Trust Your Gut: An Interview with Tom Schulman

Tom Schulman won an Academy Award for his screenplay Dead Poets Society, a film also nominated for Best Picture, Best Director (Peter Weir), and Best Actor (Robin Williams). His new movie, Double Down South, is the second film Schulman directed as well as wrote.

Tom Schulman won an Academy Award for his screenplay Dead Poets Society, a film also nominated for Best Picture, Best Director (Peter Weir), and Best Actor (Robin Williams). His new movie, Double Down South, is the second film Schulman directed as well as wrote.

His first writer/director credit was 8 Heads in a Duffle Bag, starring Joe Pesci. He also wrote or co-wrote Honey, I Shrunk the Kids; Second Sight; What About Bob?; Welcome to Mooseport; Holy Man; Medicine Man; The Gladiator; and A Father’s Revenge. He was an executive producer on Indecent Proposal and Me, Myself and Irene. He co-wrote and co-produced The Anatomy of Hope, a pilot made for HBO.

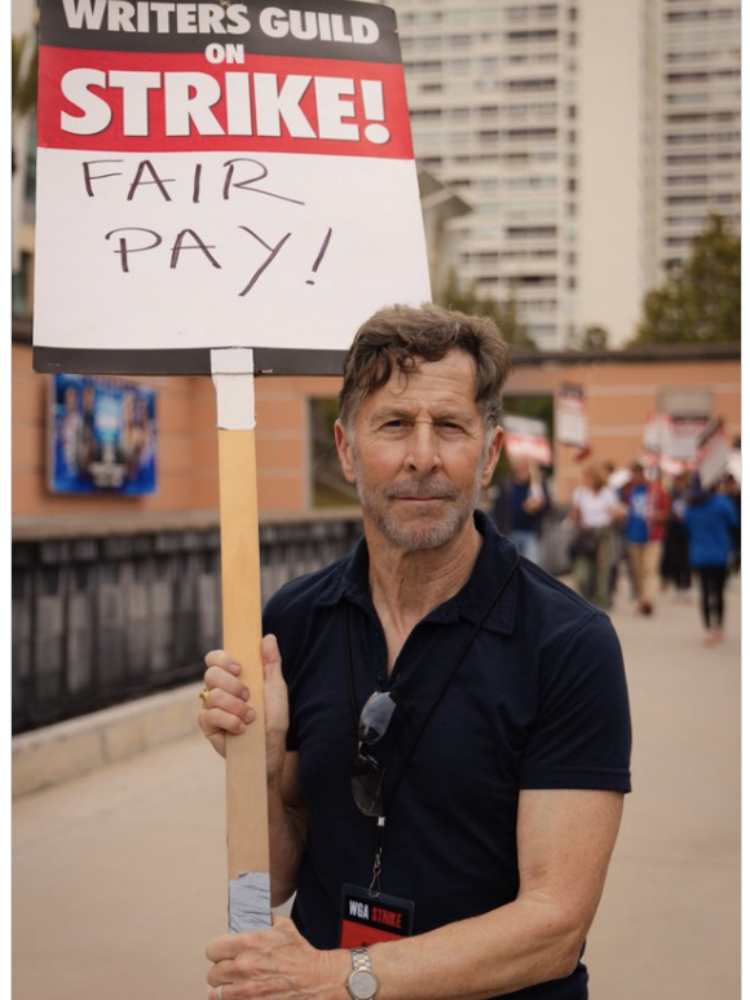

For the Writers Guild of America West, Schulman has served on the board, as vice president, and on their negotiating team during their 2023 strike. He was president of the Writers Guild Foundation and serves on its board.

A graduate of Vanderbilt University with a BA in philosophy, Schulman studied at the USC Graduate School of Cinema, with Jack Garfein at the Actors and Director’s Lab, and later with Joan Darling.

Schulman and I met for this interview via Zoom on February 20, 2024.

Kevin J. Cummins: How did you come to write your new movie, Double Down South?

Tom Schulman: I started writing Double Down South based on a memory of a woman who came into a pool hall I hung out in, in Nashville, when I was 13 or 14. The people who ran the place were all called Nick—nasty guys who said things 14-year-olds shouldn’t hear and didn’t understand but knew were inappropriate. And this place had Keno, a diabolical pool game with betting that doubles over and over out of your control, so you could risk a small amount of money and end up losing your shirt. This attractive woman entered a man’s world to play Keno, and though she made an impression then, I forgot about her until the first year of COVID.

Another side of me was thinking about the Old South versus the New South.

