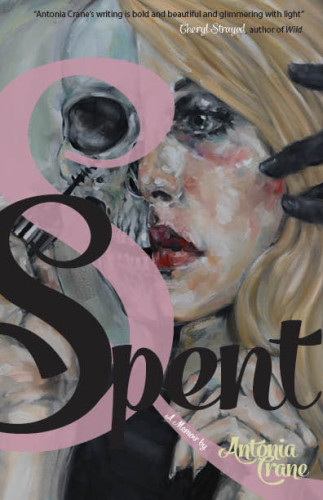

Antonia Crane, Author of Spent

Antonia Crane’s Spent is a memoir for readers who enjoy gritty, surreal narratives and stories that eschew easy conclusions. In Crane’s world, vicious cycles can’t be broken, self-reflection doesn’t lead to happiness, and lessons aren’t always learned. There’s a weariness to Spent that emphasizes the title, an undercurrent of longing for a job that doesn’t come with such high physical and emotional demands. But this isn’t a memoir that goes easy on its author: Crane owns her mistakes as well as her choices, without attempting to explain or apologize for either. If this sounds contradictory—well, Crane owns her contradictions, too.

Spent deals with a variety of events in Crane’s life—her relationship with her mother, her education, her bisexuality, and her sobriety are all woven into the narrative—but the memoir’s main focus is on her series of jobs as a stripper and sex worker in San Francisco, New Orleans, and Los Angeles. The premise’s potential shock value wears off quickly: the day-to-day work is portrayed as routine to the point of dull, with money as the primary reward. During a typical day as a dancer, “time moves like peanut butter;” she describes one customer’s loneliness as an emotion that both “[makes] her sick” and “[feels] like the best thing in the world.” Although Crane claims stripping holds an undeniable, addictive allure for her, it’s easy to believe her when she states that “dancers always want to quit, but we never do. We’re ghosts, dragging our chains from club to club.” At best, Crane depicts dancing as occasionally fun and immensely lucrative; the economics of this work are always at the forefront. At worst, stripping renders her nameless and invisible and trapped.

Crane isn’t always as straightforward about the non-stripping aspects of her life. While there are some standout scenes—the decisions she must make about her mother’s end-of-life care are particularly resonant—some of her choices seem propelled by indistinct motivations and result in few resolutions. These non sequitur aspects of Crane’s writing may frustrate readers who appreciate clear cause-and-effect narratives. Yet although its stream-of-consciousness tendencies sometimes muddy the storyline’s waters, there’s no question that Spent’s style makes a statement. Crane’s still living the life about which she writes; she’s not examining a part of her life that’s already passed, but focusing on experiences that continue to shape her present. If the events of twenty years ago still feel incomplete, it’s because the objects in her rear view mirror are much closer than they first appear.

It’s obvious that Crane has a personal relationship with her work, and not just because, as she says, “without [stripping], I felt ugly, useless, and numb.” During her years in San Francisco, she protests the unfair practices at local dance clubs and helps form the first-ever strippers’ union, a vital need in an industry that exploits women from underprivileged backgrounds. And in some ways, writing a memoir about sex work in unstinting detail is also an act of social justice: Spent isn’t exactly a third-wave feminist cri de coeur, but rather a portrait of a trade in which many of the workers struggle with addiction, abuse, and poverty. It puts a face on at least one of society’s “ghosts.”

Beyond her fight for unionization, Crane doesn’t take much of an outright political stance on the issues facing sex workers; the memoir doesn’t explicitly advocate for legalization, for example, or dwell on the overarching institutional injustices that contribute to an unfair system. But through Spent’s series of anecdotes, Crane makes it clear that for herself and for many of her colleagues, sex work is an unending cycle of survival and punishment. Nothing pays as well or as quickly—a must for women struggling to pay rent, support a family, feed or overcome an addiction, or pay for school without other financial help—but as a result, Crane is harassed, recorded without her consent, and arrested, all for a job that has significantly narrowed her other possible career choices and that will turn its back on her as she ages. “I have no clue how to leave this industry and enter the work force,” Crane says in the book’s final pages. “This is the work force.”

Yet for all the ending’s brutal honesty, Crane also offers a glimmer of hope, although it’s weighed with reality. “This is where I am: I’m still doing this,” she says. “I will climb out, the window is open a crack, but I don’t know when.”

