months of my life to moving her closer. I was sad I wouldn’t have her close by anymore and then angry because all my effort had been for nothing. I felt like I had a sweat-equity interest in keeping her in California, but seeing her so unhappy undid me. She hated the food at Ocean Breezes. She insisted you could only get decent fish in Georgia. I told her she was probably the only person in the history of fish eating that had ever uttered those words. She said the staff didn’t wash her linens often enough and that someone was stealing her underpants. She caught COVID there. Thankfully, fully vaxxed and boosted, her case was relatively mild.

Truth be told, the place was awful. Like most assisted living places (I like to call them “Ass Livings”) they overpromise and under-deliver. Ocean Breezes was criminally understaffed and sloppily maintained. When I was given a tour, I hadn’t noticed the death trap of an entrance in the back that my mother, with her walker, would use to come and go. The light at the entrance was burned out. It opened onto perilously uneven ground and had a heavy, pendulous door that neither locked nor stayed open. It never occurred to me that the one ancient, tiny elevator to her second story room could (and did) stop working. The coup de’ gras: one washing machine and dryer for twenty-one residents in varying states of self-soiling feebleness. All this, at one of the nicest places my husband and I looked at.

Truth be told, the place was awful. Like most assisted living places (I like to call them “Ass Livings”) they overpromise and under-deliver. Ocean Breezes was criminally understaffed and sloppily maintained. When I was given a tour, I hadn’t noticed the death trap of an entrance in the back that my mother, with her walker, would use to come and go. The light at the entrance was burned out. It opened onto perilously uneven ground and had a heavy, pendulous door that neither locked nor stayed open. It never occurred to me that the one ancient, tiny elevator to her second story room could (and did) stop working. The coup de’ gras: one washing machine and dryer for twenty-one residents in varying states of self-soiling feebleness. All this, at one of the nicest places my husband and I looked at.

So Mama and I repaired back to the old homestead. I bought us tickets to Atlanta and we—with her walker and two cats—flew south. I also brought Mama a change of clothes in a carry-on bag. Just three months earlier, on our way to California from Georgia she’d had an accident, and I had to borrow a pair of sweatpants from a kind stranger in the airport bathroom. Caring for old people is like wrangling toddlers. You have to be vigilant and attend to nearly every need. Carrying a diaper bag full of stuff for that “just in-case” is a very smart move. Smug with my readiness for anything on our return trip to Georgia, I failed to anticipate one of her cats shitting all over me in the TSA line.

Mama’s house sits on land that has been in the family for over 130 years. In the countryside on the outskirts of Athens, Georgia, Mama had built a house there when she retired—a two story with a big porch. The land is filled with woods growing out of the rich, red Georgia clay, and creeks glittering with mica. My mama and my mama’s mama were born in the oldest house on the property, a short walk from the one Mama built, down Kennedy Road, named for her family. Kennedy Road is populated with dozens of our cousins, their brick or clapboard houses peeking through the pine trees every five acres or so. I love these cousins, solid and sweet. I grew up visiting them most summers. They taught me to drive a truck, make biscuits, roll a cigarette, and say the Lord’s Prayer.

The cousins have a ritual: They walk a couple of times a day up and down Kennedy Road. If it’s nice, they might walk all the way to the mouth of the road where you can look across the highway at the little white church they’ve all gone to for generations. My great grandparents are buried there. My sister is too. Someday my mama will rest there, and when my time comes, I hope there’ll be a spot for me.

I was back at square one, taking care of my mom full-time while trying to find her a safe and (hopefully) pleasant living situation. She could definitely not be left alone, and ‘round-the-clock in-home care was astronomical. I inspected (more carefully this time) a half-dozen places near her house—near enough that the beloved cousins could easily visit and she could still attend the same church.

