Wobbling With The World: An Interview with Chen Chen

The poetry girlies, myself included, love Chen Chen. We can’t help ourselves. With a fashion sense that slays (mixed prints, yes please!), an endless array of savage tweets (“sigh. last day to be a queer poet. tomorrow i go back to being a straight tax accountant who only reads the wall street journal”), and poetry that can turn any hater into a lover, Chen invites us all to celebrate living our best authentic lives.

The poetry girlies, myself included, love Chen Chen. We can’t help ourselves. With a fashion sense that slays (mixed prints, yes please!), an endless array of savage tweets (“sigh. last day to be a queer poet. tomorrow i go back to being a straight tax accountant who only reads the wall street journal”), and poetry that can turn any hater into a lover, Chen invites us all to celebrate living our best authentic lives.

While studying under his mentorship at Antioch’s MFA program, I shared my insecurity of being seen as “too strange” in my writing. Without hesitation, he encouraged me to lean into my weird—words I was waiting to hear all my life. That was when I became the ultimate fangirl.

Doesn’t everyone seek this level of validation from a mentor, whether teacher, parent, or otherwise? It’s truly a gift, and Chen knows that. In his books Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency and When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, both published by BOA Editions, Chen courageously shows us all the ways he’s ever felt different. But from being different, or weird, or “ a freak” (to quote another tweet), he’s made a path for himself, one where he’s successful at doing what he loves.

When I spoke with Chen Chen on Zoom at the end of August, we discussed topics such as the embarrassment of being a writer (especially a poet), and how activism and community both play roles in the written word. We also talked about cats, because, why not? The interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Jessica Ballen: When people ask what you do for work, do you say you’re a professional poet?

Chen Chen: I usually say writer or teacher, and then they ask me what I teach, and I say writing. And then they say: what kind of writing do you teach? And then I say poetry. It’s a multi-step process to get me to say poetry even though it is the genre that I primarily work in and that I care about the most. I can talk about it for ages but there’s still something that feels a little embarrassing. Elizabeth Bishop famously said there was nothing more embarrassing than being a poet. There is something weirdly antiquated sounding even though I know so many living contemporary poets. The art form is well and alive, and yet, to someone who doesn’t know that and doesn’t read or think about poetry on a regular basis, it might seem like, oh, you’re still doing that? I don’t know, maybe I need more practice just being comfortable with saying yeah, I’m a poet. I teach poetry. It’s my life. But still, honestly, it takes a moment, and they have to almost pry it out of me in conversation.

JB: I wonder if past experience has traumatized us a bit? Plenty of people have asked me “What could you possibly do with poetry?” Maybe there’s a level of protection, trying to keep our identity safe, as a result?

It is this kind of secret thing, or it can feel like that because it comes from such a private or vulnerable place. So it feels weird to say that that’s your profession. Published work is obviously out there in the public, but where the writing actually comes from is private.

CC: Absolutely. It is this kind of secret thing, or it can feel like that because it comes from such a private or vulnerable place. So it feels weird to say that that’s your profession. Published work is obviously out there in the public, but where the writing actually comes from is private. It can feel funny to reveal that, especially with someone you don’t know or that you’ve just met, even though it’s a very normal question.

JB: Speaking of vulnerable places, did you feel accepted as a creative, queer person growing up?

CC: My family, my parents in particular, have become more accepting and understanding when it comes to my queerness, thankfully, but they’re having a harder time accepting that I’m a writer now, which is unexpected. I thought it would be the other way around. In any case, they had incredible difficulty accepting either of those things in my life. In navigating their disapproval, I had to seek encouragement and support from other people, whether those were peers or teachers. When it came to being a writer, it wasn’t that my parents were against the arts or creativity in any way. I think they were just worried, as many parents are, about financial stability, and so they were really pushing me to pursue something that would guarantee my financial future, like becoming a doctor, or a lawyer, regardless of whether or not I was personally interested in it, because it’s not really about that. And this is true maybe especially of immigrant parents, but probably parents across the board—in their minds what you’re personally interested in is separate from what your career path should be. Sometimes I’ve wondered if I should have had more of that mentality, because there are days when it is frustrating for it to be all combined, where my personal passion is also my career. For some people, in a very romantic sense, that’s ideal, right? You do what you love, but it’s like, do you want to do what you love all the time for money and for external things? You put so much pressure on this art that is really beautiful and meaningful to you. So there’s also a part of me that can see where my parents come from, not so much from a financial standpoint, but how these things need to be separate for you to have a balance in life. But I don’t know, maybe I’m just too obsessive for that—I just have to be monomaniacally focused. It’s very fortunate that it has also become a viable career path for me.

JB: How do you keep the business side of poetry separate from the creative?