![]()

Antonia Crane is a writer, adjunct professor, and performer based in Los Angeles. She is a graduate of Antioch University Los Angeles’ MFA program. Her work has appeared in a number of publications, including The Rumpus, Slake, PANK, The Los Angeles Review, Salon, and Black Clock. She is the founder and senior editor of The Citron Review. Crane’s memoir, Spent, was published in 2014 by Barnacle Books. Cheryl Strayed praised Crane’s work as “bold and beautiful and glimmering with light,” and Kirkus Reviews called Spent “a raw, searing self-portrait.”

Rachael Warecki interviewed Antonia Crane via email.

RW: In your memoir, Spent, you touch on the fact that words have always been an important part of your life, especially in your childhood. Spent focuses more on words’ importance in your adult life, but I’d love to hear more about how books influenced you while you were growing up. Looking back, were there any books that held a particular resonance for you?

AC: There was not much to do in my small town except climb redwoods, so one of the things my mother and I used to do together was go to the public library. I escaped to my Alice and Wonderland and my Frankenstein with Judy Bloom, V.C. Andrews, and Beverly Cleary, and later I found J.D. Salinger and Jane Austen. I loved stories about heartbreak and families, unrequited love and betrayal.

RW: Your relationship with your mother—an accomplished, fearless, dignified woman as portrayed in your memoir—has clearly been another strong influence in your life, even after her passing. In what ways do you hope your life resembles hers? In what ways are you glad you’ve chosen a somewhat different life path?

AC: I don’t think my life resembles my mother’s at all. My mother went from one long-term marriage to another, kept horses, and belonged to half a dozen women’s organizations. She had kids and was miraculous in the kitchen. However, I am exactly like my mother in other ways—certain facial expressions and gestures are exactly like her, especially in the eyes and mouth. I have followed her lead in the way that she mentored young women and I invest a lot of time helping others, whenever and however possible. I think my path worried my mother some and in other ways, she admired my independence.

RW: You mention that you mentor young women—correct me if I’m wrong, but I heard you volunteer with WriteGirl here in Los Angeles. How long have you been involved with the program? What support do you give young writers as they’re moving toward adulthood? What resources does the program provide that you wish you’d had at that age, and if you could mentor your younger self, what advice would you give her?

AC: I have been a volunteer for WriteGirl’s in-schools program since 2011. I volunteered to teach creative writing to incarcerated teenage girls at Camp Scudder/Camp Scott, where the girls obtained art and English credits towards their GED for participation in our class every Thursday. Our writing exercises approached the personal essay in a lyrical way that offered girls a chance to express themselves and articulate their struggles and obstacles in a meaningful, artistic way. It seemed as if many of the teenage girls had never been told they were smart and creative. When they were acknowledged by reading their work to the class, performing it live, they were elated.

On a pragmatic scale, WriteGirl has a 100% success rate getting girls into four-year universities. We help girls write their college essays in order to springboard them into educational settings, which can change their lives dramatically. In this way, getting involved with WriteGirl and other after-school programs where I’ve worked, such as Woodcraft Rangers, Arc, and Living Histories, embodies social justice.

RW: In Spent, you make several strong economic arguments for why stripping and other types of sex work should be unionized and, in some cases, legalized. In what ways do you see this as a form of social justice? In what ways do you hope to continue this social justice work moving forward?

AC: A group of young women and I unionized a strip club in the ‘90s and it was a powerful time, but it didn’t solve all of our problems by any stretch. Acknowledging strippers (sex workers, dancers) as a work force deserving of basic rights is a good start. Legalizing sex work alone will not keep sex workers safe from domestic violence and exploitation, but it’s a step in a good direction. The goal is toward decriminalization of sex workers in a way that protects some of the most vulnerable members of society from harm and exploitation. It’s a complex issue that deserves attention, time, and change, and every change made won’t be perfect, much like universal health care.

RW: What other steps do you think would make concrete, positive differences in the lives of sex workers?

