What I Thought About When It All Went Dark

At the intersection of Hayes and Van Ness, a thin elderly man stands in the median. He wears a baseball cap that covers most of his white, closely cropped hair. He is trim and clean-shaven. Hardly someone whom one would consider homeless. His posture is erect, and proud. He holds a sign with neat and large, legible block letters that reads, “In Need. Sorry to Ask,” and lifts the sign only when the light turns red. He looks away from the vehicles at the light, which makes one wonder how he would be able to see anyone offering help. Drivers would have to wave, or call out to him, or honk to get his attention.

Two blocks down, at the intersection of Duboce and Van Ness, there is another man. He is much younger. His baseball cap is worn and not pulled all the way down, exposing his forehead and matted hair. He has a rough beard and wears a red, Rutgers University sweatshirt. His sign is written on a torn piece of cardboard with uneven edges. The writing is difficult to read. It says, “Homeless. Please Help.” He strolls between cars and aims his menacing stares at the drivers, eliciting guilt and money.

In both cases, drivers roll their windows up and look away to avoid eye contact. It makes one wonder just how much of a difference there is between those driving and those on the street. Only a car door separates their circumstances. How quickly can a man’s fortunes turn from sitting in, to standing outside of a car?

But not everyone looks away. Some will roll the window down, will call the man over, rifle through their purses and wallets and offer to help.

The drivers pull away, and watch in the rear-view mirrors as the homeless men fold their cardboard signs back in half and wait for the next red light, the next hope.

* * *

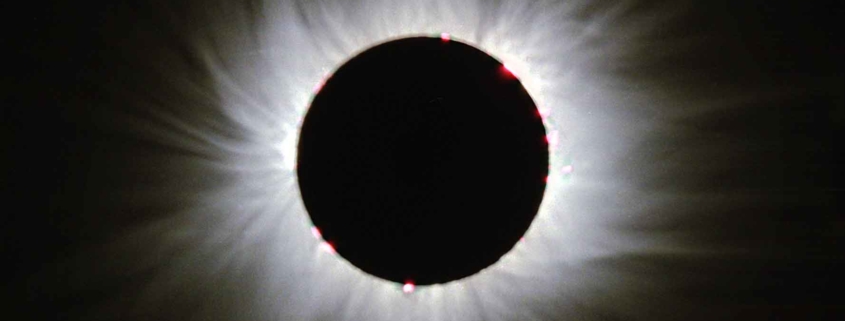

Cubans have a saying, “You can’t cover the entire sky with a single finger.” The light always remains. The recent eclipse brought darkness to the early morning. It was a temporary retreat from judging one another, from the noise, hate, and anxiety about what our future may hold. Everyone paused, looked away from each other and cast their eyes upon the only thing they couldn’t possess, the sky above. In that moment, in the silence, in the awe, there was peace.

It took the moon to block out the sun. But the moon crossing the sun doesn’t cause true darkness. Sometimes, our actions can cast shadows large enough to keep the light from those who need it most.

* * *

In the novel Blindness, Jose Saramago describes a virus that makes people go immediately blind. It spreads quickly and the city where the story takes place descends into panic and chaos. The events of Charlottesville, Barcelona, and the indiscriminate drone bombings in the Middle East are some symptoms of a similar collective virus: the disregard for human life. Whereas losing one’s sight can be devastating, choosing not to see can be just as damaging, particularly when that choice causes the inability to see ourselves in others, when we view their plight as separate from our own.

Mankind has been afflicted with this virus for all recorded history. It appears incurable. It seems even more prevalent and contagious these days, because the instruments by which it spreads are more sophisticated and completely impersonal. Technology drives a wedge between us and our humanity. Our voices are drowned by captions on mobile devices. We’re becoming virtual versions of ourselves. Our images are reduced to pixels on a screen, easily duplicated and stored inside machines.

As if they alone will keep us alive.

* * *

In these times of crisis, when our very survival as a species is at stake, our chosen leader’s willful blindness speaks only for those who have chosen not to see: bomb North Korea (who needs them); get rid of the immigrants (they’re not American); build the wall (keep the rest out); denounce the arts (what’s the point?); privatize education (the disadvantaged need to remain disadvantaged); eliminate health care for the poor (that way we can eliminate the weak and the old); build more jails (for the leftovers); build the pipeline (it’s their land but who cares). Unlike the eclipse, it doesn’t take a moon to block out this conscious lack of humanity. This you CAN stop with a single finger, not to block the light, but to draw the line, point the way. We just have to raise our fingers, together.

* * *

Years before, a young immigrant kid hears the bell ring. It’s his first day of middle school in his new country. He doesn’t speak English and has no friends. He follows the rest of the kids to the yard—because he assumes that’s what he’s supposed to do—where he sits on the long wooden bench against a wall. He is small and brown and, even though he is in seventh grade, his feet don’t reach the ground. In front of him are three baskets. Latinos play basketball on the one nearest to him. Black kids play on the basket to his right. To his left, the Filipinos play on the remaining court. He watches as the ball from the Filipino basket bounces away, rolls past the Latino court, and into where black kids are playing. Everyone stops and the yard goes silent. No one moves. No one dares cross into the other’s court. The young immigrant kid doesn’t understand. Where he comes from, black kids, white kids, and brown kids played together all the time. He begins to wonder where he belongs. He rises and walks through them all to retrieve the ball.

* * *

Long before that, in a small church outside Havana, mass is interrupted when a mare gives birth to a foal right outside the side door. Even the priest comes out to watch the spectacle. A young woman faints from the noonday heat. The foal’s silky legs bow and tremble, uncertain until it finds its balance and rises. The mare rests. Everyone applauds. Some people cry. Some are disgusted.

No need to finish the mass. No need for a sermon. Witnessing birth, the dawn of a new life, everyone is reminded that we will persist.

* * *

In these dark times it is important to remember that power doesn’t speak for us, those who can still see. And while we may feel at a loss watching our government’s blatant disregard for the environment, for human rights, for basic human decency, we must believe that sometimes those who hit the bottom hardest can rebound the highest, because the seeds of rebirth are often found in the darkness of despair. And we, the ones whose sight is not lost, will persist.

Soon, the moon will move, and the light will return.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working towards his MFA in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working towards his MFA in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.