5 Poems by Feng Na

[translated poetry]

Chinese Fable

When I was small my father’s coworker ran off

coming back with one of those briefcases full of money

close, smutty talk filled our town

about what he’d done to get it

he smiled and disappeared again

Next we heard

he’d been sentenced to death for drug trafficking

a family member claimed the ashes, but the box was stolen in the metro

—It obsesses me, this box

like a fable or something

Other people are like me

they want to know its whereabouts

like standing at the exit

searching for this story’s entrance

Searching for Cranes

Cattle hidden in the prairie shadows

Bayinbuluke I have met a rearer of cranes

his beaked neck

his broken-winged brogue

Cranes dip into the water’s surface

for nine inverted suns

He makes me feel the prairie

misses something of itself

The evening indulges itself in vastness

I wait for cranes to burst from his sleeves

I wish another would drop from the sky

narrow-faced, thin-ankled myself

loved by the rearer of cranes, spurned

and fatuously clinging

Four cornered wildness

She has a hundred and eight ways to hide

to find her, he needs only one:

at night in Bayinbuluke

the cranes he’s touched must all return to roost

Greeting

-After listening to Masi Cong’s “Homesick”

That is no bow

but a tree not yet carved into bow

All my life a river, running low

with fever, has drawn itself

across my body

In Memory of my Uncle He Daoqing

Camellia growing on Xiaowanzi,

forgive a lame man his leg

his timing was poor

he hauled away for half his life

before he found the branch you grew on

The Spring Wind Blows

What drab mercy is this noontime pool

a bird flies to the other bank

felled sugar cane disrupts the mist

By the peach tree is a windswept grave

bees busy themselves long-shoring

this season what is sweet is hard to come by

no birds fly above

to open a vigil keeper’s chest

the earth hums

unknowing of the glories carved into the rocks

the sorrows passed down

as heirlooms

Rifle

I’ve memorized the order: open the breech, load powder and bullets,

close the breech.

Shut my left eye, pretend to be a hunter taking aim.

A bird falls, the trees shudder and descend into deeper quiet.

The metallic cold gives off a living stench.

Since growing up I’ve often smelled it in crowds.

I know the trigger pull and the instant of fire.

I’m glad to live in a country where guns are not for sale.

![]()

中国寓言

小时候,父亲的一位同事停薪留职不知所踪

某天突然出现,腰缠万贯满面春风

关于他的经历,在当地秘密而热闹地流传

他笑而不答,旋即再次消失

再一次听到他的消息

因贩毒在另一个省份被执行死刑

家人领回他的骨灰盒,却在车站被人偷走

——像一个诡异的寓言,它困扰着我

很多人和我一样

一直想知道那个骨灰盒的下落

就像站在出口

想知道这个故事的入口

寻鹤

牛羊藏在草原的阴影中

巴音布鲁克 我遇见一个养鹤的人

他有长喙一般的脖颈

断翅一般的腔调

鹤群掏空落在水面的九个太阳

他让我觉得草原应该另有模样

黄昏轻易纵容了辽阔

我等待着鹤群从他的袍袖中飞起

我祈愿天空落下另一个我

她有狭窄的脸庞 瘦细的脚踝

与养鹤人相爱 厌弃 痴缠

四野茫茫 她有一百零八种躲藏的途径

养鹤人只需一种寻找的方法:

在巴音布鲁克

被他抚摸过的鹤 都必将在夜里归巢

问候

——听马思聪《思乡曲》

那不是谁的琴弓

是谁的手伸向未被制成琴身的树林

一条发着低烧的河流

始终在我身上 慢慢拉

纪念我的伯伯和道清

小湾子山上的茶花啊,

请你原谅一个跛脚的人

他赶不上任何好时辰

他驮完了一生,才走到你的枝桠下面

春风到处流传

正午的水泽 是一处黯淡的慈悲

一只鸟替我飞到了对岸

雾气紧随着甘蔗林里的砍伐声消散

春风吹过桃树下的墓碑

蜜蜂来回搬运着 时令里不可多得的甜蜜

再没有另一只鸟飞过头顶

掀开一个守夜人的心脏

大地嗡嗡作响

不理会石头上刻满的荣华

也不知晓哪一些将传世的悲伤

猎枪

我默记它的顺序:开膛、填进火药铁弹子、上膛

捂着左眼模仿真正的猎人们怎么用一只眼瞄准

一只鸟掉下去,山林抖过之后跌进更深的寂静

铁质的冰冷,冒着生灵附体的腥气

成年后我常常会在人群中嗅到这种气味

我知道扣动扳机的时刻和走火的瞬间

常常庆幸生在一个不允许私人持枪的国度

Translator’s Statement

Here are five poems by Chinese poet, Feng Na. Feng writes about transit, migration, yearning, the great fight for recognition, and the pain of it being denied us. Each poem, I think, offers a window into contemporary China, yet explodes narrow notions of Chinese poets as mere dissidents, or noble savages—as though their poems were good as pamphlets, or expressions of their “authentic, ethnic selves,” but nothing else.

Feng’s poem, “Rifle,” ends with these chilling words: “I’m glad to live in a country where guns are not for sale.” They ought to strike a nerve deep in the American psyche, troubled by school shootings and upsurges in white terrorism, and terrified that America has lost its moral mandate in geopolitics—lost the right to say, in other words, See how barbaric things are in China? Yet the poem eludes this single reading: it is also about sublimation—wanting to harm someone, but transforming this hate into poetry.

“Chinese Fable,” on the other hand, could easily be about the massive economic developments sweeping China in the last several decades, bringing it from one of the poorest and most egalitarian countries, to one of the wealthiest and most unequal. As Chinese markets liberalized some folks were willing to do anything to prosper—thus the man in this fable who is put to death for “drug trafficking.” Yet the speaker of the poem herself cannot monopolize its meaning, which is why she says that it is like a fable. We might say, just as convincingly, that this is a poem about the surplus meaning that escapes even the most airtight analyses, just like the man’s ashes, “stolen at the metro.”

The richness in Feng’s poems complicates our ideas of a China “over there.” Reading her, we realize that we cannot define ourselves against her—we are imbricated with her, just as, halfway across the world, whether she means to or not, her words give us pause.

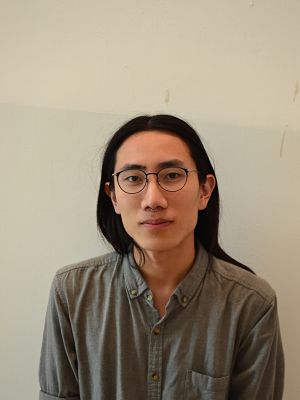

Henry Zhang is a master’s student at Beijing Normal University. His writing and translations have appeared in Drunken Boat, Los Angeles Review of Books, Music and Literature Magazine, and Leap. He is the recipient of the 2017 Henry Luce Translation Fellowship, and his translations have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Henry Zhang is a master’s student at Beijing Normal University. His writing and translations have appeared in Drunken Boat, Los Angeles Review of Books, Music and Literature Magazine, and Leap. He is the recipient of the 2017 Henry Luce Translation Fellowship, and his translations have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Feng Na was born in Lijiang, Yunnan province, China. She is ethnically Bai. Feng works in her alma mater, Sun Yat-sen University, and is a member of the China Writers Association. Her collections include Chosen Night, Numberless Lights, Searching for Cranes, and Tibet in a Season. Her poems have been translated into English and Russian, and have won her numerous awards, including the Lu Xun Literary Award for Guangdong Province, as well as a nomination for the Pushcart Prize. She was the 12th poet-in-residence at Capital Normal University.

Feng Na was born in Lijiang, Yunnan province, China. She is ethnically Bai. Feng works in her alma mater, Sun Yat-sen University, and is a member of the China Writers Association. Her collections include Chosen Night, Numberless Lights, Searching for Cranes, and Tibet in a Season. Her poems have been translated into English and Russian, and have won her numerous awards, including the Lu Xun Literary Award for Guangdong Province, as well as a nomination for the Pushcart Prize. She was the 12th poet-in-residence at Capital Normal University.