CC: I’ve thought about having hobbies, but I’m just not as interested in other things. Does watching TV count as a hobby? I’m always thinking about writing in one way or another. When I was younger, there was a point where I thought about becoming a TV writer, so that’s very much connected as well. I’ve always enjoyed that format of serial storytelling, where you can follow characters for multiple episodes, multiple seasons, although these days, or maybe it’s always been the case, a lot of shows don’t make it past that first season. But I love that form of storytelling. I feel like things that might count as hobbies are also pretty closely related to my interest in writing, and that’s just how I like it. Sometimes I think it would be nice to get really into knitting. There were times when I’ve done very basic kinds of painting, and I like watercolor paints a lot, but it’s never been as regular an interest or practice as writing.

JB: I enjoy painting as well, but I play out the steps that I need to get there, and it’s just easier to pull out my phone or just sit down at my laptop or take out my journal, whereas, with paints, I have to set everything up and figure out a way to keep the cats from knocking the paints over.

CC: It’s a different process.

JB: Right, it’s a different process.

CC: I guess to actually answer your question, of what happens when writing is so enmeshed with everything else and finding balance, what’s been important to me is trying to make time where I’m really writing for myself, the way that other people might sketch or doodle, or how artists who have a sketching practice. It kind of feels like that. So I do that a lot, and it’s not with the aim or the direct, immediate goal of drafting a poem. I just think of it as notes, and it’s for myself, and that gives me a lot of joy. It feels like there’s a kind of purity to that. I don’t put any pressure on it to become anything someone else is going to see or publish. There’s something just in writing, just in the act of it, the process of it, that’s for me, and just comes out of my love for it. Then there’s the other side of poetry when the poems find their readers. I also love that deeply, but that is a different thing.

There’s something just in writing, just in the act of it, the process of it, that’s for me, and just comes out of my love for it. Then there’s the other side of poetry when the poems find their readers. I also love that deeply, but that is a different thing.

JB: This actually makes me think about Instagram poets who constantly post their poetry and how depleting that must be for them. Since you’re a poet who happens to use Instagram, do you think the two, poetry and social media, go hand in hand?

CC: I tend to think of them as separate things, because Instagram, social media in general, is this public-facing thing, and it is curated, though I try not to be too strict about what or when I’m posting because it’s not like monetized or anything for me. It’s for fun. It’s a way for me to stay connected with a bunch of people that I don’t get to see regularly in person, and it’s a way for me to find out about new books and new poems being published in magazines. And to look at cute cats. It’s very different from the writing, as I said earlier, with saying that my profession is poet, and how funny that feels because it’s rooted in something private, so I think the poem writing comes from a different place, which is not to say that there aren’t overlaps sometimes. I have had tweets that turned into poems, though it’s not like that happens every day. I don’t know. It’s a funny distinction, and sometimes it’s more nebulous.

JB: Do you compare yourself to other poets, and how do you deal with those feelings?

CC: I definitely do. I think that’s normal and unavoidable. Sometimes that just means it’s time to stop looking at my phone. But then it is also a choice to dwell in that. So if I can kind of extricate myself, that’s good. And I probably need to put down my phone, anyway, when those feelings linger. What tends to help, is either doing something completely different, like going for a walk or watching an episode of a show, or to actually read something by that person, by that other writer that you’re jealous of. Often I find that actually pretty helpful, because either I realize that I don’t really like their work—not that it’s not good, it might be really good. It’s just not for me. So then I’m like, oh, this exists for other readers, and that’s wonderful. Or, it is something that I love. And then actually, that love kind of cancels out the jealousy. I become a fan instead of a hater. So yeah, I think there are all sorts of ways to get out of that funk. And I’ve found reading to be a great way to do that.

JB: What is important in poetry for you?

CC: I want the language itself to be an experience. To me, that means more than just beautiful language, although I also love beautiful language. But I mean, language that is highly emotionally and intellectually charged. I love when a poem can make me feel and think at the same time, make me think about my feelings in new ways. It can make me feel my thought process in new ways. I want to be surprised by the language, but also by the turns in thinking, the shifts in tone, the changes in expression. I want to look up from the page, or if I’m just listening to the poem, when I’m done, to look at or to be in the world in a different way, and it could be just a slightly different way. It doesn’t have to be life changing, but to just feel like something in the room, something in the air has shifted a bit. I love that sensation where the world becomes a little strange again and kind of wobbles and you’re wobbling with it. Another important element is mystery, or room for mystery, room for wondering, room for questions, those moments where a poem opens up and feels really spacious. Then, as a reader, I get to enter the house of the poem, so to speak, and be in a different room all of a sudden, a room that I didn’t think was going to be there. And deep questions arise that are, by their nature, unresolvable. But then that also feels like life. So, I love returning to certain poems that have those really big, unexpected moments of mystery. It feels like a kind of generosity, like this gift that the poet is giving you, where it’s like, oh, life has more rooms than you thought it did, and you get to sit in them for a while.

