The Passport Nightmare

They say that as much as the human mind can remember experiences of excitement, pleasure, or boredom, it is incapable of similarly remembering pain. Once well again, we can’t put back together the pieces of agony that ruled our days during illness or after an injury. Scientists think this is an evolutionary necessity—if we remembered how bad pain felt, we’d never do anything physically perilous, never give birth to a second child, never get our vaccine boosters.

I know that this is true not only for physical but also for mental pain because I keep traveling abroad even though if I could ever properly remember the pain of international travel I might never leave the U.S. again.

I know that this is true not only for physical but also for mental pain because I keep traveling abroad even though if I could ever properly remember the pain of international travel I might never leave the U.S. again.

A few weeks ago I had cause to remember this, during a long drive home. My partner was behind the wheel when we started talking about how excited we were to go to the Dominican Republic with her sister and parents. Our flight was due to leave in three days.

“Hey, do you mind checking in my purse to make sure my passport’s there?” she said.

I grabbed her purse from the back seat and fished around. “Here it is,” I said. I flipped through its stamps and visas. Then I stopped, feeling a little dizzy. I said, “When we pull over again we should check my passport, too.”

“Why? Are you worried it’s missing?”

“No, I’m pretty sure it’s in my backpack,” I said.

“Then what could be wrong?”

I sighed. “I’m a little worried it might be expired.”

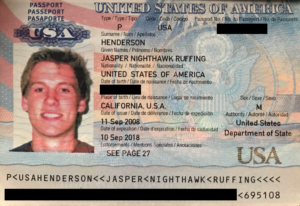

When we stopped on the side of the road in Santa Nella to swap seats, I found my passport and flipped it open. Reader, it was expired. It had expired three months earlier. When I told my partner, she didn’t say anything. I sat back in the car and then got out so I could scream into the Central Valley night. I felt so bad, so stupid.

When we stopped on the side of the road in Santa Nella to swap seats, I found my passport and flipped it open. Reader, it was expired. It had expired three months earlier. When I told my partner, she didn’t say anything. I sat back in the car and then got out so I could scream into the Central Valley night. I felt so bad, so stupid.

You see, this vacation meant a lot to my partner and her family: it was their first real vacation since her mom had been diagnosed with breast cancer and her dad had finished selling her childhood home. It had been a tumultuous few years, but for months we had been looking forward to Christmas with them in the tropics. And it had seemed especially important after a health crisis with my partner’s father had forced them to scuttle their plans to visit us over Thanksgiving. Further, my partner and I were hoping to spend Christmas together for the first time. There was a lot riding on the fact that we were going to have a relaxing week together.

I screamed into the dark night remembering all of this and feeling the anguish of having ruined everything. I felt so ashamed.

Done screaming, we had to keep driving. We were still five hours from home. At first I could only shake my head and laugh ruefully. It seemed a singular screw-up I had committed. But as I settled into my mental anguish, the pain, which at first felt singular, did what pain always does. It reminded me of other, similar pains.

Slowly—one memory at a time—I pieced together that, basically every time I’ve tried to leave the country, through some screw-up or another, my travel plans have almost come to naught.

There was the time I took the subway from my friend’s apartment in Williamsburg out to JFK International Airport in Queens. I hadn’t looked up the travel time and was surprised to find that it took almost two hours to take the subway to the airport. And then when I got there, I realized that I didn’t know what airline my flight was on—all I had written in my notebook were the call numbers: AF158. (I didn’t have a smartphone then.) I guessed that it was Aeroflot, the Russian state airline and so got off at Terminal 2. A kind bookings agent there informed me that AF stood instead for Air France, which left from Terminal 1. “Run,” she said, and I did. I was the last person on the flight.

