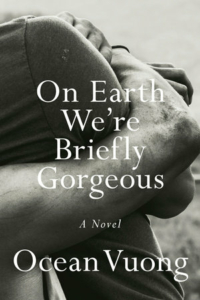

Writers Read: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong is an award-winning author and celebrated poet whose young life and rise to literary acclaim parallels the narrative of his recently published novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous—a hard-won life of survival and self-discovery, full of courage and heart. Vuong’s history is inherently an American story: a farm-boy-turned-soldier from Michigan meets a country girl working as a sex worker during the Vietnam War; they fall in love, a daughter is born; the soldier returns home just before Saigon falls; and a family is torn apart, dismembered in order to survive. Their child is Vuong’s mother—half-American, half-Vietnamese—she is both Rose and Hong. At eighteen, she gives birth to a son who begins his life as Vinh Quoc. Vuong captures the paradoxical arithmetic of his origin in “Notebook Fragments”: “Thus my mother exists. / Thus I exist. Thus no bombs = no family = no me.”

is an award-winning author and celebrated poet whose young life and rise to literary acclaim parallels the narrative of his recently published novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous—a hard-won life of survival and self-discovery, full of courage and heart. Vuong’s history is inherently an American story: a farm-boy-turned-soldier from Michigan meets a country girl working as a sex worker during the Vietnam War; they fall in love, a daughter is born; the soldier returns home just before Saigon falls; and a family is torn apart, dismembered in order to survive. Their child is Vuong’s mother—half-American, half-Vietnamese—she is both Rose and Hong. At eighteen, she gives birth to a son who begins his life as Vinh Quoc. Vuong captures the paradoxical arithmetic of his origin in “Notebook Fragments”: “Thus my mother exists. / Thus I exist. Thus no bombs = no family = no me.”

At two years of age, Vuong emigrated with his mother and grandmother to the United States under Operation Babylift through a refugee camp in the Philippines. The family eventually settled in Hartford, Connecticut, an economically and ethnically-diverse community with a large migrant population simmering with racial and class tensions beneath a tenuous façade of suburbia. School was an amphitheater of bullying and exile for the displaced boy—immigrant, queer, and illiterate until the age of eleven. Vuong’s childhood involved yet another beginning. After divorcing his abusive father, Rose renamed her son. She gifted him a name full of wonder—Ocean—after learning its English meaning: a body of water connecting many countries yet belonging to none. As if his mother had projected an aptronym into the future to unspool and destine itself ahead of his arrival, Ocean claimed its qualities and threaded them into his poetry. His language is oft-described as fluid and his intuitive maneuverings of the English language fish-like—graceful and varied.

Vuong’s debut poetry collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press), published in 2016, captivated readers and critics alike, winning a Whiting Award and the T.S. Eliot Prize, only the second debut collection to receive that prestigious honor. Foreign Policy Magazine named Vuong one of “100 Leading Global Thinkers,” an essential voice in contemporary American political and cultural discourse, rewriting the lines of nationalism with his “reflections on the histories of Vietnam and America, and meditations on identity.” In Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong’s absentee father took front and center stage in mythic proportions. Vuong now turns the page to his personal mythos and our attention to his troubled mother.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Vuong’s luminous first novel, transcends genres and makes no excuses for blending literary forms. The story opens in a hushed refrain: “Let me begin again.” As if we’ve arrived in media res to eavesdrop on a private conversation, we pause and instinctively slowdown as we might when we reach the end of a lyrical poem. The quiet opening is an invitation from an achingly endearing voice to step into intimate space—to come closer and listen: “Dear Ma, I am writing to reach you—even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are.” Vuong’s introspective voice animates itself through his authorial surrogate, Little Dog, a Vietnamese-American writer who is in the act of penning a letter to his illiterate mother—a letter he will never send, one she will never read. Part coming-of-age, part Künstlerroman, part confessional, and part modern myth-making, Vuong’s novel treads in the realm of autofiction, embracing the autobiographical in a story borne from his marginalized circumstances, one he describes as “founded on truth but realized in the imagination.”

Ocean Vuong

That we are in the hands of a master storyteller who writes with a poet’s precision about fractious themes is clear. With a seer’s intuition, he guides us into uncomfortable terrains of migration and displacement, violence and love, trauma and loss, poverty and addiction, the body and identity, queerness and masculinity. Tightly controlled sentences lend his lyrical prose an elegance, reverberating off the page with a musicality that haunts as much as it is haunted. In Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong’s poetry addressed similar themes, orbiting around the underlying question: what does it mean to fashion an American identity when it has to reckon with American violence? Violence as a means to self-knowledge is a motif that repeats in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and unflinchingly commands its own reckoning.

Vuong continues his interrogation of the American identity but adds another dimension in this novel: can words build bridges that transcend the wounds of generational trauma and the legacy of violence? Even if we lend our lived experiences the words necessary for healing, will they be heard by those closest to us?

