On Writing, Fathers and Sons

I began to write after Pipo, my father, passed away. I was a month shy of eight years old. I had learned to read and write only a couple of years before. At first I’d scribble notes on loose pieces of paper like He’s on a business trip, he’ll be back, or He’s still around, I can still smell his clothes. Then there were notebooks, which I hid, afraid that my brother, sister or worst yet, my mother would find them. There was something about writing down my feelings on paper that made them less weighty. As with most things at that age, it felt right but I couldn’t figure the reason, nor did I care.

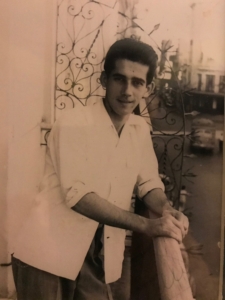

My father, Pipo, as an eighteen year old in Havana circa 1945

I don’t remember much about my father. I do recall that I admired him. I suppose every boy that age looks up to his father. He was always in control, always clean, always nicely dressed in his dark suits and starched white shirts. I felt safe around him. He was our family’s protector, our provider.

One time, he took me with him to play squash with his friends. I was too young for squash, so I just ran around the park while they played. I don’t remember if he was a good athlete, if he was coordinated, if he liked to play, or if it was just an excuse to be with friends. He had one friend who could make his stomach roll like a wave. I remember that day because I laughed with my father, like we were pals. But what I remember most is how much I loved being with him.

I remember asking him to watch me hit one day when he came home for lunch in the summer as I was playing baseball with my friends. He stood there for a minute, leaning on the fence in his suit and tie, he seemed preoccupied, but he smiled as I fouled off a couple of pitches. He checked his watch and went into the house. He might have praised me.

At least that’s what I like to think.

* * *

It was thirty-two years ago today, March 3, 2018. I heard him cry for the first time. And I cried with him. He was my first-born. My son. I had up to that point reached a point of complete and utter apathy. I had lost faith. I’d lost faith in the idea that somehow there was a natural order to life, that things happened in their own time and that it was always the right time.

Me with my son, probably 28 years ago or so

I saw my son’s face through my tears, his swollen eyes shut tight as he rested on his mother’s breasts and it suddenly struck me, I was a father. It felt as though my faith had been restored. How overwhelming that felt! I wondered what type of father I would be. I wondered what being a good father looked like.

And I wrote again.

This time I wrote about how to be a father: I hope I last longer then Pipo. I need to spend more time with them than my father did with me. As I did, I wondered if Pipo had thought about that when I was born. I was his second. Like my daughter would later be to me. She would be born almost two years after my son.

I wrote furiously. I tried desperately to search my memory for my father’s wisdom. To recall any piece of advice he may have imparted on me before he died. I didn’t remember anything other than him telling me not to let any boy touch my ass or my face. (I wonder if he’d feel differently today knowing my brother, who embodies what it is to be a man, is gay). And to never let anyone pick on me. If someone bigger picked on me, I was to find a stick, a rock, anything to even the odds. But never, ever back down. My memory paled over time. For a while my father became a fading black and white photograph on my mother’s dresser, where she would place fresh flowers on the anniversary of his death and of his birthday.

I was on my own.

* * *

I had been raised Catholic. I had been an altar boy and had even considered the priesthood early in life. But those feelings vanished as I grew older and began to consider the absurdity of it all after Pipo died. “There is a reason for everything,” I was often told. “God has a plan,” said others. Then, while I waited to discover the reasons for it, I was uprooted from Cuba, fleeing the Revolution. I landed far away in San Francisco and the reasons became ever more obscure. It would be the second time my imagined life, my plans, and my dreams would once again be dashed. New ones would need to be conjured.

Suburban Train Line at Fontanar Station in Havana, where my friends and I played on the tracks as kids.

I wrote again then. Except this time I wrote letters to all the friends I’d left behind. I wrote to them even though there was no assurance that my letters would ever get to them. But I wrote as much for them as for myself. Again, somehow writing helped me cope. Putting my words down made my memories real and irreversible. Like Egyptian hieroglyphs, my letters became a testament to my past. I wrote to my friends and told them not only what this new place was like: It’s cold, the people aren’t friendly, and I can’t understand them. But I also reminded them, or reminded myself, of all that we’d done together: playing baseball and soccer in the street, running around in the rain, fighting each other, sitting at the train tracks putting our ears to the rail, making bets on how long it’d take the train to arrive, surviving hurricanes, talking about girls. I wrote, I won’t forget.

* * *

In the evenings, Pipo would come home from work and shower. He’d dress again with a light short sleeve shirt and casual slacks. We’d all have dinner as a family. Then my father would leave to go next door for his nightly domino game.

I would sit out front with my mother, sister, and brother talking to the neighbors while we waited for Pipo to come home. I remember begging my father to let me come with him so I could learn to play. He did one time, for a little bit. The game was always four players, sitting around a square table. Dr. Jimenez, a tall brown skinned man with a booming voice whose daughter Isabel was in my class, sat across from Pipo. Mario Sainz, our short, white haired next-door neighbor, whose wife Iluminada couldn’t bear children, sat across from Pedro Plata. I don’t remember much about Pedro Plata other than his pasty white skin. I wouldn’t have known it then, but had he lived in San Francisco, I would have assumed him to be Irish. It was pretty much the same group every night. They smoked cigars and played. I stood behind my father, watching him line up his pieces. “Make sure you don’t reveal my pieces. They can’t know what I have,” he told me. I never did. I wanted him to trust me.

That’s why today, the smell of cigar smoke brings me back to a place when my life was perfect. When that scent comes, I can close my eyes and almost hear the slap of the domino pieces on the table and the chatter of the players, and my father’s voice.

At least that’s what I like to think.

* * *

As my kids grew older, I wrote some more. But this time I wrote stories for them, about funny animals, adventures, and flying elephants. Their innocence and curiosity sparked my imagination. They inspired me. I found that my father hadn’t in fact faded away at all. Did I have the same impact on him that my kids had on me? I wondered if I’d inspired him. I wondered about how my kids would remember me after I was gone.

I’d made my share of mistakes in life, as a husband, as a brother, as a son, as a friend and as a father. Still, I came to understand that my job as a father was to nurture, love and hug my children relentlessly so that they could grow to be better versions of me. Better people. I began to believe that maybe there was in fact a reason for everything. I wondered if growing up without my father, made me strive to be a better one. When I look at my son and daughter, who they are, and what they’ve become, I’d say I’ve done a pretty good job.

At least that’s what I’d like to think.

* * *

Years after my father died and before I married. I sought out my father’s friends who by then were living in Miami. I found Mario Sainz and Dr. Jimenez, his domino partners. I told them how I’d wished I’d gotten to know my father. I asked them to tell me about him, not to hold back because I was his son. I wanted to get to know my father, as a man.

He’d liked women, they said. I knew what they meant. I smiled, not because I condoned it, but because that alone made him frail, more human, and more real. They also told me how he’d been smart and well read, always a man of his word, always a compassionate friend, and most of all always a man true to his family.

* * *

Writing has been my steady companion throughout my life, longer than my father. It has been the bridge between being a son and being a father. Nowadays I write stories like this one. I’m still figuring out life and fatherhood, because that job doesn’t really ever end. I’ve lived nearly twice as long as my father did. But I think about Pipo still, especially when I see my grown son and daughter. I wish they could have met him.

And I think of his warm hand gently tapping my own when I placed it on his shoulder the night I watched him play. As if telling me he liked having me there.

At least, that’s what I like to think.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working through a post MFA semester in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working through a post MFA semester in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.