KJC: How did you choose to set the film in 1998? Was that when the Old South became the New South?

TS: To my mind, yes. Nashville, my hometown, was becoming more cosmopolitan. The Houston Oilers had moved there so the city suddenly had black athletes eating in places where only white people used to eat. After Obama was first elected, the New York Times published a map of the United States showing which counties voted more Democrat and which voted more Republican. You could draw an ellipse like an eye from Knoxville to Oklahoma; it was virtually the only part of the country that went more Republican and that included Nashville. My hometown’s reaction to a black candidate for President roughly, and coincidentally, coincided with the demise of Keno.

KJC: Double Down South is the second film you’ve both written and directed. 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag was the first. What’s a lesson you learned with 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag that helped you to shepherd Double Down South to the screen?

TS: On every project, I’ve learned this the hard way: If your gut is telling you something over and over, in spite of pressure from others, you’ve got to be uncompromising. You may be wrong, but there is nothing worse than making other people’s mistakes.

With 8 Heads, the producers and studio were adamant about casting a particular role their way. When you’re dealing with a studio, they’re the boss, and they hold all the cards. “If you don’t do it our way, we’ll either take the movie away from you, or we won’t make it at all.”

To work on movies is exciting, but not always fun. It’s a constant struggle. It’s hard to get studios to make a movie. It’s even harder with an indie when you have no guarantee of distribution.

So I caved. But I told them, “When we’re watching this movie in a screening room a year from now, this casting decision will stick out as a mistake we’re all going to regret.” And I was right.

KJC: As a screenwriter who trusts his gut, do you prefer to make small, independent films? Or do you think, “It’s fun to make movies, period. So, I’m happy to work on a big studio movie.”

TS: To work on movies is exciting, but not always fun. It’s a constant struggle. It’s hard to get studios to make a movie. It’s even harder with an indie when you have no guarantee of distribution. With studios, most of the time they work hard to get your movie seen. With an indie, that’s a crapshoot.

KJC: In the credits for Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, you’re listed as a co-writer. In A Father’s Revenge, you’re credited with “Story by…” but not “Written by….” For Dead Poets Society, you’re the one writer. Could you talk about the differences among those experiences?

TS: There’s a code in the way the Writers Guild determines writers’ credits. If there’s an ampersand between two writers, they wrote it together. If the word and is between them, then they wrote separately. The writer in the first position is either the first writer or the more important writer. For instance, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids was a pre-existing script the studio hired me to rewrite. The other writer got story credit because it was his idea. He and I both got credit for writing the screenplay. With A Father’s Revenge, I was rewritten, and the Guild determined I deserved story credit but not screenplay credit. Dead Poets Society was all mine, so I got sole credit.

KJC: How do you feel about outlining versus discovering a story by writing without knowing where you’re going? Which of those styles is more in keeping with your practice?

TS: I don’t think you can write a screenplay until you know your ending. The ending is the target, and you have to know where to aim your arrow. You may start with a rough idea of your ending, but you have to do a lot of writing to discover exactly what your ending is, and once you do then you usually have to re-aim and revise, often extensively.

I take notes about my story for days, weeks, months, sometimes years. Once I feel like I have most of the story in hand, I’ll organize my notes into clean paragraphs, print them, slice every paragraph away from the others, make a pile of all those strips of paper, clear the floor, and start laying out all those notes in story order. This process can take weeks, but it has the great benefit of allowing my unconscious to work because while I’m working on say scene 30, the answer to a problem I have with scene 2 will come to me. And so on. At the end of the process, I’ll have every scene laid out in great detail in order on the floor. I’ll tape all the strips onto 8 by 10 sheets of paper, three-hole punch them, put them in a notebook, open the notebook and start the first draft.

KJC: Viewing the family dynamics in your movies made me wonder about your upbringing and your journey to become a writer. There’s a theme of resistance to authority in Dead Poets Society; What About Bob?; Honey, I Shrunk the Kids; A Father’s Revenge; The Gladiator; and Double Down South. These six films all portray tension inside a family. What authority figure in your childhood offered you expectations? And were you given room to negotiate?

I take notes about my story for days, weeks, months, sometimes years. Once I feel like I have most of the story in hand, I’ll organize my notes into clean paragraphs, print them, slice every paragraph away from the others, make a pile of all those strips of paper, clear the floor, and start laying out all those notes in story order.

TS: My father probably had the strongest influence on me. He grew up with an authoritarian father. By the time I knew my grandfather, he loved anything any of his grandchildren did. But when he raised my father he was incredibly strict. He gave my father no choice but to become a doctor. My father was loving and sensitive, but like his father he was very critical and controlling of me until I was 12.

