Theodore Draws Wolves

[fiction]

Theodore Loupeson’s feet dangled from the straight-backed chair across the desk from Headmaster Clay. Rain battered against the windows of the Briarwright school for boys—runoff poured from the granite lips of gargoyles onto November-bare rose bushes below.

“Theodore.” Headmaster Clay slid a mess of papers onto the desk. “Let’s take a look at your work, shall we?”

Theodore’s work consisted largely of mathematics exercises, half-finished. On the backs of the pages, and in the margins, he had drawn wolves in delicate black ink—remarkably realistic wolves that slithered between the notations and howled at hole-punch moons.

“What do we have here, Theodore?”

“Mathematics, sir.”

“We might have mathematics if you didn’t spend all your time drawing these silly beasts. Have you seen your marks lately? Do you think your education’s some kind of jest?”

Theodore stared at his lap. “No, sir.”

“Do you have any idea why your mother sent you here?”

“So I can study mathematics.”

“And why does she wish for you to study mathematics?”

“So I don’t… so I don’t end up like my father.”

“Your father. A-ne’er-do well in debtor’s prison, I do believe.”

Theodore shook his head. “No!”

Headmaster Clay leaned over the desk. “Excuse me?”

“My father’s dead. The hunter shot him.”

Headmaster Clay exhaled slowly. “Are we really still nursing this infantile fantasy that your father was a wolf?”

Theodore remained silent.

“Your mother will be dreadfully disappointed in you, Theodore. For multiple accounts.”

When Theodore was seven, according to his mother, he had been kidnapped. As he recalled the occasion, he’d been picking white strawberries at the edge of the orchard when a wolf approached him and asked if its gravelly wolf-voice if he would like to come to live in the hills.

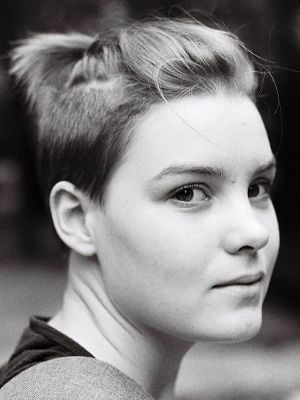

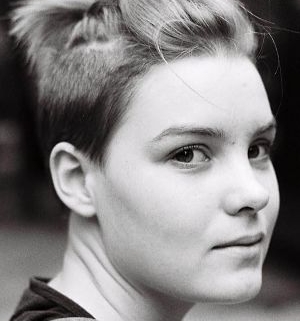

Theo was a quiet boy with middle-parted hair, wet socks, small frame, who talked to himself. His mother, dropping him off at Briarwright, had used the word “unhinged” to describe his recent behavior to the headmaster. Later, she realized he might have overheard. He had overheard. He wore the word as a curse and a badge.

That night he left. He wanted to go home. Into his bookbag, he packed three pairs of socks, three pairs of underwear, a tin of ginger biscuits, all his pocket money, a thermos of tea, and a box of drawing charcoal. At one in the morning when the Nightwatch went on his smoking break, Theo snuck out into the night. The rain had stopped. Everything smelled of petrichor and ozone. Big clouds hurried overhead. Freedom hit him in the lungs as he scurried to the trainyard at the edge of town. For an hour he crouched in the tall thistles, where broken bottles gleamed like onyx in the moonlight, and watched the men move about the tracks, carrying crates of cargo.

Four months ago, when Theodore had first arrived in the station on the train, a steel fence had separated the tracks from the yard. Now the fence had been removed, melted down for the war effort, replaced by flimsy chainlink, already torn in places. When the tracks were clear, Theodore wriggled through one of these holes and slipped aboard a cargo car. At a quarter past three in the morning the train rattled to life. He nuzzled into a bushel of coarse fabric (parachutes he wondered), watched the moon follow the car through a slat in the siding, nibbling the ginger biscuits. Eventually, he fell asleep.

When he woke the train had stopped moving. Thin morning light flooded through the slats. Stiffly, he poked his head out. All clear. He hopped out of the car to see what town he was in.

Not a town at all, it turned out—just a railway junction at the edge of a forest of pines. Theodore shouldered his bag and stared into the trees, which creaked and sang in the wind, ruffling shaggy shadows through their branches. I should be brave now, he thought, because he had read enough stories about children in forests to know that he had to be brave, whatever that meant, though grown-ups rarely rewarded bravery in children. The train blew its whistle and rumbled out of the yard. Watching it leave, Theo was half-relieved he wouldn’t have to sneak aboard again. He turned into the woods. Pine needles brushed soft underfoot. Sap dripped from diseased trunks. The white-bright sun promised warmth that it didn’t quite deliver. As he wandered, he could hear woodpeckers in the canopy but he only caught a glimpse of one specimen: red underwings flitting between boughs.

When Theodore was seven, according to his mother, he had been kidnapped. As he recalled the occasion, he’d been picking white strawberries at the edge of the orchard when a wolf approached him and asked in its gravelly wolf-voice if he would like to come to live in the hills. The day before, Theodore had gotten in an argument with another boy in his class, and the boy challenged him to a duel and said he would bring his grandfather’s sword from the French-and-Indian war to skewer him. If he went with the wolf, he would not have to go to school and get skewered, so he said yes and clambered onto the wolf’s muscular back and twisted his fists into its greasy grey mane. The wolf ran over the ridge, into the hills. It let him down at a den lined with soft grasses. Later that afternoon the wolf brought back a rabbit to eat and set a portion in front of him. It was raw. He wouldn’t eat it, so the wolf left again and came back with a box of matches he’d stolen from outside a farmhouse. Theo lit a fire and roasted the rabbit. The rabbit came out burned and bleeding and tasted wonderful.