There was the time I took the subway from my friend’s apartment in Williamsburg out to JFK International Airport in Queens. I hadn’t looked up the travel time and was surprised to find that it took almost two hours to take the subway to the airport. And then when I got there, I realized that I didn’t know what airline my flight was on—all I had written in my notebook were the call numbers: AF158. (I didn’t have a smartphone then.) I guessed that it was Aeroflot, the Russian state airline and so got off at Terminal 2. A kind bookings agent there informed me that AF stood instead for Air France, which left from Terminal 1. “Run,” she said, and I did. I was the last person on the flight.

Probably the worst was the time when I went to India. I thought leaving three weeks to get a visa would be long enough, but I was wrong. The Indian Consulate in San Francisco had recently decided to outsource visa processing to a private company. The only way to get a visa was to mail your passport, two headshots, and a check to the address listed online. I did so and then didn’t hear anything back. As the date of my departure got closer and closer, I spent longer and longer lengths of time on hold with this company’s customer support line. I had a ridiculous clamshell cell phone at the time, and after two hours on hold I would have to plug it in. Usually after about three hours someone would pick up, but they couldn’t promise very much. Finally they told me it would be ready for pick-up at 4:30 p.m. on the day of my flight, which left at 11 p.m. I remember my feeling of wonder when I had the passport in my hands, with the visa pasted in. We went straight to the airport.

Probably the worst was the time when I went to India. I thought leaving three weeks to get a visa would be long enough, but I was wrong. The Indian Consulate in San Francisco had recently decided to outsource visa processing to a private company. The only way to get a visa was to mail your passport, two headshots, and a check to the address listed online. I did so and then didn’t hear anything back. As the date of my departure got closer and closer, I spent longer and longer lengths of time on hold with this company’s customer support line. I had a ridiculous clamshell cell phone at the time, and after two hours on hold I would have to plug it in. Usually after about three hours someone would pick up, but they couldn’t promise very much. Finally they told me it would be ready for pick-up at 4:30 p.m. on the day of my flight, which left at 11 p.m. I remember my feeling of wonder when I had the passport in my hands, with the visa pasted in. We went straight to the airport.

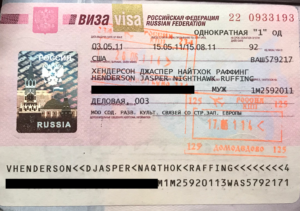

Or maybe the worst time is when I had an eleven-hour layover in Moscow and tried to stay awake the whole time, only to fall asleep in front of my gate an hour before departure. I awoke with a start and was surprised to find that nobody was boarding the flight: it had been moved to a gate on the other side of the airport. I sprinted there but was too late. The airline refused to rebook me. I was distraught, almost crying, until I realized that for about $20 USD I could take a sleeper train to St. Petersburg and skip paying a night’s rent at a hostel.

I could go on, of course. I’ve been blessed to make four extended trips out of the U.S.A. and two shorter ones—by grace of grants to study abroad, a deep devotion to living cheaply, and the blind faith that one of my parents would buy me a plane ticket home when the money ran out. My travel has also been enabled by a fair amount of dumb luck in those situations when a lack of forethought seemed headed for disaster.

But just as often, those in charge have taken an interest in my case and helped me out. The folks in charge of granting Indian Visas eventually agreed to speed up my application in time for my trip. A Public Security Bureau agent in Urumqi, China, once granted me a special 30-day visa so I could continue backpacking around Xinjiang and Tibet. And when I went to the wrong terminal at the last minute at JFK, someone from the airline escorted me to the front of the security line and made sure I made it on my flight.

So much of this must be due simply to me being a white American man. I am always getting a second chance, some help at the finish line, or a special dispensation. This is what people mean when they talk about privilege: the way that the systems that undergird our world can really be looking out for you if you look like me. I have tried this privilege, and I can report that it is an unbelievable relief to land on your feet after doing something idiotic.

So much of this must be due simply to me being a white American man. I am always getting a second chance, some help at the finish line, or a special dispensation. This is what people mean when they talk about privilege: the way that the systems that undergird our world can really be looking out for you if you look like me. I have tried this privilege, and I can report that it is an unbelievable relief to land on your feet after doing something idiotic.

