Writers Read: Palm-of-the-Hand Stories by Yasunari Kawabata

The palm-of-the-hand stories anthologized in this collection span decades of Yasunari Kawabata’s life, from 1923-1972, and far pre-date the recent moniker “flash fiction,” though they could be classified now using that label. Most of these stories are realistic, detailing families at home, strangers on the train, and past lovers’ meeting by chance. There are a few moments when the stories take fantastic or surreal turns, but on the whole they tend to have a mythological feel, perhaps because the stories often advance through large spans of time and end with a sentence that encapsulates the final movement of the story. Many of them feel like parables.

The palm-of-the-hand stories anthologized in this collection span decades of Yasunari Kawabata’s life, from 1923-1972, and far pre-date the recent moniker “flash fiction,” though they could be classified now using that label. Most of these stories are realistic, detailing families at home, strangers on the train, and past lovers’ meeting by chance. There are a few moments when the stories take fantastic or surreal turns, but on the whole they tend to have a mythological feel, perhaps because the stories often advance through large spans of time and end with a sentence that encapsulates the final movement of the story. Many of them feel like parables.

As I read, I made notes of which stories I thought worked well, and which didn’t float my aesthetic boat, and why. The stories I favored, tended to fall into two patterns: those that read like parables, and those that were more realistic fiction.

Those that assembled strange and lasting images in obscure parables included “The Maiden’s Prayers” (55-7), which follows villagers who glimpse a gravestone rolling down a hill as they try and fail to locate it, in the process sparking fires and ecstatic ceremony. This story has a tone like a parable but the narrator also seems like an actual person, though nondescript, as in this passage near the end of the story:

The villagers’ hearts were as bright as the sun as they laughed with all their might. Suddenly I stopped laughing and knelt at one of the gravestones illuminated by the fire of the burning grass.

“God, I am pure.”

But the laughter was so loud, I could not hear my own voice in my heart. The villagers laughed in harmony with the maidens until the hill was engulfed in a wave of laughter. (56-7)

Another parable-like story was “The Sparrow’s Matchmaking” (62-4). It opens with this sentence: “Long accustomed to a life of self-indulgent solitude, he began to yearn for the beauty of giving himself to others” (62). The story then proceeds in third-person narration with a chronology of thoughts and actions that feel true to life, revealing deep emotions behind family members’ actions as they toss coins and watch birds, and also conveying archetypal tension between solitude and sacrifices of love. “One Person’s Happiness” (69-71) does something similar in a story with more concrete characters: as the protagonist hears about a boy’s life of hardship, he weighs his decision to help the boy. This conveys his conviction that helping just one person makes life worthwhile. “Morning Nails” (83-4) explores vulnerability in love against a surreal domestic setting. “The Young Lady of Suruga” (85-7) is set on a particular train line, and achieves a strong sense of place.

This is one of the greatest benefits of reading flash fiction: for a writer looking to improve her craft, she can experience at an accelerated pace a diverse range of stories, which can help her gain insight on a wide range of craft considerations, as well as on her own personal literary preferences.

I enjoyed these parables and did not find their tone overly didactic. Though they were like parables, the characters seemed concrete, like real people. If the events conveyed seemed incidental, their effects on the characters in the stories were clear.

There were other stories that stuck with me that were not like parables, and which were more realistic. Some of my favorites were “At the Pawnshop” (121-4), “A Pet Dog’s Safe Birthing” (165-8), “Water” (171-2), and “Tabi” (178-80). These stories presented snapshots of events that are emotionally significant to narrators or protagonists: a desperate and ill man trying to scare up some credit at the pawnshop while another merchant pawns his capital to improve his public image; a married couple assisting in the birth of a litter of puppies, and then sitting down for coffee and a newspaper; a woman in a drought missing her husband and remembering the abundant water in her hometown; a woman who’s lost her sister, recalling the death of her teacher when she was a young teen. The realistic specificity of these stories makes these stories universal in a different way than the dreamy generality of the parables.

What I didn’t like were the stories that felt too episodic. “Toward Winter” (58-61) imbues a routine interaction, playing Go, with a mythical meaning, and then shifts into another story. As a reader I felt ricocheted about until an unsatisfying ending. The way the scenes were juxtaposed didn’t invest me in the story enough, since I didn’t have any other context for the characters therein—it seemed to be more about the author’s musings than about the reader’s experience. I normally consider myself to be very tolerant of cleverness in art, so it was strange for me to experience this aesthetic objection. This is one of the greatest benefits of reading flash fiction: for a writer looking to improve her craft, she can experience at an accelerated pace a diverse range of stories, which can help her gain insight on a wide range of craft considerations, as well as on her own personal literary preferences.

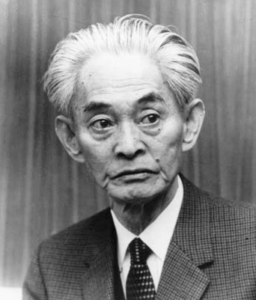

Author of Palm-of-the-Hand stories, Yasunari Kawabata

In leafing through this whole collection after reading it, I realized that some of my favorite stories in this collection involved children: “The Grasshopper and the Bell Cricket” (12-15) and “Yuriko” (88-9), for example. I’ve long been debating whether I want to write about and/or for children and adolescents, and some of the fiction I’m working on right now involves children as characters. Re-reading Kawabata’s stories involving children forced me to reflect on why writing about children appeals to me: they are wise in a different way than adults are. Their problems are less standardized, so writing about a child forces a writer to inhabit their world in its particularity. Children don’t have jobs or spouses, so their preoccupations in play and friendship have more unpredictable symbolic landscapes.

The short length of these stories helped me reflect on this literary interest more efficiently so I could articulate it. When you can hold a story in the palm of your hand, you can examine it from different angles, feel its weight, and you can slip it into your pocket to keep it if it pleases you. Or just as easily toss it over your shoulder.

Kawabata, Yasunari. Palm-of-the-Hand Stories. Trans. by Lane Dunlop and J. Martin Holman. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1988.

Lauren Kinney is a musician and writer in Los Angeles, where she is working on her MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University. You can read her work in Drunk Monkeys, Queen Mob’s Tea House, and The Turnip Truck(s). Find her on Twitter @lauren_kinney, or learn more at her website www.laurenkinney.net.

Lauren Kinney is a musician and writer in Los Angeles, where she is working on her MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University. You can read her work in Drunk Monkeys, Queen Mob’s Tea House, and The Turnip Truck(s). Find her on Twitter @lauren_kinney, or learn more at her website www.laurenkinney.net.