#VirginiaWoolf, #Instagram, and #Feminism

#ARoomofOnesOwn

I set out to make my home office a space where I could create. Soon, though, winning Instagram’s approval took over.

What would Virginia Woolf do?

Upon entering Antioch’s MFA program, I challenged myself to understand stream of consciousness technique and committed to reading lots of Virginia Woolf. Her lush descriptions of decor got me thinking about Instagram and its barrage of lifestyle imagery.

Woolf protested Victorian ideals—in particular, women remaining at home with no financial autonomy. So, I often wonder if she admired the cozy, sun-filtered domesticity her fictional female characters embodied or scorned it. And, with an eye toward modern times, I wondered:

Is our current portrait of aspirational domesticity, perpetuated by Instagram, antifeminist?

I guess I’m not the only one wondering what Woolf would do. In the December 2018 issue of The Writer’s Chronicle, Martha Cooley explores Woolf’s “Three Guineas” essay.

Cooley writes, “Here, it’s intriguing to imagine what she would have made of social media and women’s roles in their use. Would she have found Facebook or Instagram, for instance, encouraging or discouraging of intellectual liberty for women?”

Certainly, Woolf would have found the barrage of lifestyle imagery Instagram promotes distasteful and constricting.

Or would she?

Woolf wrote in her revised “Professions for Women” essay: “But this freedom is only a beginning; the room is your own, but it is still bare. It has to be furnished; it has to be decorated; it has to be shared.”

I think of my home office, replete with den-like cobalt blue walls, a built-in bookcase, and art pieces I’ve sourced in the last decade. When I quit my last corporate job to pursue graduate school and work from home for a family business, I vowed to make the space cozy but inspiring—a place to create. A room of my own, but to be shared with others—my husband when he curls up with a book in the corner armchair, our houseguests when they want to sit and talk writing process with me.

Critic Emily Blair points out that, in “Professions for Women,” Woolf again gives domestic interiors the power to “define feminine identity.” Blair writes, “the challenge is to refill the ‘bare,’ empty space with interior redecoration, and this redecoration includes establishing conditions, ‘terms,’ for how to manage social relations.”

#DepthinStillness

A tool to show off “redecoration,” Instagram establishes its own social constructs, from dinner parties to fitness lifestyles to pet ownership to parenthood. Many think pieces written in the past few years skewer Instagram’s high school popularity contest algorithms, its alienating and competitive nature, and its negative effects on our collective mental health.

In Woolf’s masterful, stream-of-consciousness domestic novel, To The Lighthouse, the Ramsay family summers in a Victorian home on a Scottish isle. The lighthouse on a neighboring island shines its consistent, rhythmic lumens on the Ramsays’ domestic life. This light-filled motif for consciousness is one Woolf returned to often, comparing life to a “semi-transparent envelope”—a “luminous halo”—in an essay entitled “Modern Fiction.”

Over and over again, Woolf demonstrated Mrs. Ramsay committing small physical acts within the confines of the Ramsay summer home. These routine acts signify a world of concurrent emotion swirling in Mrs. Ramsay’s head and heart. Even if Woolf revolted against domesticity in theory, her work championed the teeming brainpower of the women of her time, women who wielded power over their households.

Jambalaya in a cast iron pot, reminiscent of Mrs. Ramsay’s dish.

One look at the domestic life of Mrs. Ramsay, peering into her dish of beef stew, reveals a sparkling, warm charm.

After her son becomes engaged, a sensation rises in her “at once freakish and tender, of celebrating a festival…at the same time these lovers, these people entering into illusion glittering eyed, must be danced round with mockery, decorated with garlands.”

This scene could be the caption for a glowing kitchen in an Instagram post—an advertisement for a stylish cast iron Staub pot.

Mrs. Ramsay’s vivid, visual reaction to her son’s engagement also brings to mind the Wedding Industrial Complex that litters Instagram, clogging eager brides’ feeds with an aesthetically pleasing lifestyle that is nonetheless for sale: beaming young couples and Woolf’s decorative garlands, lovely and locally sourced flower crowns.

