Translation, an Echo of Love: An Interview with Robin Davidson

A poet, translator, and professor, Robin Davidson is the author of Luminous Other, and two chapbooks, Kneeling in the Dojo and City that Ripens on the Tree of the World. Recipient of an NEA fellowship in translation, she is co-translator with Ewa Elżbieta Nowakowska of two volumes of Ewa Lipska’s poems from the Polish, The New Century and, most recently, Dear Ms. Schubert.

A poet, translator, and professor, Robin Davidson is the author of Luminous Other, and two chapbooks, Kneeling in the Dojo and City that Ripens on the Tree of the World. Recipient of an NEA fellowship in translation, she is co-translator with Ewa Elżbieta Nowakowska of two volumes of Ewa Lipska’s poems from the Polish, The New Century and, most recently, Dear Ms. Schubert.

Davidson has received, among other awards, the Ashland Poetry Press Richard Snyder Prize, a Fulbright professorship at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland and a National Endowment for the Arts translation fellowship. She served as the 2015-2017 Poet Laureate for the City of Houston under the leadership of Mayors Annise Parker and Sylvester Turner, and has twice been a finalist for Texas State Poet Laureate in 2017 and 2019. She is a member of the Texas Institute of Letters, and teaches literature and creative writing as professor emeritus of English for the University of Houston-Downtown.

I caught up with Davidson this fall. We chatted about Ewa Lipska’s Dear Ms. Schubert, a book of poems she was a co-translator on, and her newest book of poems Mrs. Schmetterling, which is scheduled for release in December 2021.

Kelly Riggle Hower: I’m excited to be talking with you today, Robin—about Ewa Lipska’s poetry, your poetry, and poetry in general. The first thing I want to ask you is how did poetry snag you? It seems most of us have a story of how it snuck up on us.

Robin Davidson: That’s a good question. I’m almost seventy, and I can remember being thirteen when it happened. My dad was an attorney, and I remember him saying to me, “Never write anything down you don’t want someone else to read.” From the perspective of an attorney, I understand that. And there was the revolutionary in me, and I decided I am going to write down all my secret interior life. So maybe poetry started there. My father was wonderful, and I still miss him, and it’s been years since he died. But that was likely the start of poetry for me.

Also, I grew up in an Episcopal school, so I heard all that beautiful liturgical language and music every day of my life, except for Saturday, so I think it comes from that too.

KRH: I was also raised in the Episcopal church when I was very young and still have the liturgy and hymns, their words and musicality, going through my head: “Oh come, oh come, Emmanuel, to ransom captive Israel…” and “Hail thee festival day!”

RD: We can break into song right here, both of us.

KRH: I notice in your translation of Ewa Lipska, a retention of the strangeness in her poems, and it makes me think of what the writer and translator L. Ali Khan said about them in his New York Journal of Books review of your Dear Ms. Schubert translations. He said, “All poems dwell on the slippery slopes of connotation. Lipska’s even more so,” and that in Lipska’s writing “each poem carries the fragrance though not the structure of a sonnet.” Can you tell me what drew you to Lipska’s poems?

RD: Well, first let me just say that Mr. Khan’s review of the book is incredibly astute. He is a brilliant reviewer. I was so moved by his close reading and his observation of things I hadn’t recognized myself in some of the poems. I’m glad you’re referencing that review because I think it’s really a beautiful one, and he’s done such a service for the publication.

And before I forget, I want to thank Edward Hirsch. Without Professor Hirsch, we wouldn’t have found the great editors at Princeton University Press’s Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation. Great editors matter, and Peter Cole, Rosanna Warren, and Richard Sieburth read every word again and again, all 66 poems in the book.

Regarding Khan’s observations about Ewa’s work, yes, she’s quintessentially modern in her use of sardonic wit and irony, a 21st-century poet, for sure. She was a visual artist and very interested in Dali—and even the clock, the hand that falls out of the eye. She’s very surrealistic in her imagination. But not without coming from a deep knowledge of tradition. It seems to me what’s most interesting about any great artist is that they have literary ancestors, musical and visual arts ancestors to riff off of or diverge from. So, yes, as Mr. Khan says, there is the essence of the sonnet. To be anti-lyric, as Lipska is, you have to know what the lyric is.

The thing that brings that kind of closeness to the sonnet is love.