I am writing because they told me never to start a sentence with because. But I wasn’t trying to make a sentence—I was trying to break free.

I’m breaking us apart again so that I might carry us somewhere else—where, exactly, I’m not sure.

Even after all these years, the contrast between our skin surprises me—the way a blank page does when my hand, gripping a pen, begins to move through its spatial field, trying to act upon its life without marring it. But by writing, I mar it. I change, embellish, and preserve you all at once.

Just as Vuong’s first act of writing was an act of self-preservation, Little Dog turns to English to preserve and protect his family when he realizes the loss of language for them is permanent—“our mother tongue, then is no mother at all—but an orphan… to speak in our mother tongue is to speak only partially in Vietnamese, but entirely in war”—and vows to be their voice—“I’ll never be wordless when you need me to speak for you.” As a creative force capable of building and destroying worlds, re-writing history and universal myths, language itself is another character in this novel, modulating tension between people, between the past and present.

While Little Dog’s voice is central and propels the story forward, it is not singular: “I’m not telling you a story so much as a shipwreck—the pieces floating, finally legible.” Other voices emerge and reverberate through his as a collective echo. Little Dog is a boy from Vietnam who moves to America with his family and settles in Hartford, Connecticut, where his formative years take shape in a household of women traumatized by violence. His grandmother, Lan, is a schizophrenic and his mother, Rose, suffers from PTSD—both war survivors carry their losses on their scar-etched bodies and in their fractured minds. At fourteen, Little Dog is hired as farmhand on a tobacco plant where his notions of masculinity, specifically American masculinity, are challenged and where he confronts his homosexuality. His first relationship and sexual awakening are both tender and tumultuous—he falls in love with the owner’s son, a boy whose self-destruction is fueled by addiction. Little Dog eventually steps into his own life, leaving Hartford for New York, graduating from college, and becoming a writer.

The path there, however, is nonlinear and often illusory, time-bending and fragmented. Using a storytelling convention commonly found in classical East Asian dramatic works called kishōtenketsu—essentially, a plot without conflict—Vuong strives to shift Western narrative arcs typifying our stories. Vuong explains in an interview with Kevin Nguyen: “It insists that a narrative structure can survive and thrive on proximity alone,” and “[that] proximity builds tension.” Vuong thrives on bridging contradictions to draw his characters closer to one another. Love and violence, for example, are Janus twins playing out their eternal drama on the human body. Rose is physically abusive, yet Little Dog reasons that PTSD sufferers are more likely to hit their children, that “perhaps to lay hands on your child is to prepare him for war”—an act of love after all. Little Dog refuses the stereotypical instinct to label mother as monster and therefore villain. Instead, he accepts his mother’s brokenness and re-imagines the fractals whole—as a rehabilitated mother-monster archetype. “To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal,” he affirms, “a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.” Vuong, therefore, creates his own cresting resonances, coaxing us closer and closer towards his intimate voice until his words have penetrated us through vivid imagery, evocative metaphors, lyrical sentences, and repetitive motifs—until his world is as real as ours.

“Dear Ma—Let me begin at the beginning,” Little Dog repeats towards the end of the novel, winding the story back to another kind of beginning. Though understated, Vuong’s tone shifts to a more somber tenor vibrating with measured calmness and unbridled vulnerability before closing the story on a wistfulness that feels surreal.

I never wanted to build a “body of work,” but to preserve these, our bodies, breathing and unaccounted for, inside the work.

In a world myriad as ours, the gaze is a singular act to look at something is to fill your whole life with it, if only briefly.

All this time I told myself we were born from war—but I was wrong, Ma. We were born from beauty.

By rejecting a conflict-centered story with no villains and no victims, Vuong shifts our gaze inward, thereby expanding the possibilities of our literary and cultural narratives. He doesn’t strive for major epiphanies either for his characters or for us. He only beckons that we come closer and look as he shines a light at the spaces between words where darkness cowers and between people where formless wounds still bleed blue, red, and purple. These colors aren’t just for bruises, his voice reassures us—“Look up. See? Do you see? Blue birds. Red birds. Magenta birds. Glittered birds”—the winged and weightless, “flourishing like fruit.”

“And like a word I hold no weight in the world yet still carry my own life,” he writes. “And I throw it ahead of me until what I left behind becomes exactly what I’m running towards—like I’m part of a family.”

Ocean Vuong has gifted us a rare thing of beauty: a quiet, graceful novel filled with wisdom and empathy about the power of language to bridge our disparities and to create new narratives for ourselves—stories to heal and preserve one another as part of one human family.

Vuong, Ocean. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel. Penguin Press, 2019.

Sona Gevorkian is an MFA candidate in creative writing at Antioch University, Los Angeles. She is Lead Editor of the Gabo Prize and the Amuse-Bouche Spotlight and Translation genres for the literary journal, Lunch Ticket. She currently lives in Northern California.