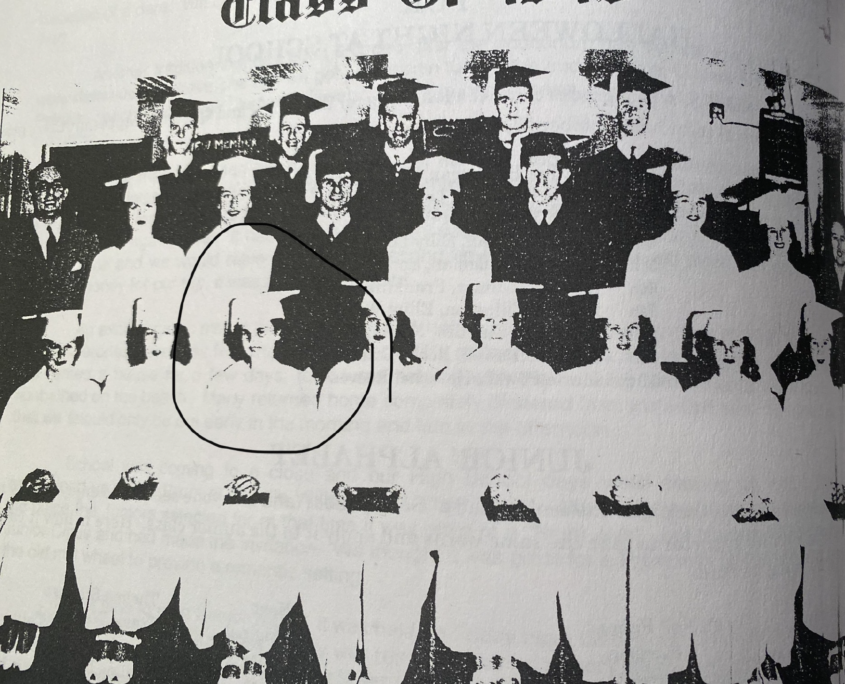

I eliminated the facilities that had raggedy flooring, smelled like piss, or had Fox News on the lobby televisions. I made sure there was a safe resident-to-staff ratio. I kicked the tires and slammed the doors as best I could. In February of 2022, we finally chose a place in Winterville, a few miles from her house. Mama had graduated from Winterville High School in the 1940’s; it’s where she fell in love with her first boyfriend. It seemed pretty great, but none of these places are perfect. The Ass in the Living showed itself right away…the director neglected to inform me when I signed the lease that the place was on lockdown for two weeks due to a case of COVID. That meant no group activities and no visitors for fourteen days. I only discovered this when I was hanging pictures in her new sitting room and watched through the window as one of the cousins drove away. When I called them, they told me that the receptionist said that they couldn’t enter to see Mama until after the quarantine.

I eliminated the facilities that had raggedy flooring, smelled like piss, or had Fox News on the lobby televisions. I made sure there was a safe resident-to-staff ratio. I kicked the tires and slammed the doors as best I could. In February of 2022, we finally chose a place in Winterville, a few miles from her house. Mama had graduated from Winterville High School in the 1940’s; it’s where she fell in love with her first boyfriend. It seemed pretty great, but none of these places are perfect. The Ass in the Living showed itself right away…the director neglected to inform me when I signed the lease that the place was on lockdown for two weeks due to a case of COVID. That meant no group activities and no visitors for fourteen days. I only discovered this when I was hanging pictures in her new sitting room and watched through the window as one of the cousins drove away. When I called them, they told me that the receptionist said that they couldn’t enter to see Mama until after the quarantine.

I was so angry. I went hard core “Karen” on the management. We eventually worked things out. Concessions were made, it all calmed down. Mama seems fairly content there, as in the food is better and she likes being close to Kennedy Road. She still complains about the housekeeping: they don’t know how to make a bed, they don’t vacuum vigorously enough, and someone is stealing her pajamas.

When I went back to visit her at the Ass Living in Georgia in May, the attendants all made a fuss over how sweet my mama was. This alarmed me. If she was being “sweet,” something must be seriously wrong. Perhaps Alzheimer’s was progressing more rapidly than we expected. It’s not that she means to be demanding. Mama has been an obsessive compulsive since long before it was classified in the DSM. She’s regimented. Her whole life she did everything just so. Though she is old, she still feels that everything has to be done just so and right now. However, being almost blind and on a walker, (as she reminds us several times a day), she’s now OCD by proxy, which means she orders you and everyone else around without a stitch of hesitation or gratitude. These are things which simply must be done, and she’d have already done them herself if she wasn’t blind and on a walker!

My mother has been independent and tough her whole life. She mostly ran wild on the farm and around the woods as a kid. When she was nineteen years old, she quit college to join the Air Force during the Korean War. She raised four unruly children on her own. In her forties, a big, sweaty man snatched her purse as she was leaving the Mayfair market. She kicked off her heels and ran after him. When he tripped she was on him in an instant, grabbing fists full of his hair and slamming his head into the ground repeatedly. Bystanders pulled her off of him, and he got away, but she got her purse back. She became a state parole agent in her early fifties. She refused to wear a gun, and she saved more than one parolee’s dog from getting shot by fellow officers. She would get between the dog and the frightened gun wielding officer and get down on the ground. The big dogs would crawl right into her lap and flap their tails. I’ll never forget, late one Thanksgiving when all of her grown kids and several grandchildren were draped around her living room in a overfed stupor, she came out of her room cussing. “I have to go break down that goddamn cocaine dealer’s door and revoke his dumb ass,” she yelled while wriggling in to her Kevlar vest.” She turned back to us before she closed the front door and said in her sweetest drawl. “Don’t worry. I’ll be back in time to make y’all pancakes.”

