Saved: Ultrachrome Prints & Poetry

Artist Jody Servon and poet Lorene Delany-Ullman collaborated to produce Saved, an ongoing photographic and poetic exploration of the human experience of life, death, and memory. The project considers how memories of the dead become rooted in everyday objects, and how objects convey those memories to the living.

All images were made between 2008-2013.

Click images below to enlarge.

Gunga’s Lamps

No harp or finial, no shade or socket, no light: the colonial figurines posed on the dresser in the front bedroom. Because Gunga kept old toys—Colonel Custard, the Six Million Dollar Man, and Rock-em Sock-em Robots—her granddaughter, Blair, liked to make the lamps dance—would press the well-dressed courting couples together—the foursome a frolic in her imagination. She was careful with the glazed porcelain, the hand painted gold gilt accents, their delicate boudoir faces—they had been table lamps, but good for girly play. Everything Gunga touched her family wanted to save—but things had to be divided up before the painful yard sale. On a cloudless weekend, Gunga’s objects were sold: big ticket items, the good stuff, now free of sentiment. So, every Christmas, Blair’s brother prepares Cherries-in-the-Snow, an exclusive Gunga recipe—pound cake, cherries, cherry goo, and cool whip.

Mom’s Ring

It’s become a family comedy, of sorts. Everyone knows of Mom’s ring, but no one knows where it came from. Mom conspired with Dad’s family to get them married. All Dad had to do was show up. So he purchased several rings throughout their marriage because Mom always said, “you never bought me an engagement ring.” Dad remembers that this one must have been inexpensive because he and Mom were broke. Their son Allen has learned that it’s a moonstone, or a Feldspar mineral, a stone the Romans once believed to be formed from moonlight. During Mom’s frequent hospital stays, the ring stayed on her bedside table at home. As a boy, Allen liked to sit in his Mom’s lap with her arms around him. He’d play with her cloudy-blue ring, spin it, and move it from finger to finger. Her hands, like Allen’s, were long and skinny—she was six feet tall and very thin. Allen never minded how his hands appeared because they looked just like his Mom’s. He recalls her hands (and that ring) more than her face.

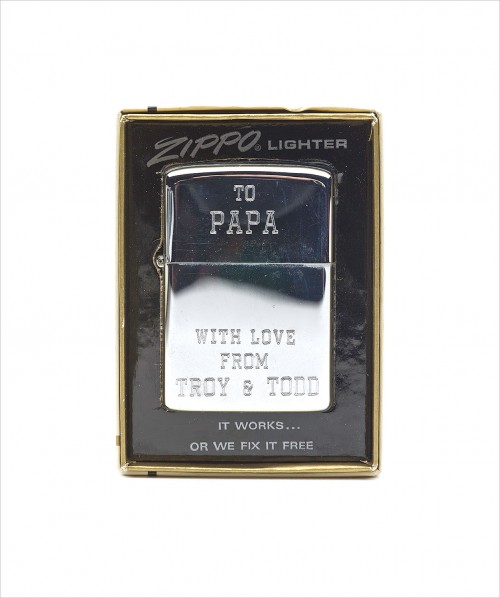

Papa’s Lighter

As steel goes, so goes the nation.

One of the last great American men, Papa donned his red cap, carried a metal lunch box to the steel mills every morning. When steel bars dropped on his feet, he recovered. Then returned to the mill. Nights, he’d sit in his chair, face streaked with hard days worked. Done right. He gardened a little plot, grew cucumbers, cured his famous pickles in the cellar. Sitting on the porch, he’d drink Pabst Blue Ribbon, share apples with his grandson, Troy, while they listened to the Detroit Tigers on the transistor radio. Not a word between them, they’d watch the world go by. The whole family smoked. That inevitable click, vapor sweet—it was too good—Papa kept the lighter in the box, displayed atop his bedroom dresser. His shirt pocket held an old Zippo—one from his drawer full of lighters. Troy swore he’d never use Papa’s lighter. It’s just to keep.

