Playing House

There was an abandoned house a few miles from where I grew up. It was out on Mt. Mica Mine Road, past the egg farm, past the little cemetery that held just a few toothlike stones, up a big hill and then down the other side. If you did it right, if you let the earth take you, giving yourself and your bike over to gravity, you could plunge down that hill and coast about halfway up the next one. And halfway up the next one was where the abandoned house stood.

There was an abandoned house a few miles from where I grew up. It was out on Mt. Mica Mine Road, past the egg farm, past the little cemetery that held just a few toothlike stones, up a big hill and then down the other side. If you did it right, if you let the earth take you, giving yourself and your bike over to gravity, you could plunge down that hill and coast about halfway up the next one. And halfway up the next one was where the abandoned house stood.

My brother found it. He was always finding things in the woods: quartz crystals, cow skeletons, birds’ nests. A long sandy drive clogged with birch and poplar trees stretched from the road to the house. For some reason, we always walked our bikes down the drive, as if we didn’t want to approach too quickly. As if we needed to listen keenly, muffling our steps as our sneakers squeaked against the sand.

The house had once been painted white, but the paint had faded and chipped so that now the gray of the wood beneath formed the dominant color. A few black shutters clung on, looking like a drag queen’s false eyelashes after a long night.

Here’s the thing: this was and was not a house. It didn’t have to behave—we didn’t have to behave—by the rules of “what it means to be a house.”

We’d prop our bikes against the big trunk of a mostly-dead maple tree and then we’d hop up onto the porch—the front steps had long since disappeared. I can remember being little enough that I had to push myself up onto that porch, like you’d lever yourself out of the deep end of the swimming pool, shimmying on my belly, getting a splinter through my shirt. The front door still stood in its frame, and so we would walk around the porch to where a window had been broken, and we’d step through—one leg, then the other—into what had once been the dining room.

We certainly could have gone through the front door. But it was more fun to go through the window. Here’s the thing: this was and was not a house. It didn’t have to behave—we didn’t have to behave—by the rules of “what it means to be a house.” We could go in through the window.

Inside, wallpaper hung in loose scrolls or had been torn off in rough patches. On a few walls, someone had spray-painted pentagrams in drippy black. The chandelier dangled askew. Across the front hall, through a double door surmounted by a graceful arch, stood the living room. I liked this room best. The floor had rotted away in the middle. But the edges of the wood floor were still intact, forming a rim maybe three feet wide all around. In the center, nothing. A hole. The dirt floor of the basement was visible below. I liked to walk around the outer edge of this room and imagine how it had happened. How the floor had sagged slowly, drooping and drooping, until it just gave way. It looked to me like a volcano. This hole was not one of emptiness but of latent power.

Along one wall of the living room, there was a built-in bookshelf. The volumes had long ago been pulled from the shelves, but many of them still lay strewn across the floor, mostly paperbacks with big, water-swollen pages. They looked like ticks that had enjoyed a nice long feed. I liked to kick them; I liked how I knew books—real books—were solid, but these books—which weren’t quite real books—were squishy.

There were no tales of the house being haunted. My brother never tried to scare me with ghost noises. But, even so, the house terrified me. My brother would climb the stairs up to the second floor; only once did I have the guts to follow him. Actually, I didn’t have the guts, but that day I was more scared to stay downstairs alone than I was to see the upstairs.

I don’t know what scared me more, the emptiness or the not-quite of the emptiness. The fact that some rooms still had curtains in the windows. A few carpets, threadbare and rotten, still covered the bedroom floors. It was enough that it felt like someone not only had lived there, but, in a sense, lived there still. They weren’t quite gone.

Moreover, I just didn’t understand it. Why would you let a house decay? Why wouldn’t you take everything with you when you went?

I loved that house. Well, love is a strong word. You know how when you lose a tooth, you kind of can’t help your tongue from just going right to that gap and feeling around and around, even though it hurts a bit and is kind of gross? That’s what I felt towards that old, abandoned house.

