Writers Read: Kingdom Animalia by Aracelis Girmay

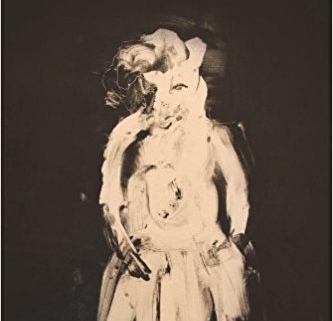

This collection of poetry opens with epigraphs by Charles Darwin, including one that lists similarities in the “framework of bones” between different animals: fins and hands, vertebrae in giraffes and elephants, “and innumerable other such facts, at once explain themselves on the theory of descent” (11). The poems shift their subjects from animals to humans, self to ancestor, often in the same poem. Collectively, they catalogue kingdoms that share the same emotive bones: the search for identity, passed-down family memory.

This collection of poetry opens with epigraphs by Charles Darwin, including one that lists similarities in the “framework of bones” between different animals: fins and hands, vertebrae in giraffes and elephants, “and innumerable other such facts, at once explain themselves on the theory of descent” (11). The poems shift their subjects from animals to humans, self to ancestor, often in the same poem. Collectively, they catalogue kingdoms that share the same emotive bones: the search for identity, passed-down family memory.

The collection is divided into six sections: “a book of dirt,” “a book of beautiful monsters,” “a book of graves & birds,” “a book of erased cities,” “a fable,” and “the book of one small thing.” The last two sections contain only one poem each: “a fable” contains the poem “On the Shape of the Sentence,” a longer poem that plays with typeface (strikethroughs and italicization) and layout as it travels through the Edenic image of the letter “S” as snake. Then Girmay traces letter shapes and images to spell out the word “She”: “She: / What would turn the curve of the S into the embryonic: e? / Evolution in words, in the progression of the line as it travels through the / silence” (103). As the poem keeps spelling subsequent letters and excavating the images therein, it moves through images of Cyclops, and then of the aunts of the girl (the poem’s subject). They comment on the girl’s shape, and the girl talks back. The words being spelled ultimately are: “She is my she” (107). This fable is about coming to terms with oneself: “She stands on both sides of the mirror, twinned, filled with grief for the / years she spent carrying herself around like a poison or a secret & elated / for the fact of surviving her face & shape for this minute of seeing / her all-selves—without an urge to kill or be killed” (107).

In “a book of graves and birds,” there are several poems titled as self-portraits: “Self-Portrait as the Snail” (52), “Self-Portrait as the Snake” (59-60), “Self-Portrait as the Airplane (Ode to Noise in the Ear)” (61-2), “Self-Portrait as the Pirate’s Gold” (65), and “Self-Portrait as the Snake’s Skin” (66-7). The animals of Girmay’s kingdom animalia are her selves. From “Self-Portrait as the Snail,” the poem’s speaker likens herself to a snail, with a trail of blood: “The things I’ve been marked & been marked by, / blood falling behind me like a stranger’s tail” (52).

The animals of Girmay’s kingdom animalia are her selves.

And, “I carry my meat over the earth’s lion mouth / & slowly feed my bodies to the dirt” (52). In “Self-Portrait as the Snake,” the snake’s image evokes hidden danger in the garden as well as, simply, the shedding of skins. “Now, / the garden is a skin I wear. Somewhere / in the box of this old house, / my child-skin hangs quietly between the coats, / shed: a parachute or bag full of red dirt & teeth” (59). And, later, “I am older now, but not old. I am looking back / to when I was a girl; now my body’s a flash / of poison on the floor” (60). In “Self-Portrait as the Airplane,” the metaphor would seem to be not an animal, but an object—but it is the speaker pretending to be an airplane in the pool. The airplane is neither animal nor machine exclusively. Later, the speaker’s ears are likened to birds, and bodies: “I am the angel of nothing. / If these ears were birds, I’d like for them to be / flying birds. But the ears are bodies, / they do what they want” (62). Similarly, in “Self-Portrait as the Pirate’s Gold,” the speaker likens her extracted tooth to both animal and object, both to an egg and to a piece of gold loot. The poem ends with “Strange to throw the body in the trash. / I am intimate with the crows and rats” (65).

In the final self-portrait poem, “Self-Portrait as the Snake’s Skin,” the animal metaphors are more varied. Beyond the snakeskin motif introduced earlier in the collection, there are roosters, chickens, the speaker’s “deer,” “a bucket of eels” (66-7). The common framework of bones explain themselves, even when the speaker cannot.

The single poem in the last section, “the book of one small thing,” is “Ars Poetica” (111). True to the theme first established in the epigraph, Girmay’s “Ars Poetica” uses an animal image, that of the snail, to describe why she writes: “May the poems be / the little snail’s trail. / Everywhere I go, / every inch: quiet record / of the foot’s silver prayer” (111).

The intricate use of images within a framing concept made this a rich and satisfying reading experience. Though I am not a poet, I also found this instructive. I can imagine structuring a collection of short stories, or maybe even a novel, around a framework of concepts and images, from the inception of a writing project onward. Or, even if I’m not structuring anything intentionally to start, I hope that whatever I write can come to have a good “framework of bones”—concrete, bodily images that “explain themselves” as the writing proceeds, that announce themselves as both ancient and alive.

Girmay, Aracelis. Kingdom Animalia. BOA Editions, Ltd., 2011.

Lauren Kinney is a writer and musician in Los Angeles. She is a student of fiction and literary translation in the MFA program at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work can be found in Queen Mob’s, Drunk Monkeys, The Turnip Truck(s) and elsewhere. Find her on Twitter @lauren_kinney.

Lauren Kinney is a writer and musician in Los Angeles. She is a student of fiction and literary translation in the MFA program at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work can be found in Queen Mob’s, Drunk Monkeys, The Turnip Truck(s) and elsewhere. Find her on Twitter @lauren_kinney.