Back to School

Prayer Flags, Lama Foundation

Back to school arrives so early now—often weeks before Labor Day, the unofficial last day of summer. Thanks to my teaching schedule, which doesn’t begin until late September, and home-schooling history, I routinely extend summertime for my children. I teach summer school in July to fund late summer road trips. Instead of posing for pictures on the first day of school, my children filled the Jeep floor with sand and shells and rocks the summer we camped our way up the California coastline from La Jolla to Santa Cruz. They spent many summers-turning-to-fall high in the Rocky Mountains, fishing in shallow streams, hiking in alpine meadows, and throwing snowballs during freak summer storms.

Our trips became more complicated as my children opted to enter more formal educational programs, but not impossible. This year, my younger son, Parker will be taking an independent study in late September so that he can go to Spain with me and his big brother, Quentin, who is working until we leave. When school starts for my youngest child, Olivia, she’ll be with me, participating in life at the Lama Foundation, an intentional community in Northern New Mexico committed to ecumenicalism, ecology, and consensual decision-making. I expect Olivia will gain more from weeding and picking berries in Lama’s organic garden, helping to cook for the thirty-plus community members who will be in residence, and assisting with mud-plastering and other maintenance in keeping with her interests and abilities, than she would in any classroom.

* * *

Earlier this week, as Olivia and I neared Flagstaff, our first stop en route to Lama, I remembered another August road trip through Arizona. At dawn on the first day of school in 2011, all four of my children and I climbed into our fully loaded Honda Pilot for the final leg of our trip home to California from Dubuque, Iowa. We’d made the almost cross-country journey there to attend my youngest sister’s Midwest wedding reception and baby shower.

About the time we crossed the New Mexico-Arizona border, Parker, then a sixth grader, began an oral reading of the final three pages of the history textbook I’d assigned for the year. He intentionally projected his naturally loud voice from the third seat so that we wouldn’t miss a thing up front. I was excited to find out just how Story of the World author Susan Wise Bauer would sum up the 1991 Persian Gulf War. His siblings were not so enthusiastic.

“Please…I can’t work with him talking,” Quentin said.

Quentin, returning to public high school as a senior that year, was in the passenger seat completing notes on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment due his first day back in school.

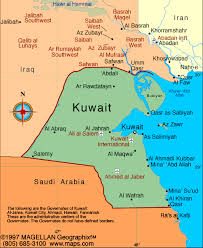

Kuwait’s geographic location

“Mom…The people in Kuwait were so lucky…They didn’t have to pay any taxes, and the government paid for their school…but not anymore,” Parker said.

“Yeah,” I said. I explained that the only Kuwaitis I ever knew were students traveling in Southern California. “They left a $100 tip for a couple rounds of beers during Monday night football at the bar where I worked.”

“No way!” Parker said.

“When did you go to Kuwait?” Reiley asked. She was starting public school as a freshman that fall and must have been really caught up in her summer reading: The Odyssey.

“I didn’t go to Kuwait. I served drinks to some guys from Kuwait,” I said.

The kids wanted to hear more about the Kuwaitis, but were distracted by the first roadside directions from on I-40 to the meteor crater southeast of Flagstaff, AZ. “You were supposed to take us to the meteor crater,” Parker said.

“You’ve been there,” I said. “You were really little…”

Meteor Crater, Arizona

“What’s a meteor crater?” asked six-year-old Olivia.

“A big hole in the ground where a meteor crashed into the earth,” Parker said.

“What’s a meteor?” asked Olivia. She leaned forward in her seat, clearly concerned.

“Like an asteroid…” Parker began.

“You know how the earth goes around the sun? Well a lot of other things, like much smaller rocks, also move in space, and sometimes they collide with the earth,” I said.

Quentin helped move the conversation well away from “asteroids crashing into our planet” by turning around in his seat to face Olivia and using his hands and cell phone to illustrate the movements of the earth, sun, and “aster…I mean rocks” in space.

Unwilling to be left out, now that we’d distracted her from Odysseus’s trials, Reiley interjected a summary of the theory that an asteroid killed the dinosaurs.

Fantastic. She just had to add death to the mix, I thought.

At the time, Olivia was obsessed with the various ways she might die. I was nowhere near prepared for one of her prolonged crying jags over the possibility that she would be destroyed, along with much of the surrounding desert, by an asteroid before she could be reunited with the daddy she couldn’t stop telling us that she missed so very much.

“Rocks and other debris from space are usually really small by the time they reach the earth,” I said.

“Yeah, they burn up in the atmosphere,” Parker said.

“Now meteors are so small they just hit you…they don’t make gigantic holes in the ground…” Olivia said.

“Right.”

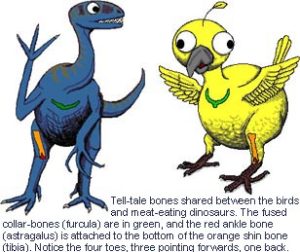

I thought we were done. Then Reiley said, “Except the one that killed the dinosaurs.” Thankfully, she didn’t stop there, but went on to tell us how dinosaurs are related to birds so that, according to an article she read in Science, chickens are kin to Tyrannosaurus rex.

I thought we were done. Then Reiley said, “Except the one that killed the dinosaurs.” Thankfully, she didn’t stop there, but went on to tell us how dinosaurs are related to birds so that, according to an article she read in Science, chickens are kin to Tyrannosaurus rex.

I pulled off the highway in Flagstaff just after convincing Olivia that relationship between birds and T. rex did not mean that our neighboring chicken farm was likely to produce miniature dinosaurs. Or so we thought.

“If the little dinosaurs come to California, we could just move to Colorado,” she said.

* * *

Like that car-bound lesson on history, astronomy, and paleontology, most of my best memories have been unexpected. My only objective was to enjoy the ride with my children and arrive safely in Flagstaff. I trusted my children would grow from the experience, and that would be enough. My strongest writing often occurs the same way. Writing is hard work. Still, each time I begin to write, I intend to enjoy the process as much as I expect to survive it. I trust that I will grow from the practice of writing, and the words I select and arrange on the page will approach art.

* * *

“I can’t believe I ever thought dinosaurs came from chicken eggs,” Olivia says. She’s looking over my shoulder now as I write.

Today, we toured Earthships in the Greater World Community outside Taos, New Mexico, about thirty miles from Lama. Earthships are homes constructed from natural and recycled materials to ensure ambient temperatures, conserve water and energy, and provide most of residents’ food. Olivia was entranced. Afterward, we enjoyed a late lunch at the Taos Mesa Brewery that included an English ale for me and a bottle of root beer for her. Olivia insisted on saving the bottle to use when she builds her own Earthship.

Model Earthship with Bottle Artwork

Juliann Allison is a feminist scholar, environmentalist, homeschool advocate, yogini, runner, rockclimber, mate, and mother of four with a passion for the outdoors. She is Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and Public Policy at UC Riverside, and an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles.