Why American Dirt Matters to All of Us

Braceros on railroad tracks, Arizona, 1944. (Photo Credit: Aaron Castañeda Gamez via Smithsonian Institute)

My friends and I are still reeling from the news of American Dirt, that pinche novel written by Jeanine Cummins, rolled out by Flatiron Books as the next Grapes of Wrath, and then chosen as the January selection of 2020 by Oprah’s Book Club.

People all over the world are buying American Dirt, reading it, and declaring it to be an “eye-opening” piece of literature. Friends in other countries have seen it in bookstores, and are told it’s a book about the US/Mexico border and immigrants fighting to stay alive as they cross it. It’s not. It is, for all intents and purposes, cultural appropriation in a book. It is brown-face. It is cliché and generalization, and what newspaper-reporters used to call sensationalism.

This isn’t just about the author of Dirt. Cummins identifies as a white woman, explaining in a New York Times essay, “I am white….in every practical way, my family is mostly white.” I know plenty of white people who understand the intricacies of Mexico and immigration, but judging from her book, Cummins isn’t one of them. This isn’t just about Oprah’s Book Club, or Oprah, who saw a rough draft of Cummins’ book last year and somehow decided it would be a good selection for OBC January 2020. This isn’t just about the industry: Flatiron Books, a publishing arm of Macmillan, who celebrated this counterfeit piece of pulp like cheerleaders in front of a crappy football team. This is really about all of these things tangled together, like a bowl of fish hooks, too time-consuming and painful to detangle. It’s about gatekeepers and fair representation, and who has the right to tell our story. It’s about literary injustice, which affects all of us.

Before we go any further, I should tell you that I have Mexican and Irish heritage, the granddaughter of immigrants on both sides. I grew up with an Irish-American last name—my father’s heritage is Irish, and his family settled in Boston—but surrounded by Mexican-American culture. My Dad was in his early twenties when he moved to California and met my mom, whose parents were born and raised in Mexico. Dad and Mom married, had five kids, and stayed in California. Because we were surrounded by my Mom’s family, I felt most connected to that identity. Growing up in the San Joaquin Valley, there were plenty of others like me: mestizaje, or mixed races. My siblings and I had a typical mestiza (mixed race) identity. Because I was lighter-skinned, and because of my surname, I was often told that I wasn’t a real Mexican.

***

When I started reading American Dirt, I wanted to like it. I really did. I wanted to like it so much that I didn’t read the author’s note—one of my best friends read it before me, and it infuriated and insulted her—and began the first chapter. Spring-loaded with clichés that flew around faster than the bullets, the narrative lacked any authentic Mexican flavor. Wooden characters, like actors in a 1950’s black-and-white movie, clomped around in Ms. Cummins’ version of Mexico. Gun violence erupted at Cummins’ version of a Mexican family gathering, followed by an investigation by her version of the Mexican police. There was action, blood, and suspense, but the kind a sixth-grade boy might write. I made it to page nine before I jumped to the Author’s Note.

Cummins explained why she wrote the book, listing statistics of injustice and her husband’s immigrant status. She openly wishes that “someone slightly browner than me would write it.” Responding to the insidious prejudice of colorism, I wanted to scream: “It’s not about color! My skin is as light as yours!” She also claims her purpose is to act as “a bridge” between immigrants and readers, some of whom might consider immigrants as “the faceless brown mass” knocking at their door. There’s color again! But this time, she’s posing as a white savior, sent to speak for darker people, and deliver them from the white gaze.

