Things I Accomplish on My Day Off in Order to Avoid Writing an Essay on Marriage

I lay in my daughter’s bed, where I’ve slept, for a long time awake with my eyes closed, thinking of all the essays I would rather write. I have drafts I want to work on, about birds and sharks and theme parks. I would rather write about foot fungus than write earnestly about marriage. I would rather write about anything but marriage. Which is how I know I’d better write about it.

Instead, I begin complaining about the unseasonable heat. I text my husband about it when he’s at work in a tone which suggests he might be at fault.

I regret the irascible text message. I wonder about conveying “tone” via text in general. I try to find, among the bizarre extant emojis, one that conveys contrition, so I don’t actually have to apologize for being snarky.

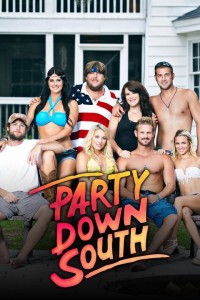

I watch an episode of the reality show Party Down South, now in its fourth season, which gives viewers a look into the lives of nine white southerners who spend summers debauching and tempting early-onset cirrhosis. Or death. (Like, I’m pretty sure the character they call “Daddy,” who takes his beer bong around with him everywhere, is not going to see a season five.) In the episode I watch, the cast member called Boudreaux proposes to his girlfriend. He unwraps an engagement ring from a wad of duct tape, takes a knee and holds it forth. He says of the moment: “I felt like I was kneeling on the brake pedal of the earth.” I think sullenly about how Boudreaux might be better than me at poetry. For some writers, metaphors arrive unbidden, while others must labor. I think about drinking bourbon.

I get depressed from thinking about all the books I won’t have time to read before I’m dead.

I lay on the floor for a little while.

I take my kids to Disneyland for a couple of hours (the Matterhorn looms just 15 minutes north on the I-5). I go on a few rides. I grip my girls, one in each sweaty palm and urge them down Main Street. The false world streams around us. They fatigue quickly and complain about being at Disneyland and I realize that my children, at the ages of six and four, may be reaching early-onset theme park saturation. I drive us home. In the car, they fall asleep and the chub of their cheeks presses into their shoulders. Their tufty hair—their father’s blonde—floats around them in the freeway breeze.

I peruse 501 Italian Verb Conjugations. I think to myself, “It’s important to stay fresh.”

I do Internet research about diseases and affirmatively diagnose myself with a terminal illness. I call my sisters to break the news about my condition, leaving a morose message for one, then having my fear assuaged by the other—a person with both enviable knowledge of human viscera and “common sense.”

I consider my mental map of coffee sellers in a 20-mile radius.

I drive to the coffee seller that pours a chain of hearts into your latte foam. I’m addressed by the amiable, blouse-wearing gentleman at the counter by my first name. I ponder whether there is a coffee shop nearby whose employees don’t know my name. (If I come in early, they always say, “Hi, Mary, one or two today?” If we’re not fighting, I get my husband one, too. I bring it home before he is awake. I place it by his car keys.)

I get high on caffeine and go to a discount retailer. I wander around looking at things no one needs. I contemplate buying a lawn ornament. Specifically, a frog playing a violin. He’s a foot tall and wears a silly smirk. In thinking about the vast blankness of my yard—my husband and I cannot agree on what tree, what bush, how much one ought to water in the new climate—I consider the possibility that I might need two frogs or even a quartet, if I’m going to get serious. I think about how consumption of this kind is likely the opposite of creation, which leads to me shaming myself out of the store.

I acknowledge that if I actually wanted to be a better person I would spend my days off volunteering somewhere, since obviously I’m not going to write a lick.

I listen to the thirty or so voicemail messages that I usually allow to accumulate before I check them. I learn that a month ago my father left a long message about swimming in a race around an ocean pier. I imagine him, a month hence, pulling a rhythmic freestyle in the green, shadow-water near the pilings. I see him swim under the pier and emerge back out into the light of the other side. I think about calling him back. Recently he said that for the holidays this year he’d like to retain an attorney to prepare a will for my husband and me. He said, “You’re not children anymore.”