Elaine’s Star

On her first workday at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elaine wore her vintage full-length mink coat. Her lips red, hair bright blonde, she liked the company art kept. After her husband was killed early one morning while riding his bike in Central Park, she sewed stars and other ornaments. Sold them retail. Tim didn’t know any of this; he was drawn to the way Elaine looked that first day. As friends, they’d share a drink at the local bar or go to her Upper East Side apartment and drink too much wine. Those nights he’d ride the subway home to Bay Ridge, asleep on the train. This gold star is one of the only gifts Tim received from Elaine. She didn’t tell her friends—not even Tim—that she married again. Her new husband was a handsome man from Honduras who probably needed a green card. He stabbed and beat her to death when she asked him to leave.

PoPop Sam’s Scraper

It’s not an especially good scraper. Plastic, without a retractable blade, it was a Stanley and PoPop Sam’s favorite. His garage workshop held a trove of tools—with them, his grandson thought, you could fix most anything. He taught kids how to carve bows from local trees; he could nock an arrow, then shoot it with a freshly hewn weapon of his own. On the Gulf of Mexico, he’d take his grandson fishing. For bait, they’d hook live crabs, cast into the currents, and catch sharks. (He knew all the best spots.) PoPop Sam beat a shark to death with a baseball bat—his grandson and fellow adventurer, remembers this fondly. No wonder his bedtime stories were the best you’d ever heard.

Kitty’s Pinecone

Because she was Westward, and swayed by its grandeur, Kitty brought home a pinecone for her friends, Mark and Jen. (The winged seeds are still visible.) Kitty was an artist—she kept dead animals in her freezer so she could draw them. Her hair, long, curly, sometimes frizzy, seemed to want to jump off her head; her hair had a life of its own. Like her smile. In Radford, Virginia, it was big news when Kitty’s teenage daughter, Tara Rose, didn’t come home after work and was found sixteen days later in a ditch, shot four times. Mark remembers the timing—Kitty grew ill with breast cancer—the same spot where Tara Rose had been shot. Mark didn’t know quite what to say or do; he and Jen had moved to Maryland. They keep the pinecone in their living room and love the impossible size of it.

Lorene Delany-Ullman, poet

The prose poems, based on the interviewees’ responses, are meant to evoke the relationships between the objects, the relatives and friends who saved them, and the original owners. We ask the new object-owners to describe their relationship with the deceased loved one, any distinguishing characteristics of that person, a memorable occasion or event shared between them, and what it is that makes the object special. Often the language of the owners is directly incorporated into the poem.

Saved is a collaborative work not only between Jody and me, but also between the new owners and us. As collaborators, the new owners lend their objects to be photographed and tell us the intimate, provocative, and sometimes embarrassing stories about themselves and their departed loved ones that we then preserve along with the images.

Lorene Delany-Ullman’s book of prose poems, Camouflage for the Neighborhood, was the winner of the 2011 Sentence Award, and published by Firewheel Editions (December 2012). She most recently published her poetry and creative nonfiction in Stymie, AGNI 74, Cimarron Review, Zócalo Public Square, Naugatuck River Review, and Chaparral. Her poems have been included in anthologies such as Beyond Forgetting: Poetry and Prose about Alzheimer’s Disease (Kent State University Press, 2009) and Alternatives to Surrender (Plain View Press, 2007). She teaches composition at the University of California, Irvine.

Jody Servon, artist

Saved was conceived after my father and three friends died in a single year. I was affected by how friends and colleagues bearing similar loss openly shared stories of their own deceased loved ones with me. Many felt prompted to tell me about things they held onto after the death of a loved one.

The depth of connection I’d made with the bereaved, led me to borrow and photograph objects that people held onto after the death of a family member or friend. The items are individually photographed on a seamless white background with close attention on the wear apparent of each surface. Most of the images are larger than actual size to reveal intimate details, such as the grime embedded in a plastic scraper or the hairs tangled in the spines of a brush.

Together, Lorene and I composed interview questions for the owners of the objects I’d borrowed to photograph. By email and in person, I interviewed those who had loaned an object to the project, and then forwarded their answers to Lorene.