In reality, Cummins wrote this book because she’s a writer, and that’s what we do. Her publishers bought and sold this book to make money. The astronomical advance paid out to Cummins is usually reserved for authors who write bestsellers, and Flatiron bet on Cummins like they knew they had a sure thing. The publishing industry predicts which books will sell and when, whose endorsements will be needed to sell it, and where it should appear for its audience to begin talking. Cummins worked in publishing ten years before she was an author, and knew the game well. She watched for the trend, applied a standard business formula to a social justice cause, and viola! American Dirt. Flatiron bought the book, and sold it to us as “the ordeal of a mother who escapes the violence of Mexico with her son, and enters the United States as an undocumented immigrant.” A book is a team effort, so Cummins, her agent, and her publisher added the finishing touches to present the reading world excitement, romance, and life and death on every page. If I were reviewing, I’d say it reads like a Narcos rip-off, with a little bit of romance mixed in, peppered with some google-translated Spanish and phrases to testify of its authenticity. For me, the book wasn’t worth finishing.

At the release party, Flatiron Books arranged for centerpieces to resemble the border wall, complete with barbed wire.

Publishers had a bidding war for American Dirt, this counterfeit story, this misrepresentation of Mexico, Mexicans, Mexican families, and our immigration process. Flatiron Books reportedly shelled out a seven-figure sum (Cummins later denied this). The partnership between Oprah and Flatiron almost guaranteed a book club selection, supported by an extraordinary amount of editorial attention, marketing, and publicity. Oprah selected it, and promoted it in every social media venue. She gave free copies to her famous Latina friends and asked them to endorse it. She made TV appearances. All of this guaranteed the book a global audience. After all, this is Oprah!

It was like a knife in my heart, not just because Oprah chose this book, but because she was our hero. How could a woman of color, one that got the whole world reading, not see what was happening? Didn’t she read the book? Didn’t she see this was all so fake?

These wounds were salted by American Dirt’s cover blurbs by Stephen King, John Grisham, and one of my favorite authors, Sandra Cisneros. Don Winslow called it a “Grapes of Wrath for our times.” Even reviews were whitewashed, like a scene from The Twilight Zone. The New York Times, NPR, The Atlantic, and most national magazines didn’t ask a Chicana, or any Latinx writer, to review the book. There was DEFINITELY a shortage of Chicanas vetting the book in Oprah’s Book Club, because most of us stopped reading in the first few pages, since we could see, feel, and smell the rip-off of our story, our people, and our culture in the first pages.

It unearthed a cold reality: a lack of Latinx representation, specifically Mexican-American representation, in most literary circles and publishing empires. The scarcity of Latinx authors, reviewers, and agents is seldom talked about, but can no longer be denied. In 2018, Publisher’s Weekly estimated that the publishing industry only has 3% Latinx working in the industry. The lack of Mexican-American representation in the industry is killing our voices off.

***

After Oprah announced her Book Club selection, the proverbial shit hit the proverbial fan. The Latinx community came together and pointed out that Cummins was guilty of brown-face. Esmeralda Bermudez for the Los Angeles Times wrote: “Never in nearly two decades of writing about immigrants, have I come across someone who resembles Cummins’ heroine, a Mexican woman named Lydia.” Myriam Gurba, author of Mean, published her scathing review of the book, aptly titled, “Pendeja, You Ain’t No Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature,” published on Romeo Guzman’s literary/historical website, Tropics of Meta. . Gurba said it for all of us: “Unfortunately, Jeanine Cummins narco-novel, American Dirt, is a literary licuado that tastes like its title. Cummins plops overly-ripe Mexican stereotypes, among them the Latin lover, the suffering mother, and the stoic manchild, into her wannabe realist prose.” I was fist-pumping before I could finish. Gurba’s review went viral, and she along with literary fellows, David Bowles and Robert Lovato, assembled a literary strike-force of sorts, #DignidadLiteraria. Suddenly, we were all alive on Twitter.