AC: I think a program that helps women segue into the mainstream would be helpful. Years ago, Sharon Mitchell tried to launch a program for people retiring from the porn industry called “Life After Porn,” but her grant was denied. Sex work is the most difficult job to leave, and it’s difficult to fill in résumé gaps and not be shamed in society for spending a decade (or more) in the adult industry. Going back to school is not enough by itself. I have done that several times. It takes community support to help a person dive back into the mainstream and adjust. It would be helpful to get advice, résumé help, and jobs from folks who are already established in positions to help a sex worker get a steady job.

AC: I think a program that helps women segue into the mainstream would be helpful. Years ago, Sharon Mitchell tried to launch a program for people retiring from the porn industry called “Life After Porn,” but her grant was denied. Sex work is the most difficult job to leave, and it’s difficult to fill in résumé gaps and not be shamed in society for spending a decade (or more) in the adult industry. Going back to school is not enough by itself. I have done that several times. It takes community support to help a person dive back into the mainstream and adjust. It would be helpful to get advice, résumé help, and jobs from folks who are already established in positions to help a sex worker get a steady job.

RW: Your memoir presents a layered and sometimes contradictory portrait of your own role as a sex worker. You mention several times that “every dancer you know wishes she could quit,” but that you personally are drawn back to stripping for the thrill of it, even when presented with other job opportunities. That said, in the scenes depicting your work as a stripper, you often present it as dull, unrewarding work. Can you talk a little more about your relationship with your work, and what aspects of it you find personally rewarding?

I was neither lost nor found. I am just a woman with a couple of cats who needs to write in order to breathe.

AC: All work is rewarding whether I am cleaning houses, waiting tables, or teaching a writing class. If work is a place to be of love and service, which I believe it is, then stripping is the perfect place to demonstrate that kindness. Stripping is physically and emotionally taxing, as well as particularly lucrative. Performing and receiving sexual validation from strangers can be intoxicating. Fast money is a drug. As a job, sex work has been the most difficult to segue out of into the mainstream for the reasons listed above. Other than providing men with a warm body to confide in, there’s a common loneliness that tugs at us when we long to connect to our families, friends, and coworkers in a meaningful way, but fail to do so. I think men search for genuine human connection in a strip club, and that women provide that in a way that can be temporarily satisfying for them [men] and lucrative for us [women]. It’s also a great place to mine for stories.

RW: In your depictions of stripping and sex work, there are many workers and customers who engage in drug use. Has your sobriety ever affected your relationships with clientele or other workers, either positively or negatively (e.g., a client who’s a little too insistent that you drink or get high with him/her, or a fellow sober coworker with whom you form a stronger trust or friendship)?

AC: Drugs are rampant in every workplace. People like to party and tune out. When I worked in a law firm, one of the paralegals was dealing coke throughout the office. People in the medical profession do drugs. As a bartender, obviously it affected my interaction with the customers because I had to cut people off or call them a cab. I have a lot of compassion for anyone struggling with a substance abuse problem/alcohol, and I try to help them get home safely, if possible. Sex workers have a reputation for doing drugs and drinking because it’s expected of us. Personally, I think being sober makes me a better employee in that environment and a more productive person, so I try to be a positive influence.

RW: You mention the difficulty of grad school—of living a life so different from many of your classmates—and yet based on your acknowledgements section, Antioch University Los Angeles clearly provided a strong community for you. How did you learn and grow as a writer during your MFA program years?

AC: The decision to do sex work while in grad school was my own solution to creating as much time to write as possible. Antioch provided an incredibly rich community of mentors and peers, many of whom I still have close relationships with. My graduating cohort, The Citrons, has been checking in every Sunday since 2009. When I attended Antioch, it was like I could finally give myself permission to write and to have access to writers I admired, like Rob Roberge, Emily Rapp, Cheryl Strayed, Leonard Chang, and Steve Almond.

RW: At the end of Spent, you acknowledge that you have not yet achieved your ideal vision of happiness—no partner, no agent, no publishing deal. Obviously, with the publication of Spent, some of that has changed. How have you come closer to achieving your personal and professional goals? What’s next for you?

AC: Every day, I work towards my goals and aspirations regardless of my circumstances. The end of Spent was more of a comment that sex work itself can be its own happy ending. I didn’t need to be rehabilitated or killed or saved, imprisoned or forgiven; I wasn’t married off or carried off on a magic carpet ride. I was neither lost nor found. I am just a woman with a couple of cats who needs to write in order to breathe. So, I’m going to keep doing that and see what happens next.