Woolf distilled the complex thoughts and emotions of Mrs. Ramsay—and of Victorian women in general—into singular, near-photographable moments. All readers living in an era over-concerned with capturing the gorgeous mundanities of life—the Instagram generation—should read Woolf. Without the aid of a #VSCOcam app or the benefit of a #paidcollab with Pottery Barn, without aspirational imagery, with her words alone: Woolf teaches the reader to recognize depth in stillness.

#CurrentDesignSituation

However, I do wonder if Woolf would get onboard with the amateur interior stylists that populate Instagram.

I love to nest and decorate. I moved around a lot when I was a child with my then-single mom, but I always craved the stability of an immoveable home. As an early technology adopter, I’ve been Pinteresting home décor ideas since 2009.

Despite my utter lack of interior design training, a love of vintage chairs in dire need of reupholstering, and a commitment to never paying full price for furniture, I aimed to impress my Instagram followers with my home designs. My husband says I have a furniture problem like he has a motorcycle problem—I always have to bring home the orphans. The just-a-little-broken ottomans and wobbly end tables.

I aim to create a space in which we can live, create, work, and entertain. The charm of worn wood furniture contrasted with new, gleaming appliances is an aesthetic of careful balance, modern but cozy, clean but a little bohemian, that I study in books and blogs and attempt to replicate in my home. Instagram at first seemed like a viable platform to display these efforts.

However, in the past two years, my commitment to gaining followers and “likes” on Instagram based on my interior decor reached annoying levels. In short, I tried to impress people I knew and didn’t know, and probably irritated everyone around me.

“Look at me! I own a home! Look at me! I installed a lamp!”

I am sure the “I’m better than you at #decorating” cattiness and conspicuous consumption—shoppable accounts, perpetual ads, paid designer/product collaborations—that Instagram breeds would not garner Woolf’s approval. She noted her anti-advertising sentiments in more than one essay.

Mrs. Dalloway presents a less troubling, more communal view of domesticity. Woolf projected Clarissa Dalloway’s party as Valencia-filtered images of domestic revelry—the charming, chiming brass clocks and pleasant tinkle of crystal; the beautiful, sharp Clarissa in her mended emerald dress; the spirited conversations between guests.

Photo by Stacie Flinner for MyDomaine‘s August 2018 feature, “How To Decorate Like Your Favorite Fictional Character.” This is an interpretation of a Mrs. Dalloway room.

For those with hopes of styling their own apartments or homes with whimsy, grace, and style, Woolf’s well-crafted words in Mrs. Dalloway are the literary embodiment of #DinnerParty, #AnthropologieHome, #KitchenGoals, #FoodPorn, and #DIYLife. Woolf was better at the language of aesthetics than Instagram ever will be.

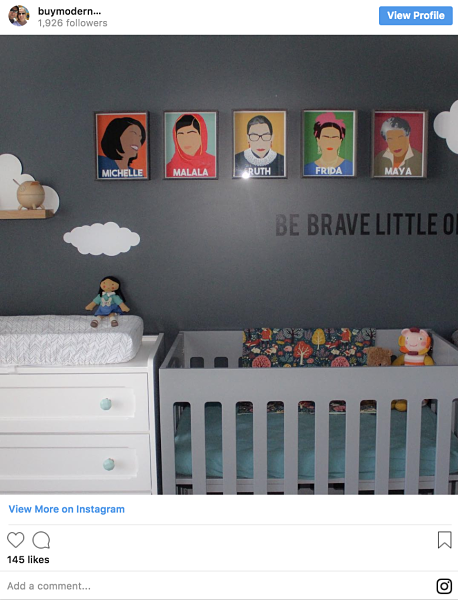

Instagram—or rather, the platform’s trove of buyable pastel “BOSS BABE” art—is photographic proof we live in a time when we can declare many lifestyles feminist, as long as we recognize the equality of all humans within their respective stylish spaces. I believe Woolf would find our world fortunate that, less than 100 years after the publication of To The Lighthouse, we can embrace both femininity and feminism in interior décor. The domicile is no longer a tool of female oppression, especially in a post-recession economy with flexible employers who, more and more, allow employees of all genders to sometimes work from home.