Unfortunately, not everyone is experiencing the world the same way I am. Some people reading this miss their flights even after doing everything right, showing up early, checking every box—because of their name, their nationality, or the color of their skin. Maybe you can’t pick a visa up in person because you live far from a consulate. Some of you can’t afford to take time off and travel at all. And some of you are nervous in your own country that a police officer could stop you for having a tail light out and thereby set into motion your ejection from the U.S.A. into a country you have not been to since you were two years old. I feel blessed not to face these problems—and at the same time furious that others do.

This feels particularly pertinent now, when the current administration is hell-bent on keeping out people who look certain ways, speak certain languages, and worship in certain traditions. Over one thousand children seeking to live in our country have been separated from their parents and kept in cages. The inept government agency that tore them from their parents’ arms didn’t even keep enough records to reunite many of the children with their families after the policy of family separation was putatively cancelled. And as I write this essay, the government is shut down, its workers furloughed or forced to work without pay, because the president demands money to build a physical embodiment of the urge to reject others. The fight to extend privilege to all human beings is a project that has rarely felt so embattled.

But there in the deepening Saturday evening, driving up I-5 and looking out for the off-ramp onto 580, it seemed like even the privileges accorded to 21st-century white American men weren’t going to be enough to get me a passport in time for our Tuesday flight. Sketchy agencies with names like “Fastport Passport” and “Swift Passport Services” promised to overnight your photo to a nearby passport agency—for $569. We called a listed 1-800 number to see if someone on the other end could talk us down from our state of terror, but the number rang a dozen times and a dozen more before we hung up.

We sat in silent in our bucket seats, half-blinded by oncoming headlights, thinking about what Christmas apart would mean. My partner dived into her phone, and I drove. The cruise control carried us at a steady 80.

“Hey, listen to this,” she said. “I’m reading Yelp reviews of the San Francisco Passport Agency. Did you ever hear of a government agency with almost five stars? This is crazy. Here, let me read you one: ‘So impressed with this government agency! They were so organized, and helpful. I didn’t realize I needed a passport for my infant and wasn’t able to get on my 7 a.m. flight. So I headed to the passport agency and had a passport by 3:30 same day, and was able to make an evening flight! Seriously, so amazing.’”

“Hey, listen to this,” she said. “I’m reading Yelp reviews of the San Francisco Passport Agency. Did you ever hear of a government agency with almost five stars? This is crazy. Here, let me read you one: ‘So impressed with this government agency! They were so organized, and helpful. I didn’t realize I needed a passport for my infant and wasn’t able to get on my 7 a.m. flight. So I headed to the passport agency and had a passport by 3:30 same day, and was able to make an evening flight! Seriously, so amazing.’”

We both laughed nervously, and then I begged her to read more. Then I begged her to read even more. There were so many happy stories here. So many tales of people in the same situation I had put us in. Over and over again, people said that they knew it was their own fault, but that the passport agents had been kind, professional, and efficient. We laughed and kept our fingers crossed, feeling that our doom might jam after all, that Christmas might in fact not be canceled. Five hours later we made it home, feeling wrung-out and utterly exhausted.

Monday morning we drove to the city, parked the car in a garage, and by 10:30 a.m. we were through security at the San Francisco Federal Building. The passport office is on the third floor. You can only go there if you have travel plans within the next two weeks. I waited in line for an officer to check that I had the correct documents. I didn’t have an appointment, so I had to wait in a special zone for the line to die down.

This gave me an opportunity to look around the room. There were Americans of every race, age, and religion in that room. Hijabis with strollers sat next to old white guys in Vietnam vet hats. In the “no appointment” section a young Hispanic woman there with her partner and two kids tried to calm down a solo white woman who claimed to have been waiting since seven in the morning. An electronically generated woman’s voice kept announcing variations on, “Ticket C-127 will be seen at Window 17.”