The thing that brings that kind of closeness to the sonnet is love. In her work she addresses authoritarian, totalitarian regimes and extremist government’s use of jargon, the jargon of technology, music, banking, of the Books of Revelation and Genesis. It’s brilliantly transformed by her use of unusual metaphors, and she uses all these ideas as vehicles for the interrogation of many ideas that she’s concerned with. Ideas that most Europeans would be concerned with and that Americans should be, if they aren’t already. And she addresses these within the framework of these unusual love poems, because even as you address social change, the individual is what you can most impact. What maybe you and Khan both sense is that echo of love in all her poems.

KRH::I love what you just told us there, what Ewa Lipska shows us in her poems—that to be anti-lyrical is not to be anti-love. I’d like to read you my favorite poem of hers, a poem I feel evokes this balance she manages, her poem “Piano.” Would that be okay?

RD: Oh, please do.

KRH:

Piano

Dear Ms. Schubert, the piano tuner tried to calm our shaky

Steinway. Its heart pounded in a resonant box like a hammer.

He had to change the pitch of the key and shorten the

distance of the hammer strokes from the strings. So let’s play

it again, dear Ms. Schubert, because it’s still too early to be too late.

RD: It’s a wonderful juxtaposition of the lyric and the ironic, and the love that interweaves those things. It’s great. Thank you for reading. I’m so glad you love her poems. I have a poem I want to read later that may be kind of an answer to that poem.

KRH: Yes, please. I want to ask you what it’s like doing translation, particularly with another translator? I know you’re working to translate the “truth” of what is written, audacious as that sounds, rather than the literal words written—though sometimes, with Lipska, you want to stay with Lipska’s weird image choices. You worked with Ewa Elżbieta Nowakowska, a poet and native Polish speaker, to do that. Can you tell me how you two worked together as translators?

RB: Well, I love her, the other Ewa. I call her Ewa N., or sometimes little Ewa, to distinguish between her and Ewa Lipska. And I was introduced to her by Lipska.

Let me say first that my beloved teacher, the poet Adam Zagajewski, who died March 21, introduced me to Lipska’s poems in a Modern Thought class I took with him. He introduced us to many Polish poets, both men and women, beginning with Alexander Wat and moving forward to the 21st century.

Adam admired Lipska and included her work in the course. I fell in love with Lipska’s poems, reading the wonderful Barbara Plebanek’s and Tony Howard’s translation of Poet? Criminal? Madman?. I loved the poems but could tell there was a lot I didn’t understand because I couldn’t read the original. Adam wrote to Lipska to have her send me a copy of her most recent book at the time. And it was all in Polish, which makes sense, and, of course, I couldn’t read it. So I told Adam I wanted to go to Poland and learn Polish, and he helped me get there. I got a Fulbright professorship with the Jagiellonian University, to teach in Kraków, and that’s how I met Lipska.

Then in January 2003 I met Nowakowska. Ewa Lipska invited Nowakowska and me for coffee at her apartment. Nowakowska and I decided we would meet halfway between her apartment and my apartment to walk the rest of the way to Lipska’s house together. We liked that agreement, because it is really what we do as collaborators in the translation process.

We drank Viennese coffee at Lipska’s because she had spent many years in Austria, as the First Secretary of the Polish Embassy in Vienna. And she introduced me to Ewa N. because she knew I was just a baby Polish speaker at that time…wasn’t even a Polish speaker, but a baby Polish reader.

I was studying at that time with the American consulate’s Polish teacher, Bogumiła Osiak. I still remember her as the kindest and most beautiful woman I’d ever met, and I loved her. She was like a Polish mother to me. I was so new in the process, and she was so helpful, as was Nowakowska. She and I would meet for coffee and take long walks talking and talking that year I was in Kraków.

We spent lots of time together face to face at the beginning of the translation process, beginning to know each other as poets—Nowakowska is a poet as well as a translator. We worked together to publish a book of translations through Northwestern University Press in 2009, The New Century, just in English, not bilingual. It’s the book Nowakowska and I collaborated on first. Because my Polish was slim, I would type up all the Polish, and Nowakowska would give a preliminary translation of it, then I would begin to bring it into a stronger English, and more of an echo of the original. Walter Benjamin, a remarkable philosopher who was kind of a closet poet, says that the heart of literary translation is to attend to the heart of the original, an echo, the spirit of the original. That’s what we tried to do.