A domicile that, algorithms be damned, I still want to decorate, to adorn with kilim rugs and strategic, soft lighting, with mid-century modern furniture and fluffy shearling pillows.

Are we not supposed to want this prettiness? Am I a shallow, image-obsessed idiot? Am I a victim of consumerism-driven culture?

Maybe, maybe, maybe.

#TopplethePatriarchy

After seeing a few too many Instagram ads hawking unaffordable silk pillowcases and artisanal ceramics, I realized I was feeding into the system. Instagram’s algorithms track Likes and hashtags, using them to monetize user content, assigning users and their images worth on engagement, likability, and revenue-generating potential. The second I posted photos of home improvements to social media, the platform profited off my creative efforts and, frankly, my decorating expenditures. I spent money so Instagram could make money. Ad-busting Woolf would have been displeased.

I also realized I was not doing right by my fellow feminists. Instead of building women up, I pushed them down. Instagram doesn’t have a conscience about feeding our collective image obsession at the expense of its users’ psyches. Every styled corner and artistic tablescape I posted seemed designed, via the algorithms, to make other users self-conscious.

Even after unfollowing all the accounts that made me feel not fit enough, not hot enough, not hip enough, not enough of an artist, not a good enough cook, I would still welcome more of Woolf’s consciousness—that “semi-transparent envelope” or illumined halo of life—to my feed. I’d rather read captions accompanying stunning home imagery that reveal the true difficulties behind the photo shoot—the toddler vomited, the dress hem tore, the sink broke, the basement flooded. Better the long, real, raw story than the vapid and unconvincing:

#bestday #bestlife #blessed

Apartment Therapy featured this Instagram account in its March 2018 feature, “How A New Wave of Feminism Is Changing Decor.”

As I debated setting my Instagram account to private, I turned again to “Three Guineas,” in which Woolf advocated for an Outsiders Society, a pacifist, media-skeptical, women-led group. Members of this Outsiders Society should “increase private beauty” and “extinguish the coarse glare of advertisement and publicity.”

So long, paid Instagram accounts and Kardashian selfies.

Private beauty includes appreciation of the aesthetics of both nature and the domestic, Woolf wrote: “the beauty of flowers, silks, clothes…the scattered beauty which needs only to be combined by artists in order to become visible to all.” As long as Outsiders Society members reject fascism and the ornamentation that goes with it, Woolf implied we can enjoy all the leather bound books, sculptural objets, and just-because bouquets we want.

I’m relieved; I delight in decorating with fresh flowers and books with artistic cloth covers.

“… Woolf was way ahead of most of us,” Cooley continues. “She admonishes us to keep our eyes on actual power structures, on the real workings of domination.”

I see what Woolf meant. Ensconced in our chic blankets, we should call out publications that publish only cisgender white males. Using our quirky floral stationery, we must write back to a potential employer that asking whether we plan on having children is an inappropriate and illegal inquiry, designed to curb women from climbing corporate ladders. While sipping our French press coffee, we need to remain skeptical of our president when he says or does literally anything.

Fostering “private beauty” requires enjoying cocktails while perched on leather poufs atop pretty rugs in our living rooms, scheming with friends who also want to topple the patriarchy. We won’t take a single photo while we plan. Instead, we’ll appreciate the spaces we’re in, designed for our comfort rather than for consumption. That’s what I think Virginia Woolf would do.

The bedroom in Monk’s House, Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s former home in East Sussex, England. Photo by David Ross.

E.P. Floyd is lead blog editor and weekly content manager for Lunch Ticket, and an MFA candidate in fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her writing is published or forthcoming in Lunch Ticket, Litbreak Magazine, Reservoir, and BusinessWeek. She is at work on a novel and short story collection and lives in rural Wisconsin. Find her online at epfloyd.com.

E.P. Floyd is lead blog editor and weekly content manager for Lunch Ticket, and an MFA candidate in fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her writing is published or forthcoming in Lunch Ticket, Litbreak Magazine, Reservoir, and BusinessWeek. She is at work on a novel and short story collection and lives in rural Wisconsin. Find her online at epfloyd.com.