After a few days of Latinx protest (imagine all of us calling bullshit from social media and all of our websites), Bob Miller, the president of Flatiron Books (publisher of American Dirt) tweeted a public statement/apology. At first, his letter looked promising, but Miller began to show his impatience. “We wish to listen and learn and do better. But that also must include a two-way dialogue characterized by respect.” Miller’s statement reminded me of Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” where a manipulative speaker tries to convince a girl that getting screwed by someone with a little power is better than dying a virgin and having your corpse get raped by worms. If the president of a publishing company can point his finger in the face of a million chingonas, and tell us what “must” happen to have dialogue, and use the word “respect” like we started this whole thing, can he really call it an apology? American Dirt is an act of disrespect toward the Latinx community. How could they not see this reaction coming? It made me wonder: was the whole media frenzy really accidental? Or was this all just free publicity?

***

Grandma, Aunt Terry, Uncle Frank, and Grandpa

My maternal Grandparents (I capitalize that noun) each fled Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. They came into this country, where they were contracted to work the earth. In their seventies, their hands were wrinkled maps, and their gnarled knuckles told the stories of work and work and work.

By the end of this year, I will have compiled our family stories, including their stories of immigration, into a memoir. It will document the true and dangerous road of immigration for ourselves and our posterity. I have a dream of publication for this memoir.

Despite war, starvation, graphic violence, and painful memories, my Grandparents always considered Mexico their homeland. They always met with and prayed for the new immigrants coming over. Grandma’s rosary was a worn stretch of beads, always praying for those who stayed behind. They passed on the love and joy of it to us, and asked us to remember our heritage. We are Mexican-American, and our stories are passed down by way of the oral tradition. They take longer to gather and place side by side. Over time, this collection of stories becomes authentic.

If an author wants to write a personal story about a family from another culture, they might be able to fool some, but probably not someone from that culture. If their story is based on observing others, rather than their own their own heart, their story will be counterfeit—a copy of something real, but not real itself.

How do I know this? I did it myself–with the best of intentions.

***

Like Ms. Cummins, I once wrote a novel about another culture, hoping it would be a tribute to them. In all fairness, the idea of cultural appropriation wasn’t as real to me as it is now. Back then, I was all about writing the book.

I lived in South Africa for seven years, among the very poor, and built life-long friendships with women who confided in me daily. They had great joy, and great struggles. Their faith was amazing, and I loved them. We worked side-by-side for seven years, and as I neared the end, I asked them if I could write about them. They agreed, provided that the book I write be fiction. They made me promise not to use their names. They read chapters from the rough draft, and helped me with phrasing in seSotho or isiZulu.

When my husband and I left Johannesburg in 2013, I had my finished novel in hand. My agent was enthusiastic, and began to send it out. It never sold. I now know that my novel really wasn’t my story to tell. Back then, it was a bitter pill to swallow, but now I think it might be a blessing. My failed novel now lives, happily, in a box behind my desk. It’s a reminder to have the guts to write my own necessary stories.

I’m sure Oprah’s Book Club would have never considered my novel as a selection, even if it was published. After all, it was written by me, not by someone from the Zulu, Sotho, Xhosa, or Ndebele culture. Sure, I knew a lot about the people and their ways, but I was never one of them. I never felt the things they wouldn’t tell me. Even though I saw my novel as a love-letter to the powerful women I left behind, Oprah’s staff might not. She has plenty of savvy Black women vetting these selections, and they would have put my novel down after nine pages. I don’t think my good intentions would matter, because the road to hell is always paved with them.

***

I posted on Instagram, responding to Oprah’s open call for a forum of positive conversation. Later, I received a message, then an email from one of her staff, a program coordinator from Oprah’s Book Club. It was real. It was legit. I was excited to get it.

“We’re currently preparing for our upcoming episode about American Dirt. As part of the show, we’re working on a piece that features a variety of reactions to the book. I saw your post and wondered if you would be interested in participating? If so, please let me know and I’ll provide more details.”

I wrote back, accepting the invitation, but I wasn’t a puppy. “I’ll participate if I am USEFUL, but I don’t want to be used. The difference in media today is astounding. We feel bitten by this OBC selection, so naturally Latinx writers are shy to enter the arena with the one who bit us. BUT this is a discussion that needs to happen.”