* * *

As a kid, as a little girl, I spent a lot of time “playing house.” I would go to my friends’ houses and we would drape a sheet or blanket over a table and then huddle underneath. As the tomboy of the group, I was always cast as the father, Amanda or Ann would be the mother, our Cabbage Patch Kids or teddy bears would be our children. We played other games, too. We spent sunny days climbing trees and chasing each other in endless games of tag or hide-and-seek. But on rainy days, we played house.

That house was beautiful and horrifying. It had the logic of dreams. It contained those beautiful little things that as a five-year-old I would have desperately wanted in a house.

In the semi-dark, under the sheet-draped table, we would overturn a cardboard box and settle our stuffed offspring around it. Amanda would set plates and teacups on the table. She’d shoo me out and tell me, “You have to come home.” And I would crawl outside of the sheet and sit for a moment on the living room rug, blinking, back out in the boring real-world, the larger house in which we had no interest, which we only wanted to recreate on our own terms. “Okay,” she’d say, “Come home now.” And I would crawl through the sheet and into the dark, orderly place we’d created. This was house.

But this abandoned place, this gaping wounded thing, was also house. House was future. House was hope. But house was also past. House was history. House was memory and decline and decay towards nothing.

No one could play house in this place my brother had found. But someone had. This was a possible outcome of the game. House with hole in the floor. House with squirrel poop in the kitchen. House with pentagram on dining room walls.

I remember walking around and around that thin parapet of living room floor, circling the hole in the middle, trying to be tomboy bold, unafraid of falling in. Unafraid of this place, the mystery of it, its seeming inevitability.

* * *

Years later, I ended up (as one does) working for the Forest Service in Wyoming, in the Shoshone Forest, just outside the eastern gate to Yellowstone National Park. I turned nineteen while I worked that job—my title, wilderness interpreter, implying much more romance than it deserved: I explained the campground regulations to visitors, especially how to store food in grizzly bear country.

That summer, that nineteenth birthday, marked two years of my living as a guy. Two years of being out as transgender. When I had come out to my parents—sitting them down at the kitchen table, telling them I wanted to be Alex, not Alice—they had been upset, confused, sad. Again and again, that day and in the weeks and months that followed, they worried that I had thrown my future away. That I would never be happy, never be loved, never be successful.

I hadn’t been kicked out of anything, not formally, not except for one grandmother who said she didn’t want to see me again. But it felt as if my world had slipped away. It was a strange feeling, a mixture of both elation and fear. After I came out to my parents, I went up to my room and gathered an armful of skirts, dresses, blouses, stuffing them into a garbage bag and setting them aside to donate. I took the jewelry box my aunt had given me and brought it to my mother’s room, returning to her the ring and necklace she had presented me on my sixteenth birthday. It was like handing my future back to her. If I wasn’t going to be this girl, this daughter… What was I going to be?

It was my brother who brought me bits of conversation, who relayed what it was my parents were struggling with. They spoke to him when they couldn’t speak to me. “They’re worried that you won’t fit in. That no one will hire you, that you’ll never get married or whatever.” I worried about this, too. I tried to embrace the queer community, the idea of radical queerness, of turning my back on social expectations: Who needed marriage? Who wanted a conventional job? But some part of me, rooted and formed in that sheet-over-the-table place, wanted, needed that house.

* * *

The Shoshone National Forest contains over 1.75 million acres designated wilderness: rhyolite cliffs, towering buttes, foaming rivers with hot springs in their midst. When I arrived out there, I may as well have been dropped on another planet: the place bore no resemblance to rural New England where I’d grown up. And beyond the landscape, I was preoccupied with trying to be a boy, with trying to convince the dozen other rangers and firefighters at the station that I was just plain old Alex, just another guy. But in the midst of all this, there was one thing I noticed in particular, one thing I couldn’t ignore.

On the highway that led from Wapiti, Wyoming, to Yellowstone, maybe six or eight miles away from the ranger station, stood a large and strange house. It was set back from the road and up a slope so that it was readily visible. No big trees grew to mask it in that high desert.