KRH: The poet Piotr Florczyk, in our Antioch MFA translation class, gave us an essay by Jacek Gutorow, “Letter from Poland: On translating Poetry,” in which Gutorow referenced Kenneth Rexroth’s vision of translation. Rexroth suggested less of a literal word for word translation and more an evocation. It sounds like Rexroth’s evocation is much like Walter Benjamin’s echo. It gave me the courage to try to translate.

RD: I don’t think I’d have finished the translation for the Dear Ms. Schubert book if Piotr hadn’t said “You can do it. Just do it.” And it certainly helped that Lipska is a living poet, and she could answer questions for us. That was really great. She doesn’t want her metaphors tampered with or smoothed out in translation, because she chose them for a specific reason and effect; so we had to figure out a way to bring the poems forward meaningfully in English while retaining their metaphorical lives.

She doesn’t want her metaphors tampered with or smoothed out in translation, because she chose them for a specific reason and effect; so we had to figure out a way to bring the poems forward meaningfully in English while retaining their metaphorical lives.

KRH: I want to talk a little bit about your Mrs. Schmetterling poems in City That Ripens On The Tree Of The World. Those poems are magical to me.

RD: I have to tell you where this title comes from, so I’m not a plagiarist. The title is a line from the Polish novelist Magdalena Tulli’s book called Dreams and Stones. Several of her books are translated by Bill Johnston, and she is well worth reading. I love that book, and it’s a book about a mythic city. Her city is Warsaw, and that was the inspiration for my title.

KRH: I love that Mrs. Schmetterling has a kind of conversation with Ms. Schubert, though they are very different women. In the book’s first poem she starts out with such self-effacement, and by the last poem has become this large almost-mythic persona. In that first poem, “Mrs. Schmetterling Kneels in a Garden,” we are told “Mrs. Schmetterling, let’s call her Judith, married. / She is neither great musician nor poet. / Not scientist or historian. She is ordinary. / Any century’s woman…” And yet you’ve named her Judith, like the biblical Judith, a woman who is not only from any century but in some ways from all centuries, taking off a man’s head to save her people. There’s a coiled power in Mrs. Schmetterling that wants out. By book’s end, in “What Mrs. Schmetterling Wants,” she’s standing at the gate of the city and claiming the whole landscape. Could you speak to that?

RD: You have just identified, really, the whole imagination underlying those poems. I told Lipska, “These poems are my responses to your poems.” They are a conversation between two women poet personaes, in a mysterious way. That is how Mrs. Schmetterling started.

KRH: By the end of the book she’s not nearly so conventional as she started, just as Ms. Schubert is less conventional as Lipska’s poems go along than at the start. That said, Mrs. Schmetterling seems to feel more constraints than Ms. Schubert does, and I would say that those are cultural constraints?

RD:Yes, they are. When translating Lipska’s Ms. Schubert poems, we decided to go with Ms. rather than Mrs. as the name for Ms. Schubert. Pani Schubert could be translated as “Ms.” or “Mrs.,” and we decided that Ms. Schubert reflected her better. Ms. Schubert is an independent woman. She is independent of the patriarchy, she’s independent of a representative male in the community. But I realized that was not the right word for Mrs. Schmetterling because her conflict is different. She is not a European woman, not an independent woman. She’s really someone who has developed over the course of a lifetime and is struggling with the complexity of her life and the constraints of her life. She is still part of a culture that is at present quite patriarchal. Like Ms. Schubert, she has moved away from those constraints, but this is not Europe. The U.S. is a very particular kind of nation, and that has been part of Mrs. Schmetterling’s journey.

KRH: Can you tell me more about Ms. Schmetterling’s journey?

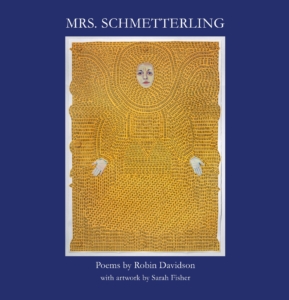

RD: Well, Mrs. Schmetterling has come a long way, and there are now twenty-two new Mrs. Schmetterling poems in my upcoming book Mrs. Schmetterling. Askold Melnyczuk, the editor of Arrowsmith Press, is a wonderful Ukrainian-American writer whose parents and whole family were refugees to the U.S. from Ukraine. Anyway, he accepted these poems through a serendipitous process. He took them very recently, and they are going to come out the first week of December.