All spring he played in and around the den, sometimes alone, sometimes with the wolf, who could not play games with sticks and stones and leaves because he had no thumbs, but knew all kinds of hiding-and-running-and-searching games. Sometimes wolf pups from a nearby litter came by, and Theodore played with them too. He got nipped, and at first, he cried out, but with time the nips only raised the stakes of the game, and he nipped back too. His wolf curled up with him at night to keep him warm. The wolf said, I will always protect you.

They lived like that for eight weeks, until a night when there were voices in the night that weren’t cicadas, but barks and gunshots. Men in heavy canvas pants and sweating armpits hoisted Theodore from the den and pushed him onto the back of a horse with his arms wrapped around the waist of a constable, who took him back to his mother who loved him with ferocity and vanilla and hot baths and at first she frightened him and later he frightened her with his calm grieving and recounting of events. His mother insisted that he had been kidnapped by his-ne’er-do-well father, a debtor and petty thief who wanted domain over the boy—that he had been recovered from his father’s greasy grasp and the father placed in debtor’s prison.

That summer, Theo had begun drawing wolves. He didn’t get angry when his mother challenged him, but he didn’t back down either. So she had decided it was some devilry his father had put into him and sent him off to Briarwright to study mathematics in the hopes of one day becoming a logical and healthy member of society.

Theodore ate the rest of his ginger biscuits and drank the rest of his tea by lunchtime. He wished he had some idea of where he was going. Eventually, the woods thinned he saw a church spire—a town, how fortuitous. It was a small town with just a greengrocer, a butcher, some kind of pub, a well where a girl in red wellingtons stood filling a chipped pitcher with water.

“You came from the woods,” she said. She was exceedingly tall and bony, like a bird. “I watched you come.”

Theo nodded.

“You don’t live here.”

“No.”

“You know what they say.” She sipped from the lip of the pitcher, lowering the water level enough to carry it without spilling. “I shouldn’t be talking to you. I shouldn’t be talking to anyone I don’t know. You could be the man in the dark felt hat. Well. Not really. You’re too small. Still.”

Theodore, dreadfully curious, struggled to maintain a neutral tone. “Who’s that?”

“No one knows, really. I heard he was some kind of German spy, but I don’t think it can be true. If he was a German spy, he’d be lying low, not prowlin’ up and down the countryside terrorizin’.”

“Terrorizin’?”

He did not like the feeling of being alone in the house, so he took the charcoal from his bag and drew wolves on the walls – huge, loping wolves with wind-burnished fur and long snouts, tails streaming behind them – he drew and drew until he was circled by wolves, his protectors, then he lay down on the master bed on the third floor and stared at the ceiling and breathed deliberately until he fell asleep.

“My mother wouldn’t tell me the details but Agatha, my friend from school, says he drags people underground and then stuffs rags in their throats and puts them on a spit and roasts them till they’re crisp.”

Theodore considered this, thought about the rabbit he had eaten. “That’s wicked,” he said. “Do you know where there might be a bakery? I’m awfully hungry.”

She pointed him toward the bakery, where he bought a roll of bread, then plums and cheese at the greengrocer, and sat on the steps of the church to eat. Afterwards, he followed the road out of town. Where it veered north into a farmer’s field, he struck out into the woods. The trees were centuries-old, memory-gnarled, scarred with lightning. It grew dark. Theodore shivered. He should have stayed in town for the night, he thought.

Perhaps the man in the felt hat was behind these very trees, waiting with a string garrote and a butcher’s knife. Unhinged, he remembered his mother whispering. I do believe he’s unhinged. Unhinged people ended up like that, stuffing their victims’ mouths with wadded-up rags and newspapers. Guilt poured over Theodore like a summer rain, chilling him, but leaving him sticky. He hoped his unhinged-ness would be a kind of kinship with the man in the dark felt hat—maybe he wouldn’t hurt him.

He didn’t quite believe that.

He came to a clearing. A house stood in the center of the clearing: peeling cream clapboard, turrets, huge bay windows, a sagging second-story balcony, steep gabled roof plush with moss.

No one had been home for a long time. Theodore tiptoed room to room over wide floorboards hewn from ancient oak.

He did not like the feeling of being alone in the house, so he took the charcoal from his bag and drew wolves on the walls—huge, loping wolves with wind-burnished fur and long snouts, tails streaming behind them. He drew and drew until he was circled by wolves, his protectors, then he lay down on the master bed on the third floor and stared at the ceiling and breathed deliberately until he fell asleep.

Three o’clock in the morning, Theodore dreamed of a creaking downstairs. He woke and lay shivering. The creaking continued, footsteps, then a snarl, then a howl, a crescendo of paws on wood, a thrashing, a man’s voice—

Theodore rolled from the bed, veins hot with fear, ran up the staircase, into the attic, where he crouched between old suitcases and slings of cobwebs. Growls and yells reverberated from downstairs. Then there were noises Theo didn’t have words for. Then Quiet.

Theo stayed upstairs until the sun rose out of the pines and struck the thick glass of the attic windows. He crept back down the stairs, quiet as a ghost, into the drawing room.

The table lay overturned, the sofa ripped, a chair with legs broken off.

A tatter of dark felt. A smear of blood.

The wolves on the walls held the positions he had drawn them in. But they weren’t the same. Their snouts were tacky with blood and their bellies looked full.