The coordinator wrote back:

“I completely understand your concern. We want this to be an opportunity where all voices are amplified and that is why I was really struck in a great way by what you had to say.”

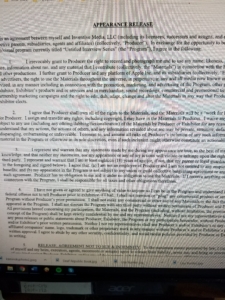

Part of the contract from OBC

Flattered, and a little excited to participate in Oprah’s conversation, I began the process. Then, they sent me a contract. I read it all. My recorded voice would be hereby be referred to as “the Materials” and these “Materials” would become the property of Inventive Media LLC, Apple Inc., and all its subsidiaries. They would have the irrevocable right to use “the Materials” in any way they chose in marketing campaigns. They would also have the right to “edit, dub, adapt, change, and alter the Materials” for their purposes. In other words, they would own my voice and my words. For some reason, this made the whole thing real for me. I had a choice to make a difference, to be heard by Oprah (It won’t cost much, just your voice), and participate in a meaningful conversation. Then again, why hadn’t she removed the book from her Book Club list, like she had with James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces?

Was this really a discussion to make a difference? How about no?

***

The journey from Mexico to los Estados Unidos is complicated, and filled with authentic story. Generations continue through story. Our family memoir is one of these, slow-cooked by my family for five generations—because immigration is a generational story for any culture. If I happen to sell this memoir and make one-half of one percent of Cummins’ advance and profits, I would be happy. Even greater, I’d like for others to read it. It is my necessary story, the one I wrote using my own authorial voice.

My Grandparents passed on their dreams of finding significance, here in the United States, to me. After their life of tilling the soil and raising successful crops, they rested, their dreams never fully realized. I still carry their authentic stories in my heart, their fragrance and flavor are always with me. My own version of their American Dream involves the publication of their story, the one given to me as a treasure, passed on through the oral tradition. I hope our story is read and recognized as significant. If I’m honest, my dreams include Oprah’s Book Club and the New York Times.

For Latinx writers, our words are our children, going out to the world, hoping for acceptance and recognition. With American Dirt, the publishing industry pushed our books aside, chose a rip-off of our story, and sold it to the world as real. Oprah’s endorsement of Cummins was like a parent pushing aside their hardworking child in order to praise a privileged one for stealing from their sibling. Consumers that buy American Dirt applaud a brown-face performance, and admit they don’t know the difference between a genuine or counterfeit story of Mexican immigration.

***

On February 3, representatives for #DignidadLiteraria met in New York City with officials from Macmillan, the parent company of Flatiron Books, which published American Dirt. It was there that David Bowles read a statement that Macmillan had agreed to transform publishing practices to increase Latinx authors, books, and staff. During the meeting Macmillan committed to developing an action plan to address these goals within 90 days.

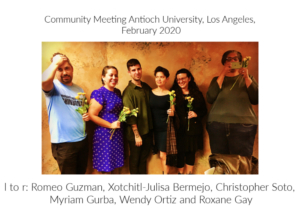

Two days later, Antioch was the site of a community discussion organized by Women Who Submit, where a standing-room-only audience discussed the issues surrounding Latinx Literature and telling our own stories. Our distinguished panel included Romeo Guzman, Xotchitl-Julisa Bermejo, Chris Soto, Myriam Gurba, Wendy Ortiz, and Roxane Gay. It was a magical time.

Janet Rodriguez is an author, teacher, and editor living in Northern California. In the United States, her work has most recently appeared in Eclectica, The Rumpus, Cloud Women’s Quarterly, Salon.com, American River Review, and Calaveras Station. She is the winner of the Bazzanella Literary Award for Short Fiction and the Literary Insight for Work in Translation Award, both from CSU Sacramento in 2017. Currently she is a Cardinal MFA candidate at Antioch University, Los Angeles, where she serves Lunch Ticket as Managing Editor.