At 12, I went away to a summer camp, and the camp director, unbeknownst to us kids, sat outside our cabins after lights out, listened to our conversations, and made notes. In the winter, he came to Nashville to show the camp film, recruit new campers, and visit with the campers’ parents. Whether the parents liked it or not, they had to listen to his analysis of their child. He told my father he was destroying my self-esteem, that he was too harsh on me, and he needed to let go. According to my mother, my father was devastated that he had hurt me, and for a few days he was almost suicidal. My father never said anything to me about it, but he suddenly became more open, less strict, and more available. For example, when I told him I wanted to be a doctor, he said, “Think about that. Don’t do it for me. Do it for yourself.” So I decided I didn’t want to be a doctor.

In those days, my academic writing was woeful. When I started public high school in ninth grade, Nashville had merged two high schools into one, and it was ridiculously overcrowded. There were 60 kids in every class, two, sometimes three students per desk, so 90 percent of the teachers’ time was spent trying to maintain order. There was very little learning going on. My parents didn’t want to send me to a private school, and I didn’t want to go to one, but the public school education was so bad that I applied to a private all-boys school called Montgomery Bell Academy. I got in, but the head of the English department said, “You need to work on your writing this summer. We’re giving you four novels, and we want you to read them each twice.” So I read Les Misérables, Crime and Punishment, The Secret Sharer, and Heart of Darkness twice. In September, they had me write a sample essay and declared my writing skills sufficiently improved. Their idea, obviously, was that reading great writers trains your brain and teaches you how to write, and I guess it worked.

KJC: What makes a satisfying relationship for you as a writer working with a director?

TS: With Peter Weir on Dead Poets Society, he was very open, and it felt like we had a collegial dialogue and had no problems challenging each other if we disagreed.

In the first draft of the script, three-quarters of the way through the story, the boys arrive in the classroom, and Mr. Keating is absent. The substitute teacher tells them Keating is in the hospital. The boys visit him and learn he has Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. That disease won’t kill him right away, but will shorten his life, and the boys realize that’s where his passion for carpe diem comes from.

Peter told me that the illness was a mistake and said, “This will be the easiest rewrite you’ve ever done. Just take out pages 70 to 74 and nothing else has to change because Keating’s illness is never mentioned again in the script.”

I said, “Then how will we know why he’s so attached to carpe diem?”

“He just is,” Peter said. “Does he have to be dying young to be attached to that?”

Now, many people who read the script had told me that they cried when they read that scene so I was reluctant to take it out. So Peter said to me, “I’m not going to insist you take it out, but I will not direct the movie unless you want to take it out.” We argued about the scene for days. I was sure I’d convince him to keep it in, and he was sure it should come out because he thought it would swallow everything else in the story. Then one day he said, “Look, anybody might stand up for a teacher simply because he’s dying, but if he’s not dying and they stand up, they can only be standing up for what he taught them. Since that’s what you’re trying to convey, don’t confuse the issue.” I immediately realized he was right, and I took the scene out.

That to me is how a writer and director should work together.

KJC: What advice would you give a young screenwriter?

TS: Write a lot. Writing is a muscle. The more you write, the stronger that muscle becomes. Be patient and give yourself some time to develop. It takes people three years to become a lawyer, four to eight years, or more, to become a doctor, so realize that becoming a good writer takes time. Ideally, write stories that only you can tell. The more you know about the characters and story you’re telling, the more personal it will be and the more it will resonate with the audience.

As a practical matter, when you’re starting out, write stories you can make for $30,000 instead of 30 million and find stories where the limitations of the budget are an asset. Darren Aronofsky made Pi, his first feature, with a hand-wind Bolex 16 mm camera with only 20 seconds of run-time with each wind. But since Pi was about a man who’s possibly losing his mind, the fast cutting, shaky camera style fit the subject matter, and the film was better because of it.

KJC: Is there a genre you find easier to write, or one you find more challenging?

TS: Every time I start a script, I fear I’m not up to it. Comedy feels like the hardest thing to write, but for me it’s also the most satisfying. To start, I try not to censor myself. I’ll write bad scenes and bad jokes. But if I feel like there is at least something funny there then I’ll relax a little. In the next pass, if more funny stuff comes up and more bad stuff goes away, then I’ll get more confidence, and slowly the script will get better and better.

KJC: I watched two of your early movies—A Father’s Revenge and The Gladiator—both gritty thrillers. Does their warrior toughness reflect a mindset you had as a young screenwriter?