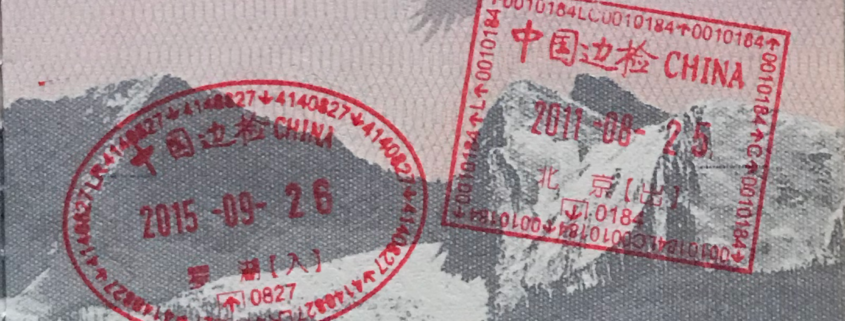

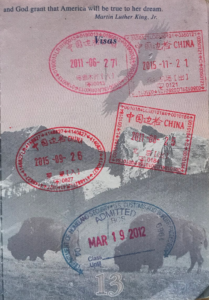

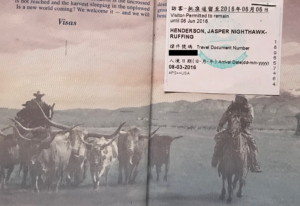

I once spent four days in a row waiting six hours in front of the Chinese embassy in Moscow only to give up on ever getting an appointment, so I was ready for a long wait. But within half an hour I was put in a different queue, and soon my documents were accepted by a nice Chinese-American woman who commented on my Hong Kong immigration slip and convinced me to check the box requesting a passport with extra pages in it. By 1 p.m. we were eating a giant feast of hot pot over in Chinatown, and at 4 p.m. I received my brand new passport. Christmas was saved.

I once spent four days in a row waiting six hours in front of the Chinese embassy in Moscow only to give up on ever getting an appointment, so I was ready for a long wait. But within half an hour I was put in a different queue, and soon my documents were accepted by a nice Chinese-American woman who commented on my Hong Kong immigration slip and convinced me to check the box requesting a passport with extra pages in it. By 1 p.m. we were eating a giant feast of hot pot over in Chinatown, and at 4 p.m. I received my brand new passport. Christmas was saved.

In the elevator down to show my partner the new passport, I met an older Latino father and his handsome son. We quickly showed off our fresh passports to each other, and the old man beamingly told me that his son was about to graduate from college and was going on an international trip. The three of us felt so light, so relieved, that we shook hands when I got off on the second floor. I felt so happy in that moment to think that not only had my passport nightmare been resolved but the passport nightmares of every eligible citizen—regardless of skin color, language, or religion—are daily being resolved by these hardworking federal employees. Thank you, San Francisco Passport Agency.

And that would be the end of the story, but I have to tell you: in celebration of our success, my partner paid for a barber named Vega to give me the hairstyle I had when I was four and ever since have dreamed of having again: a glorious mullet, so short in the front and far past my shoulders in back.

Jasper Henderson is a writer and teacher from the Mendocino Coast. His work has appeared in Joyland, Juked, 7×7, Permasummer, Your Impossible Voice, and an anthology of California writing, Golden State 2017. As a poet-teacher, he works with over four hundred students every year, from third-graders to high school seniors. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University L.A. His cat is named Sybil, after the sibilant, favorite sound of cats across the galaxy.

Jasper Henderson is a writer and teacher from the Mendocino Coast. His work has appeared in Joyland, Juked, 7×7, Permasummer, Your Impossible Voice, and an anthology of California writing, Golden State 2017. As a poet-teacher, he works with over four hundred students every year, from third-graders to high school seniors. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University L.A. His cat is named Sybil, after the sibilant, favorite sound of cats across the galaxy.