These days, Mama can become too much in an instant: Suddenly screaming to be understood, or because she dropped something, or braying “UH OH,” when the microwave dings or the phone rings, or saying, “Poopity-doop” when she can’t think of the right words she wants. She will unexpectedly say, “Hoooot!” at some delight, (usually something with a touch of schadenfreude—someone getting insulted or being besmirched). She’ll cry pitiable sobs upon a sudden memory.

I was riding in the car recently with Mama and my grandson, Solly, who is eight. She said to Solly,

“You know Nora. She’s the one who got so fat she couldn’t get out of bed. Hoooot!”

“I don’t know Nora,” Solly replied.

“Well,’” Mama said, changing the subject, “ I never liked my mother…she made me give away my goat when I was five, so I tried to kill her with a rake because she was a bitch.” Then she began to cry as if her heart was broken.

“She died in childbirth! Oh, oh oh, it’s so sad!”

“Who died in childbirth?” Solly asked.

“The GOAT!” Mama yelled.

I put my hand on Solly’s knee to reassure him, and asked her how she knew the goat wouldn’t have died in childbirth anyway, even if she’d kept her.

“Because,” she hissed, “I slept with the goat every night!”

Mama changed the subject again, her crying gone as suddenly as it had started and told us we had to stop to buy more cat food and napkins.

“We live too long,” Mama says. “I want to die.”

One cousin asked her, “If you want to die, why did you get vaccinated?”

“I want to be healthy when I die.”

***

While she was still in California, I got a call from the emergency room, where Mama had been taken by one of her attendants because of a dizzy spell. The ER nurse said my mother was trying to leave and was refusing treatment. I could hear her yelling in the background. “I want to leave now! You fuckers! You goddamned fuckers!”

When I arrived she was trying to dress herself. The nurses looked pained. The ER doc came in and said, “Your enzymes are elevated. You need to stay in the hospital tonight to be observed, and see a cardiologist tomorrow.”

“No. I want to go home,” she said through clenched dentures.

“You could have a heart attack,” warned the doctor.

“I want a heart attack! I want to die!”

Pause.

The doctor told her this was very serious, but my mother leveled her un-seeing glare in the direction of the doctor’s face defiantly. I sighed and shook my head.

After they admitted her and moved her into a room, the nurse came in to ask some questions. She asked if she was depressed, and my mother told her that of course she was depressed. She was old and blind and on a walker. The nurse then asked her if she had thoughts about killing herself.

“Oh hell, I want to die, but I’m not suicidal.”

“Are you safe at home?” the nurse went on. “Is there any abuse?”

Disgusted, my mother answers, “Abuse? I’m not abusive.”

“Mama,” I say, “she’s not asking if you are abusive. She wants to know if you are being abused.”

Stifling a smile, the nurse asks, “Do you want to go Full Code, DNR, or DNI?”

Mama tilts her head to one side.

I ask her, “Do you want to be”—I search for the word—“resurrected” (not exactly the right word but she gets the point) if you have a heart attack?’

“Oh,” she says. Pause. “Yes.”

“Do you want a tube stuck down your throat if you stop breathing?”

Pause. Blink. “Yes.”

“Put her down as full code,” I tell the nurse. As the nurse writes in her chart, Mama says, “I want to die naturally.”

The nurse looks at me.

“I don’t know. Put her down as full code.” I stepped into the hallway and called my sponsor to calm my nerves.

Old people don’t like giving up their autonomy. My headstrong mother is no exception. She drove for years after she couldn’t see three feet in front of her, and it’s only a miracle that she didn’t kill somebody. Even after she stopped driving, she refused to cancel her AAA membership, despite having neither a car nor a driver’s license, because it was a matter of pride.

I don’t blame old folks for wanting to cling to their independence. Getting old ain’t for sissies. And for those people who are able to stay in their homes or with family, that’s wonderful. But I can guarantee there are fewer cases of elder abuse and neglect because of places where the codgers can be taken care of by people who get to go home at the end of their shifts. “Ass Livings” allow families to enjoy the company of their elders without suffering all the maddening and messy grunt work. And it lets the old ones maintain dignity in not relying on constant care from loved ones.

Mama is much happier back in Georgia. They cook food the way she likes it, they sing the church hymns she grew up with, and she’s close to the Cousins. I miss her, but I do have more time for my work and my kids and grandkids. Also, when the pandemic began, I started calling Mama every day that I wasn’t with her. We are closer now than we have been in decades.

So go find yourself a nice old folks’ home, and reserve your spot today—before someone else has to find one for you.

Karen Gaul Schulman is a writer and attorney who lives in Los Angeles, California. She left her family law practice of 30 years to pursue a life of letters and play with her grandchildren. She is currently an MFA candidate at Antioch University LA.