Writers Read: Tell Me How It Ends by Valeria Luiselli

Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions is indeed an essay responding to the absurdity of 40 certain inquiries. Yet, it is much more than that. The “tell me how it ends” refrain quotes a plaintive request from Luiselli’s daughter, who was five years old when Luiselli served as a volunteer translator for an immigration law non-profit in New York. The non-profit took the cases of undocumented immigrant children pro bono, as floods of children escaping gang violence and trafficking in Central and South America arrived in the United States. Luiselli wrote the book as a reaction to this refugee crisis, weaving her stories around the 40 questions required by US Customs and Immigration to be asked of unaccompanied migrant children, many of whom have suffered severe trauma and loss.

Tell Me How It Ends is a case study of this crisis. It is also a case study of education at work—Luiselli’s class in Advanced Spanish Conversation at Hofstra University begins discussing the influx of children at the US-Mexico border, vowing to help the undocumented teenagers now living in the US in constructive and sustainable ways. Tell Me How It Ends is also a tender, personal, and funny story about a rough-around-the-edges Honduran boy, the first child Luiselli met in her volunteer translation work.

One can imagine Luiselli’s early drafts, wrought with dismay and helplessness. The final essay wrings its hands with the same distraught tone, but tinged with hope—Luiselli’s call to action was heard not only by her university students but by non-profits willing to take on children’s cases pro bono. But, as we all know from recent media coverage, the Trump administration has not relented in its commitment to making life for migrant children as difficult as possible. This engrained racism, reflected by ever-more stringent immigration policies, is a clear symptom of the current administration’s lack of understanding of the US’s complicit role in this refugee crisis.

Throughout the book, Luiselli makes neat categorization of an often unclear situation. The essay comprises four subsections: “Border,” “Court,” “Home,” and “Community.” The 40 questions are interspersed in the essay, between Luiselli’s incisive observations and harrowing depictions of the typical child migrant experience aboard La Bestia—literally “The Beast,” a cross-country network of Mexican freight trains that fleeing underage refugees often use to

traverse Mexico more quickly on their way to the US.

These migrant children, usually fleeing gang violence in their home countries, often face graver dangers on their journeys to the border—robberies, rapes and other violent crimes, kidnappings, and extortions. The scenes Luiselli depicts left me in tears as I read the book in late September, just as the current caravan of migrants, most of whom are from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, began gathering to seek asylum in the US.

Luiselli also weaves these children’s stories with her own path to legal citizenship; she waited several long years for her and her family’s green cards while writing the book and volunteer-translating. Luiselli could not legally work in the country, ironic given that her role as a writer enriches the lives and minds of her US-based students. So instead, she volunteered. As the Trump administration continues to ratchet its fear-mongering in the media regarding migrant caravans, I keep thinking of the migrant teenagers Luiselli describes, one in particular who walked the dry, hot plains of New Mexico for hours before two US Border Patrol officers mercifully found and detained him, providing him with life-saving water. I wonder if that would have happened had he traveled in a large group, with the protection of a common cause, the potential presence of relatives, and the ability to forge connections and make friends on the road—a strength in numbers. Migrating people are safer in caravans.

The haunting tale of the first refugee Luiselli met as part of her volunteer translation work winds through the essay. After the teen’s best friend dies in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, shot by members of the now-infamous Barrio 18 gang, the teen fled to the US, aided by his aunt, who hired a coyote—a paid guide who leads unaccompanied minors to the border—to guide him north. Luiselli recounts his response to questions 35 and 36 of the unaccompanied minor intake questionnaire, which ask if the child or his family experienced any problems with the government in their home country, and if so, what happened. The teen shows her the copy of the police report he filed in Honduras against the gang, after the murder of his best friend. The police never did anything, and the teen promised his aunt he would not leave the house until he was able to leave the country for good. He wasn’t able to attend his friend’s funeral. Cue my second crying jag in less than one hundred pages.

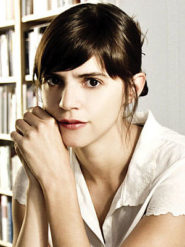

Valeria Luiselli

For this reader, Luiselli’s essay shook the bedrock of my humanitarian core. Drug consumption in the US “is what fundamentally fuels drug trafficking in the continent” (85), Luiselli writes, referring to the drug circuit and its many wars as a “hemispheric war” (86)—“one that begins in the Great Lakes of the United States and ends in the mountains of Celaque in southern Honduras” (86). If the involved governments would acknowledge the hemispheric problem and connections between drug wars, gangs, arms trafficking, drug use, and the massive migration of children, Luiselli writes, maybe authorities would rethink the language surrounding these problems and devise potential solutions.

“No one, or almost no one, from producers to consumers, is willing to accept their role in the great theater of devastation of these children’s lives,” (86) Luiselli writes. “… A ‘war refugee’ is bad news and an uncomfortable truth for governments, because it obliges them to deal with the problem instead of simply ‘removing the illegal aliens’” (87). Finally, some major media outlets, albeit more than a year after the publication of Tell Me How It Ends, have begun examining the US’s economic and drug control policies and pointing at these policies as at least partially responsible for the refugee crisis and the ensuing, asylum-seeking caravans. The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, VICE, and The Guardian all published articles to this tune—addressing the US’s problematic drug control in connection with fleeing refugees—in the past two months.

Going forward, my only concern about the US-Mexico border is our all-encompassing, collective obligation to our planet’s children. Like Luiselli’s daughter, though, I want to know how it ends. Do these children ever make it to relative safety? Do US policies change? What the hell is taking so long? Perhaps if more people read this book—more fully understand the need for the US to acknowledge its responsibility in the migrant crisis—those children at last will be safe.

Luiselli, Valeria. Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions. Minneapolis: Coffee House

Press. 2017.

E.P. Floyd is lead blog editor and weekly content manager for Lunch Ticket, and an MFA candidate in fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her writing is published or forthcoming in Lunch Ticket, Litbreak Magazine, Reservoir, and BusinessWeek. She is at work on a novel and short story collection and lives in rural Wisconsin. Find her online at

E.P. Floyd is lead blog editor and weekly content manager for Lunch Ticket, and an MFA candidate in fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her writing is published or forthcoming in Lunch Ticket, Litbreak Magazine, Reservoir, and BusinessWeek. She is at work on a novel and short story collection and lives in rural Wisconsin. Find her online at