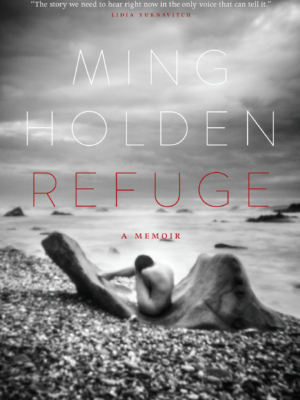

Writers Read: Refuge: A Memoir by Ming Holden

Ming Holden’s essay collection is an experiment. Equal parts essay, memoir, and poetry, with a dash of fiction, Refuge: A Memoir bends genre to immerse readers into the lives of the refugees and political exiles Holden has worked with throughout her life. From Syria to Kenya to China, Holden explores the circular, repetitive trauma that refugees and political exiles experience, even after their journey to “freedom” is over. Holden splices images and stories of her own life throughout her memoir. Through a series of her own heartbreaks, betrayals, and narrowly escaped tragedies, Holden begins to question the moral ambiguity of storytelling. Whose stories are these to tell? She writes: “There is no telling. So I tell it slant”(103).

Ming Holden’s essay collection is an experiment. Equal parts essay, memoir, and poetry, with a dash of fiction, Refuge: A Memoir bends genre to immerse readers into the lives of the refugees and political exiles Holden has worked with throughout her life. From Syria to Kenya to China, Holden explores the circular, repetitive trauma that refugees and political exiles experience, even after their journey to “freedom” is over. Holden splices images and stories of her own life throughout her memoir. Through a series of her own heartbreaks, betrayals, and narrowly escaped tragedies, Holden begins to question the moral ambiguity of storytelling. Whose stories are these to tell? She writes: “There is no telling. So I tell it slant”(103).

Refuge lacks a traditional structure and it works. Holden’s demands that the reader confronts the reality of the violence. Instead of following her experiences in chronological order, the narrative weaves in and out of past and present, timelines blur, traditional structures are lost—there are gaps. “I fundamentally believe,” Holden writes, “there is no thesis statement for rape”(117). That is to say, there is no thesis statement for trauma. With violence, after all, traditional structures crumble. Logic is lost.

One of the collection’s most compelling pieces, “Jaqueline and the Negative Imagination,” centers around The Survival Girls, a theater group in Nairobi, Kenya. Jaqueline, the troupe’s newest member, portrays her own rapist on stage—an act that ripples through the women in the audience and exposes the depth of the community’s wounds. Like all the stories in Holden’s collection, it’s a story about survival. Like all the stories in the collection, there’s no end. For Jacqueline and The Survival Girls the process of trauma is ongoing. Survival continues into tomorrow. “Jaqueline and the Negative Imagination” explores the process of trauma: its effect on the body and the healing capabilities of creativity. It’s also a piece where Holden allows herself a certain amount of theoretical and philosophical exploration. She questions discourse on violence which assuming confine trauma to a period in time: “Violence and its aftermath disrupt the very systems of the mind and body that structure and order experience”(104). Holden suggests that trauma is malleable, fluid, and always changing.

Ming Holden

After reading stories about Jacqueline and the Survival Girls some readers might find themselves asking valid questions: are these stories filtered through the author’s own cultural experience? Does the benefit of writing about these people outweigh the risk of possibly exploiting them? These are questions which followed Holden throughout her journey: “There are vestiges of colonialism all over this work, and certainly they crop up anytime I speak ‘on behalf of’ or even about these women. Especially to a privileged audience”(108). It’s a careful balancing act: writing about pain but making sure not to reduce suffering to shock value. It’s an act which Holden performs well.

In the end, Holden decides the benefit of storytelling is greater than the risk. These are stories that need to be told, and she has the platform to do so. The moral lines are blurred, but she’s not wrong. At a time when the US government is constructing border walls and turning refugees away, stories like the ones in Refuge are powerful and relevant. Holden stripes away the shock value news sound-bites that surround us every day and reminds us that these voices belong to people.

Holden, Ming. Refuge: A Memoir. Tucson: Kore Press. 2018.

Kori Kessler has a degree in literary theory. She just got done traveling Europe and currently attends Antioch University Los Angeles. She is co-associate managing editor of Lunch Ticket and has work published in Tiferet Journal. One of these days she plans on settling down in LA with her dog, Ginsberg.

Kori Kessler has a degree in literary theory. She just got done traveling Europe and currently attends Antioch University Los Angeles. She is co-associate managing editor of Lunch Ticket and has work published in Tiferet Journal. One of these days she plans on settling down in LA with her dog, Ginsberg.