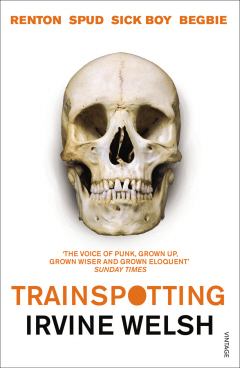

Writers Read: Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh is a work of transgressive fiction that follows the life of heroin user Mark Renton, a.k.a. “Rents,” and his friends known as the Skag Boys. The novel takes place in Scotland with occasional trips to London. Trainspotting is told from several different points of views and includes a revolving cast of outsiders living on the fringe of society. As a work of transgressive fiction, Trainspotting is satirical in its portrayal of characters partaking in illicit ventures and criminal activity in the post-Thatcher United Kingdom.

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh is a work of transgressive fiction that follows the life of heroin user Mark Renton, a.k.a. “Rents,” and his friends known as the Skag Boys. The novel takes place in Scotland with occasional trips to London. Trainspotting is told from several different points of views and includes a revolving cast of outsiders living on the fringe of society. As a work of transgressive fiction, Trainspotting is satirical in its portrayal of characters partaking in illicit ventures and criminal activity in the post-Thatcher United Kingdom.

I was fascinated with how Irvine Welsh differentiated the various perspectives of the transgressive characters through distinctive voices. In Trainspotting, most chapters are written in a Scottish dialect, but there are other indicators of who is narrating each section. Sick Boy, one of the Skag Boys, has an obsession with Sean Connery and imagines speaking with him. “Good old fashioned Scoattish hoshpitality, aye, ye cannae beat it, shays the young Sean Connery” (29). Franco Begbie is violent and psychotic, and the chapters from his his point of view are particularly profane, vulgar, and full of manic energy. Spud says “likesay” frequently and refers to people as “cats.” Mark Renton, for instance, is particularly critical of society. Yet his criticisms are both pointed and ridiculous. At one point he says, “Ah don’t hate the English. They’re just wankers. We are colonized by wankers” (78).

Compared to the other Skag Boys, Renton seems to be the most self-aware. Rents understands the correlation between his behavior and a conservative society. When reflecting on his own contrarian disposition, he says, “Society invents a spurious convoluted logic tae absorb and change people whae’s behavior is outside its mainstream” (187). I read Trainspotting while writing a novel that alternates perspectives between two rebellious characters, a brother and sister who are artists living in New York City. They are non-conformists in the sense that they feel more connected to the city’s artistic and rebellious past than the sanitized reality of the present. When getting inside the various points of view of my own characters, I found that Trainspotting helped me to connect with my own characters’ stylized criticism of society. It also showed me how to differentiate between my characters’ attitudes by creating a unique perspective, bordering on the ridiculous, for each of them.

There are unforgettable scenes that make Trainspotting laugh-out-loud funny and shocking to the core, sometimes at the same time. Though entertaining, it does not glorify the dark side of illicit behavior. One night, Mark meets a girl named Dianne at a club and learns the next morning that she is a teenager. When he meets her parents, he is guilt-tripped into sharing an awkward breakfast with the family. The narrator notes, “Renton thought about last night and wondered chillingly what Dianne had done, and with whom, to gain such sexual experience, such confidence. He felt fifty-five instead of twenty-five, and he was sure that people were looking at him” (150-151). My personal takeaway from reading this shocking material is to strive to be a brave writer. As a writer focusing on characters who find themselves in awkward situations, I tried not be afraid to get my hands dirty. Trainspotting made me realize that perversity in a novel is not necessarily a bad thing as long as it’s not done merely for cheap thrills. Shocking fiction works best when it doesn’t rely on shock value alone to craft scenes.

Irvine Welsh

Trainspotting influenced my writing of provocative characters with nuanced perspectives in outrageous situations. It made me realize that in effective transgressive fiction, characters aren’t rebelling for the sake of it. Instead, there is a greater design to disobedience. The “Choose Life” speech delivered by Rents showed me that characters engaged in rebellion against the demoralizing forces of a conservative society are trying to maintain some sense of higher self, even if that sense of self doesn’t conform to societal norms and standards. Rents says, “Choose life. Choose mortgage payments; choose washing machines; choose cars; choose sitting oan a couch watching mind-numbing and spirit-crushing game shows” (187). In a sense, the characters in Trainspotting are challenging a world that causes members of its society to engage in criminal activity, even if their means of doing so are outrageous, and at times, destructive.

As a writer, I realized that dissident characters can grow into more mature, socially aware selves by taking a stand against elements of society they wish to change. In my novel, the brother and sister who are dealing with the loss of a parent and the subsequent impact on their family, eventually channel their rebellious natures into creative pursuits that help them to transcend grief and loss. Through creativity, non-conformity, and the rejection of social norms, they are able to evolve into their higher selves.

Welsh, Irvine. Trainspotting. 1993. Norton, 1996.

Douglas Menagh is a writer based in New York City. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University. He previously wrote for The New Philadelphia music blog and was recently featured in Annotation Nation.

Douglas Menagh is a writer based in New York City. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University. He previously wrote for The New Philadelphia music blog and was recently featured in Annotation Nation.