TS: I have no idea. The first two scripts I wrote were…. I was working for a guy who made educational films. I was a schlepper, helping him do any and everything on his movies. I was an assistant director, an assistant editor, an assistant lighting person. He was a great boss, and he taught me a lot.

One Monday, he came to the office and said, “I met some people over the weekend who want to back me in making a low-budget film so I need a script. I’ll pay one of you $5,000”—which was a fortune back then—“if you can write a script by the end of the week.”

I volunteered and he asked, “Have you ever written a feature?” And I said, “No, but I’ve written some shorts, and I think I can do it.” So, I wrote a low budget horror film in five days. My boss liked it and gave it to the backers, but they said, “We’re sorry but we’re Mormons, and we can’t do a horror film. Can you make a family film?” So my boss got another writer to write the family film.

When we made the family film, I was an assistant director on the set, and the Mormon backers were extras. One day they said to me, “We really liked your horror film. We’d like to hire you to write a comedy.” I pitched them an idea, they paid me to write it, and they even let me shoot a day of it to see if I could direct it. The night after I showed them the scene I’d directed, the lead Mormon backer died of a heart attack, so that was that.

But I had two scripts, and they got me an agent, and my agent said, “I don’t know if we can sell these scripts, but I can get people interested in you. Write something else.”

I wrote Dead Poets Society in 1985. My agent at the time told me, “This is the best script I’ve ever read. But it’s all boys, there’s no sex, it’s about poetry, and name me one commercially successful movie set in a boarding school.

A few weeks later, I woke up with this idea of a middle class doctor whose daughter gets kidnapped by terrorists on her honeymoon in Italy. So the doctor kidnaps the head terrorist’s father in hopes of making an exchange. The terrorist sends the doctor his daughter’s severed finger with her wedding ring on it, so the doctor sends the terrorist his father’s finger, but it’s actually the doctor’s finger, with the father’s wedding band on it.

That script was called Rampage and eventually got made into a TV movie of the week called A Father’s Revenge.

With The Gladiator, a producer friend called me and said, “Let’s do an urban Road Warrior, set in LA.” So I came up with this guy in a state of despair after his wife is killed by a drunk driver. He builds this truck with a rig that can lasso drunk drivers’ cars and pull them off the road. I wrote a detailed treatment of that story, and it ended up as The Gladiator, a movie of the week on ABC.

I wrote Dead Poets Society in 1985. My agent at the time told me, “This is the best script I’ve ever read. But it’s all boys, there’s no sex, it’s about poetry, and name me one commercially successful movie set in a boarding school. I can’t sell it, but I can use it as a calling card to maybe get you work.” I told him I wanted to try to get it made so he told me I’d have to get another agent.

I sent it to five agents and four passed. The one who was interested was at a big agency and he said, “I read about half of this, and I think I can find actors at the agency who will want to do it. I’ll take a shot.” Every week, I feared he would read the second half and fire me.

Two years later, a producer who was friends with Jeff Katzenberg read it, and a director who had a deal at Disney read it and wanted to do it. Disney had already passed on it, but Katzenberg read it on a Monday morning and bought it later that night.

Two days later, I got 40 pages of notes. The notes began, “We love this script, but it’s not properly plotted. Let’s start with the teacher when he’s in high school, follow him through college, etc.” And I’m like, “Oh, my God, they’re ruining it!”

I called my agent, and he said, “You’ve got a meeting on Friday with Katzenberg, so go in there and make your case.”

I didn’t sleep for two days. When I got to Katzenberg’s office, I was seated with some of the studio’s junior executives. Meanwhile Katzenberg was across the room, sitting at his desk, reading something.

The junior execs and I made small talk, but I was dying inside, trying to figure out how I was going to defend my script, when Katzenberg turns and asks, “Who did the notes?” One of the junior execs said, “It was a team effort. They’re a little rough because we didn’t have time to polish them.” Katzenberg said, “You’re kind of throwing the baby out with the bath water, don’t you think?” He then threw the notes over his shoulder and said, “Let’s just make the movie.” He came over and sat with us and immediately started talking about casting. I wanted to hug him.

KJC: Is there anything I haven’t asked that you would like to say?

TS: Trust your gut. Leave your ego at the door and be open to suggestions and improvements, but fight for everything you believe in.

Kevin J. Cummins earned an MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. Born in Queens and raised in western New York, he has taught in Brooklyn, San Francisco, the Caribbean, and Albuquerque. He almost never tweets @kevinjcummins.