The View From 10,000 Feet

One day when I was thirteen, I took my allowance down to Windsong Used Books & Records on Main Street, casually browsed over to the Occult / New Age shelves, and picked out a thin softback with an abstract cover: The Art and Practice of Astral Projection by Ophiel. It promised a simple and effective method for learning how to leave your corporeal form behind and, connected to it only by a thin silver thread, travel through the universe. You could fly over the ocean, spy on your enemies, meet up with distant friends, and even zoom through the stars. I bought the book.

One day when I was thirteen, I took my allowance down to Windsong Used Books & Records on Main Street, casually browsed over to the Occult / New Age shelves, and picked out a thin softback with an abstract cover: The Art and Practice of Astral Projection by Ophiel. It promised a simple and effective method for learning how to leave your corporeal form behind and, connected to it only by a thin silver thread, travel through the universe. You could fly over the ocean, spy on your enemies, meet up with distant friends, and even zoom through the stars. I bought the book.

Back in my room with the door closed, I read that the first task was to send your astral body across the room, just far enough that you could look back and gaze upon your physical body. Night after night I did Ophiel’s muscle relaxing exercises before sleep. I would tense and then release my toes, my calves, my knees, my thighs—working my way up to the crown of my head. Then I tried to astral project.

I’m pretty sure it didn’t work as advertised, though I can’t be sure, because my projecting sessions often ended with me accidentally falling asleep. I don’t remember ever floating up above the clouds or zooming over tens of thousands of miles to visit obscure locales.

I’m pretty sure it didn’t work as advertised, though I can’t be sure, because my projecting sessions often ended with me accidentally falling asleep. I don’t remember ever floating up above the clouds or zooming over tens of thousands of miles to visit obscure locales.

But neither was it entirely ineffective. Many nights after doing the muscle exercises, I would feel my mind lose track of my body. I floated in a void—a roughly Jasper-shaped void, sure—but one that didn’t have any weight. Maybe the sensation was like having a phantom limb, a presence remembered but not felt.

Then, abruptly, my form would distend. My non-corporeal body would get bigger and bigger and bigger, swelling to many times its original size, till my consciousness felt like a pinprick within a gas giant. It was uncomfortable, this cosmic vastness. I tried to reverse the scale, to make my body small again, and through some mysterious muscle I found that I could. But my body shrank and kept shrinking. Before I could stop it, my body was an atom’s width in size. I felt piddly, dwarfed by the immensity of the universe.

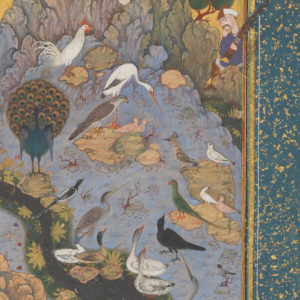

Years after I stopped trying to astral project, I remembered this awful feeling when I came upon this couplet in the 12th-century Persian classic The Canticle of the Birds: “A world’s a mote within this endless sea, / A mote’s a world in its immensity.” Anyone who has looked through both a microscope and a telescope knows that the poet, Farid ud-Din Attar, speaks the truth.

I never really believed that following Ophiel’s technique would let me visit friends across great distances or spy on my crushes. I studied astral projection mainly because I wanted, by whatever means necessary, to fly.

Always, I have wanted to fly. My mom told me that if I could just look at my palms during a dream, then I could control what happened—which is to say I could fly. But that didn’t work for me; instead, in my abandoned dream metropolis the faceless, malevolent figures drew ever closer, till I woke in a cold sweat.

A few months ago, I finally figured out how to fly. When I do it, I can look down at the clouds, at the changing surface of our planet, the valleys and coral-colored deserts, the tropical seas and the shattered arctic ice cap. When I look down at myself, way down in Northern California, sometimes the sea is peaceful while other days heavy surf limns the coastline with whitewater. My favorite are the thousand-mile swirls and eddies of cloud over the South Pacific.

A few months ago, I finally figured out how to fly. When I do it, I can look down at the clouds, at the changing surface of our planet, the valleys and coral-colored deserts, the tropical seas and the shattered arctic ice cap. When I look down at myself, way down in Northern California, sometimes the sea is peaceful while other days heavy surf limns the coastline with whitewater. My favorite are the thousand-mile swirls and eddies of cloud over the South Pacific.

The tool I use is NASA’s EOSDIS Worldview. It loads right into my internet browser, and it gives me images taken just hours before by the Earth Observation System. It includes images taken by a satellite named Terra that swoops over the earth in a sun-synchronous orbit. The satellite passes over me every mid-morning, and by early afternoon I can fly with it. It is quiet up above the atmosphere, looking down. And it’s so beautiful.

Eventually, flying around leads to other questions. Worldview lets you browse images from yesterday, last year, or even fifteen years ago. Just as in the final reckoning physical scale proves to be arbitrary and illusory, so too with time.

Eventually, flying around leads to other questions. Worldview lets you browse images from yesterday, last year, or even fifteen years ago. Just as in the final reckoning physical scale proves to be arbitrary and illusory, so too with time.

It is a strange record. You can hunt for beautiful clouds around Mt. Fuji. Or you can look at New York as photographed from space on the morning of September 11, 2001. In the perfectly cloudless landscape, a long plume of white smoke blows south, over New Jersey. It is a somber, plain image.

In fire season, I turn Worldview’s fire and thermal anomaly data on. It puts a red dot on top of any hot-burning fire big enough to detect from space. If you want to, you can use it to watch the deforestation of the Amazon in real time. I mainly use it to find out about fires that they don’t talk about in the national news.

If you scroll back a year, you can watch the Redwood Complex, Atlas, and Tubbs fires. They burned so dramatically that even from space you can tell how bad they were. What is most shocking is how quickly the fires grew. One day Northern California looked clear and dry. The next, it was choked with smoke and flames.

People often say they want to get very far away. There’s nowhere farther than space. But even up there, you start having thoughts, formulating questions. You get curious about global warming, now that you can see the whole planet spread out below you. You watch ice caps melt. You watch a hurricane swirl into a coast. You watch as snowstorms blanket whole countries. You try to recognize the clouds you saw lit up by last night’s sunset.

And then it’s time to wake up. You close the computer and go outside. Your world is perfectly sized for a human being.

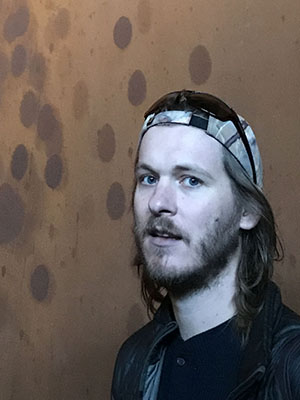

Jasper Henderson is a writer and teacher from the Mendocino Coast. His work has appeared in Joyland, Juked, 7×7, Permasummer, Your Impossible Voice, and an anthology of California writing, Golden State 2017. As a poet-teacher, he works with over four hundred students every year, from third-graders to high school seniors. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University L.A. His cat is named Sybil, after the sibilant, favorite sound of cats across the galaxy.

Jasper Henderson is a writer and teacher from the Mendocino Coast. His work has appeared in Joyland, Juked, 7×7, Permasummer, Your Impossible Voice, and an anthology of California writing, Golden State 2017. As a poet-teacher, he works with over four hundred students every year, from third-graders to high school seniors. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University L.A. His cat is named Sybil, after the sibilant, favorite sound of cats across the galaxy.