At the same time, the poems are reflecting on the role of language, the failures of language alongside the failures of politics as usual in addressing such violence, and there’s also all of this space and generosity, these moments of existential and cosmic mystery in the poems.

JB: “Life has more rooms than you thought it did.” I love that. In terms of varying spaces, or rooms, poetry can be indulgent and hedonistic but it can also be rooted in activism and something more purposeful. Do you find yourself reading poetry like that?

CC: Definitely. I go through different periods, which I think is a common phenomenon among writers. Your tastes or interests shift or expand or refocus, in response to the political world that you’re always in. I’ve been slowly making my way through Fady Joudah’s new book, […]. He’s a Palestinian American writer based in Texas who is also a physician, and he has lost many, many family members in Gaza, and the poems are reflecting on the enormity of that loss, and the US involvement in Israel’s genocide of Palestinians. At the same time, the poems are reflecting on the role of language, the failures of language alongside the failures of politics as usual in addressing such violence, and there’s also all of this space and generosity, these moments of existential and cosmic mystery in the poems. So to me, there might be a tonal difference, and obviously, a difference in subject matter from other books that I’ve been reading, but it’s poetry, through and through. And another way it’s political is how the writing expands and questions and upends what poetry can do, as the best poetry does.

JB: How can a poet make a difference right now?

CC: For me anyway, it involves really listening to those who are affected firsthand or who are closer to what’s happening and doing what I can to amplify their voices. Taking their lead in terms of activism and strategy. The other big thing that comes to mind is in teaching: Talking about the work of Palestinian poets, sharing their poems, discussing them while also being mindful of not tokenizing. And not just teaching the work when there is the most apparent crisis unfolding, and not only teaching the work that speaks directly to that crisis. Thinking more holistically about each poet’s work and making sure to talk about the whole body of work and different kinds of subjects, different formal approaches, and how they’re situated in the larger history. So in teaching, that’s where I see a lot of my responsibility and a lot of my potential to contribute something meaningful.

I also encourage everyone who’s a poet or a writer of any kind to read and sign this letter, “Refusing Complicity in Israel’s Literary Institutions.” And if you can, to donate to a campaign on Gaza Funds. And to organize with, protest with, learn with your local activist groups.

JB: I’m going to switch gears slightly, but on the topic of teaching, there are obvious pros for a poet to pursue academia (like teaching opportunities), but there are a number of poets that don’t take that route. What can those people do to build their resume and how can they become a professional poet without academia?

CC: I think being engaged, however that makes sense and is accessible to you. So that could be on social media, following accounts of writers that you like, and also

publishers or organizations, and finding readings or workshops that you would like to attend. Many readings are free and open to the public. When it comes to classes, I would keep an eye out for ones that are free or sliding scale, or on the more affordable side, and are taught by poets that you admire, but are also on subjects or themes that really interest you and might be related to a current writing project or something you envision doing in the future. So yeah, it can start from a pretty modest place, and just letting your interests guide you.. I would apply the same approach to any in-person activities (again, if it’s accessible for you). Look for community workshops in your area. They could be affiliated with a school or run by a community center. Just let your interests guide you and see what is immediately available, and go from there.

JB: That makes sense. I try to think about accessibility because I do know a lot of people who aren’t in academia that write poetry, and I just wish it was more accessible for them.

CC: Yes! I also encourage more poets in academia to teach or do readings outside of that world, to offer what they have to offer to more people. Because, I think, that’s also part of how poetry can really grow.

JB: The poetry community is so important, and it shouldn’t be divided by who’s in academia and who’s not. We should all be in this poetry world together. Anyway, thanks so much for talking to me today, Chen.

CC: Thank you, Jess!

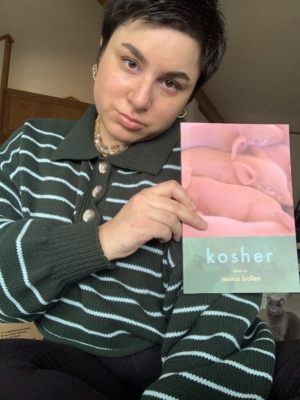

Jessica Ballen is a disabled poet who’s currently completing their MFA in creative writing at Antioch University, where they serve as Editor in Chief of Lunch Ticket, the school’s literary magazine. They are also a guest editor for Frontier Poetry. Their work can be found, or is forthcoming, in Ghost City Review, Wild Roof Journal, and Harbor Review, among others. Their book Kosher was released in early 2023 (Pine Peak Press), and you can find them compulsively posting on their Instagram stories @_j___esus. Ceasefire now!