I noticed it the first time I drove by. It was clear that the house wasn’t really done. The wood was still raw—no shingles, no paint, just bare wood and, in places, only the frame of two-by-fours. At first, I thought the house had some sort of scaffolding on it as it was being finished. But what I thought was scaffolding turned out to be part of the house: a succession of staircases and ladders and platforms and outgrowths that the builder had begun but never finished.

I took to watching the house—it was untouched. No workmen ever swarmed it. No cars were ever in the drive. No lights were ever on. And so, I waited for a full moon and a clear night, and then I went to that house.

I stepped over the chain that dangled across the driveway, with its sign in the middle: no trespassing. I walked right up to the base of the structure. From the bottom, it started off normal enough. A few steps up to a wrap-around porch. Two bow windows. A front door, firmly closed, but with the lock torn out—just a big hole where the bolt had been.

How to describe this house? I walked all over it that night, and it is the strangest place I have ever been. Moonlight makes anything eerie, with its unforgiving shadows. But this place would have been eerie even in full sun.

There were doors in the rooms that opened onto solid walls. There were other doors in the rooms that opened onto thin air. There were staircases that led up from hallways and ended abruptly against a wall or a ceiling. And there were stairways that went up and up, through a roof, and kept going, ending with a step with nothing beyond it.

On the first floor, there were rooms of normal proportions and then, in the middle of the house, one room of precisely half scale. When I walked around the porch, I noticed a tiny window of thick plexiglass and, when I peered through, I could barely make out a cozy little room—the only spot in the house that was furnished—a couch, a fireplace, a little side table, a book. Perfect. But when I went inside, I couldn’t find the room. I walked around and around, before realizing that the room had been built without a door, just a hermetically sealed-off space.

I walked all over that house. It was so strange, so inexplicable, that—in the years since—I have often wondered if I dreamed it all up.

The next day, I asked my boss at the ranger station if he knew anything about the house. “Oh, sure,” he said. Two brothers had bought the land and were going to open a cattle ranch together. They started building the house, but one day during construction, one of the brothers had fallen and died. The other one tried to carry on building on his own, but the grief must have unhinged him because that’s when the house went all crazy.

There are parts of ourselves we can escape, defy, or reinvent. There are parts of ourselves that are unavoidable, hard-wired.

I asked the clerk at the store nearest the house—what’s the story? She told me that a man had come out and bought a bunch of land to open a ranch and was building a big house for him and his new wife. But then his wife left him and he went crazy. Wouldn’t leave the house, even though it wasn’t done. Had his groceries delivered, even, right from this store, and just went on building and building. Loads of lumber would come in and he’d cobble on another room or another staircase. Take potshots with his rifle if any strangers came up his drive. Then just disappeared.

That summer, I heard various tales of what had happened, but the basic contours were the same: man begins building, man suffers loss, man continues building.

That house was beautiful and horrifying. It had the logic of dreams. It contained those beautiful little things that as a five-year-old I would have desperately wanted in a house—a ship’s mast with a crow’s nest growing from the roof!—but that made no sense in the world of actual houses that served actual functions. Trapdoors to secret chambers: such notions had delighted me as a child, but in this house, the secret chambers were stuffy and claustrophobic, prisons as much as safe zones. It was hard to tell whether this was a dream house, spun from fantasy and desire, or something much darker.

Yet, this was house, too.

* * *

That summer, as I lived in an old coal cabin, built by the Work Progress Administration during the depths of the Great Depression, I thought a lot about that house. I thought a lot about the abandoned house of my childhood, the destruction and decay there. I thought even more about the draped sheets over the dining room tables. Odd, that these should seem to be the most real of all. These make-pretend places, where I was the dad, where my friends recognized something in me that I couldn’t see, couldn’t put words to.

I wondered, what place did I have now?

I suppose it is a question that many almost-nineteen-year-olds ponder. At that age, many are confronting the idea that the next house they have will be one they will build themselves. Perhaps not in the sense of build it with hammer and nails, but construct it of their own will, their own selves.