I think about dyeing my hair. I have never done it, not to cover up the gray. Once, when I was drunk for a while—a period of months after my parents split up—I dyed it bright red, but that’s distant past. I’m 34 and my temples are thoroughly threaded with white. I will be gray-headed by the time I’m 40. (I went to a wedding last weekend with my husband, even though we’re in a fight, and I wore a black dress and swept one side of my hair up with a cluster of silk barrettes made to look like roses. My heart did a heavy clunk when, in the mirror, I saw all the silver streaking back. Right when I was trying, inexplicably, to look pretty for my husband.) All the upkeep of dye seems like a slippery slope. When do you start that? When do you stop? One day you’re going gray and the next day you’re a brunette again. Instead I allow myself to hope that the gray just makes me look prematurely smart.

I acknowledge that I should probably have a will in place.

I contribute GIFs to a longstanding group text I’m involved in. I pat myself on the back for learning how to embed a GIF in a text. I still don’t know what a “GIF” is (acronym? body noise?) and flatter myself that it’s artsy to be willfully daft about pop culture. Then I realize that not speaking whatever language “GIF” belongs to might just be a function of my advanced years.

I think about getting another coffee. I get back on the Internet to review articles about the benefits of coffee in preventing neurodegenerative brain disorders.

I take a dance class at the gym.

I return home and choreograph an original dance routine. For about an hour, I enjoy an outsized notion of my own dancing abilities. I wonder about switching careers to be a professional dancer. (One who leaves to go on tours, so that eventually their home life becomes a foreign place.) I spend a few minutes researching how to become a backup dancer for Beyonce.

I text with friends about how much I dislike football. Ironically, I harangue my husband about his participation in fantasy sports because I think that allegiance to a fantasy roster eclipses love of the game. I fixate on the “right way” to love.

I vacuum my house with extreme care. The high corners of ceilings, the secret crease in the easy chair, the grout of the bathroom tiles. I like the stripes the vacuum leaves on the carpet, but I hate the carpet itself, which my husband thinks is fine—he sees no reason to get rid of a functional thing.

I go to the library and check out books I don’t have time to read.

I eavesdrop on my new next-door neighbors, a young couple with two sons who moved in with their elderly relative. The faceless boys across the fence argue loudly and their little dogs sometimes bark. The bickering happens at our house, too, but our dog barks more than theirs. Ours is a yellow lab mix and he’s getting old and losing his senses. He’s disoriented and scared. When my husband was traveling a lot for work, our dog was younger and his judicious barking made me feel secure (from robbers, ghosts, loneliness). But these days, when my dog hears the clank of the mail dumping through the slot, for example, he runs to the door and barks like a fiend—rearing up and tearing at the wood like a crazed thing, his lips pulled so far back that he shows a terrifying mask of teeth. He’s very difficult to calm. I think about the dog and me going gray together. The dog and me disoriented, snarling.

I let fear of death grip me for a few minutes.

I reflect on how the next-door couple speak so civilly to one another, how kindness is my new foreign language.

I sit at the kitchen table with three laptops in front of me (two for work, one for “writing”) and because I can’t type a word, I shut my eyes. I see an aerial map of my day, traced like one of those apps that shows you where and how far you’ve run. The map is a chaos of flight from here to there, in the house, out of the house, into the city. A scribble of avoidance.

I try and lose it, but the hard essay is everywhere, writing itself. The thing about a bird, a shark, a theme park, is that even when writing about those subjects, the challenge of loving comes at me obliquely. It tracks me, stolid as a hawk, waiting for me to quit running.

Mary Birnbaum is editor of Lunch Ticket’s Diana Woods Memorial Prize in Nonfiction. She holds an MFA from Antioch. She has contributed to Lunch Ticket and The Week. Mary was the 2018 recipient of Disquiet International’s Nonfiction Fellowship and a finalist for Chattahoochee Review’s Lamar York Prize. She resides in Vista, California with her daughters and husband. If you like, you can find her on Twitter @ailishbirnbaum