And a gentleman, Ezra Fox, who is a graphic designer and senior editor with Arrowsmith, he is a genius and just lovely, and this has been the fastest experience I’ve had in publishing anything. I just got a look at the cover, and this image is a work of visual art by a woman, Sarah Fisher, a friend of mine here in Houston who is a deeply talented artist.

All those yellow elements on there are laundry stickers, and they say “stain.” When I saw that on the wall at Houston’s Lawndale Art Center, where I was attending a reading, I thought “Wow, is this a nun? Is this an angel? What is this woman? And when I got close I realized, “Oh, my God, these are little yellow stickers that say ‘Stain’!”

When I saw that, I thought, this is it, this is Mrs. Schmetterling. I got in touch with Sarah, and we’ve been friends ever since. I wrote a poem in response to the mixed media work of art, so there’s this chapbook now. It’s just twenty-two poems interwoven with several of Sarah’s images in the “Stain Cycle.” I love when poetry and visual art respond to one another, and I have found her mixed media pieces so inspiring.

KRH: I have developed a real soft spot for Mrs. Schmetterling, and I’m so excited to see what she is up to in this next collection.

You promised to read a poem by Lipska that sort of answers that poem “Piano,” which I read, and I would so love to hear one of your Mrs. Schmetterling poems as well.

RD: My favorite poem of Ewa’s in Dear Ms. Schubert is probably this one:

The Large Hadron Collider

Dear Ms. Schubert, because I believe in an afterlife,

we’re bound to meet in the large Hadron Collider.

You’ll probably be a fraction of the number I’ll add

to myself. The sum won’t require any explanation.

It’s more or less what love equals. Minus disaster.

KRH: After I read that one aloud in my book group, we sat in stunned silence. It astonishes.

RD: Yes, it does.

KRH: Will you read us one more Mrs. Schmetterling poem before we have to say goodbye for now?

RD: I’ll read the poem, “Stain,” that I wrote in response to Sara Fisher’s multi-media piece. And let me just say, before I read this, thank you so much for the chance to talk about Ewa’s work and my own work. You know, it’s such fun to have this opportunity.

KRH: My thanks to you, Robin. This was a joy for me.

RD: Okay, here was my starting point for Mrs. Schmetterling:

Stain

Mrs. Schmetterling hears the Dean of Coventry Cathedral say,

We are all angels. We can all be ambassadors of forgiveness.

The figure on the canvas looks like an angel, or a nun,

until Mrs. Schmetterling sees she’s made of tiny, yellow rectangles.

Strips of tape that read, Stain.

The figure on the canvas is made of laundry stickers and failures,

one after another, an avalanche of human error.

The Dean says Coventry Cathedral rose from the ruins, rebuilt

with charred beams and marked with the Cross of Nails

to forgive the wounds of history, cleanse the traces.

The figure on the canvas has the face and hands of a woman.

Eve in a habit. Eve with yellow, laundry tape wings.

Mrs. Schmetterling too is an accumulation of stains.

She wonders how she, or anyone, removes the stains of history.

She studies the woman’s face, her open palms

for a salvation story, the human sacrifice required of her.

But what she sees is a labyrinthine body of sleeves and wings,

tunic and coif, a weave of wounds and stains

whose beauty shines like a mother-father-god.

Mrs. Schmetterling hears the rhyme of stain in angels.

She thinks of history as a planetary dry cleaners

where humankind’s soiled laundry is sorted and marked,

soaked with solvent or water, and waits for ablution

or ash.

Kelly Riggle Hower is a poet in Antioch L.A.’s MFA program, a returned Peace Corps Volunteer, and a public school teacher. She is currently teaching 400 K-2 art students at L.A.’s Westwood Charter Public School. Kelly has won the Richard Hugo House Poetry of Place Competition, and her poetry publications include The Seattle Times, Worldview Magazine, The Raven Chronicles, and the Seattle Metro’s Poetry and Arts on Buses Project. One of Kelly’s favorite poetry memories is the year she and her daughter Roslyn were both Poetry and Arts on Buses Project winners, with their poems riding together in the big rolling gallery of the public transportation system.