Every time I drove past the crazy house—that’s what I took to calling it—I would slow down and stare, at its spires and ladders and jutting platforms. Who could have dreamed what shape it would take when it was begun? Who had thought, as they set the rugs on the floor, as they hung curtains on the windows of that house in Maine, that someday the living room would collapse in on itself? And who is to say that these fates aren’t beautiful? Who is to say that the original intention is the correct one?

There are parts of ourselves we can escape, defy, or reinvent. There are parts of ourselves that are unavoidable, hard-wired. I had always known I was a boy, and my earliest houses, those sheet-draped tables, had welcomed me home as a make-believe dad. My parents, understandably, set a different table for me. Their daughter, who would one day marry and who would wear necklaces and earrings and dresses. To them, I had abandoned this self, abandoned the idea of house and home that they had constructed for me.

Transgender felt like a crazy word. A wild idea. A renunciation of all that they had intended for me. Queer people went off to the margins, lived at the teetering edges of society, in artists’ colonies and hippie style cooperatives, crazy cobbled-together chaotic places. Abandoned or forsaken by others, we queer folk were meant to gather together in some sort of outcast solace.

House as past, house as future. House as self. I learned that summer in Wyoming, that though I liked living as a guy, I was transgender, and hiding that part of myself did me no good. I could do it, but only at a cost. I came back to the East Coast. I told almost no one about the crazy house I’d seen. I’d taken pictures of the rhyolite cliffs, the snow-capped mountains, the rushing rivers. The house remained only in my mind.

A year or so after that, when my parents were preparing to sell the house I’d grown up in, I took my bike out for a ride on the Mt. Mica Road. Past the egg farm, now closed, and the cemetery, unchanged, up the big hill and down the backside. I kept my hands off the brakes, though the speed seemed unsafe. I let myself coast, slowing mid-way up the next hill. I hopped off. I couldn’t find the driveway. I propped the bike against a tree and walked higher up the hill, then lower. The brush and saplings grew thick and even along the road. I found a stone wall and followed it into the woods, pacing back to where I thought would be even with the house, and walked around. Nothing.

Perhaps it had been torn down. Perhaps I mis-remembered its location. I should have brought my brother with me. But he had already graduated college, had no more summer vacations to spend idly. I picked up my bike and began to pedal back. There were boxes to pack and rugs to roll up and another family waiting to move in.

![]()

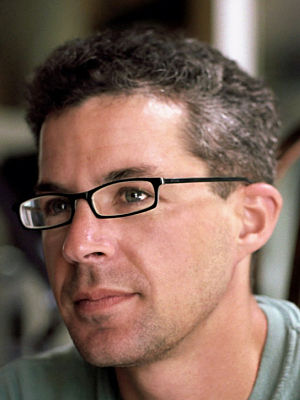

Special Guest Judge, Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich:

“Playing House” drew me in with its unexpected, evocative metaphors and descriptions—its language just slightly off-kilter, as alluring and evocative as the abandoned houses that drew in the narrator and their brother. As I read, I found myself underlining line after line. From its almost haunted opening, to a moving reflection on the houses we find and the homes we make for ourselves, this is an essay that stayed with me.

—Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich is the author of The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir, named one of the best books of the year by Entertainment Weekly, Audible.com, Bustle, Book Riot, The Times of London, and The Guardian. A finalist for a New England Book Award, a Goodreads Choice Award, and a Lambda Literary Award, it will be translated into eight languages. Marzano-Lesnevich’s essays and reviews appear in The New York Times, The Mail on Sunday (UK), Oxford American, and many other publications. They have received fellowships from The National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, and Yaddo, as well as a Rona Jaffe Award. They have taught at Harvard and in the fall will become an assistant professor at Bowdoin College, teaching creative nonfiction.

Alex Myers’s essays have been published in Hobart, Salon, Good Housekeeping, and River Styx. He also writes fiction, and his debut novel, Revolutionary, was published by Simon & Schuster in 2014. Find more at

Alex Myers’s essays have been published in Hobart, Salon, Good Housekeeping, and River Styx. He also writes fiction, and his debut novel, Revolutionary, was published by Simon & Schuster in 2014. Find more at