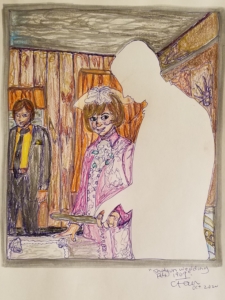

Bob’s Bass Turd

Shot Gun Wedding, Rome City, Indiana

In the recovery room, I was groggy but anxious for Dr. Hurley to come in and tell me what he found or didn’t find in this most recent invasive and humiliating exam. I had lost count of the myriad barium studies, endoscopies, colonoscopies, and the exotic and costly drugs that came onto the market for this inscrutable disease called “irritable bowel syndrome.” “Syndrome,” I learned, is a weasel word that was invented to placate insurance companies demanding a diagnosis howsoever useless. It’s a clinical confession that while there are a bunch of symptoms, there is no meaningful explanation for them and no effective treatment for the underlying, unidentified cause. It’s the medical equivalent of throwing turds on the wall to see which ones stick. My chest clenched as I heard him speaking around the corner in not-exactly hushed tones. When he finally pulled back the curtain and offered a milquetoast greeting, I concluded from his rumpling forehead that he had nothing useful to offer this time either.

“Lucy, we’ve done every possible test. Repeatedly. Frankly, in my view, we’re treating the wrong end of your problem. The symptoms are in your gut. But the problem, in my opinion, is in your brain. You present with an extensive, well-documented experience of several kinds of childhood trauma. We are increasingly learning that what you’re experiencing is extremely common among adults with your history. I’m sorry. I really am, but I can’t help you. You need to see a psychiatrist, perhaps a behavioralist. I strongly recommend that you find someone who specializes in PTSD. I can keep throwing drugs at your gut. I can make you have bowel movements. I can control your acid reflux. I can mitigate the nausea. But fixing this problem requires the skill of someone who can fix your brain and you will probably need meds for that too.”

“So, Dr. Hurley, do you have any suggestions or referrals for such a shrink? Preferably, a doc who will accept my insurance…” Dr. Hurley curtly interrupted. No doubt he had rehearsed this many times before with other patients like me. “No. No one. Given my burgeoning patient base with these problems, I should.” I glowered at him with my best “What-the-Actual-Fuck” face and left. I long ago concluded that doctors suck. My dogs have better healthcare and better coordination across their varied providers. Physicians are basically lesser talented veterinarians who get away with specializing in one organ system of one species. It’s absurd how little they get away with knowing about entire human bodies.

Driving home, I was steeping in rage. Partly, I felt helpless in the assigned task of finding someone to fix my brain. But also because there is a cast of characters—many of whom are dead now—whose grotesque cruelties apparently haunt my body like somatic poltergeists. How the fuck am I supposed to exorcise these assholes lurking about my guts and head?

When I got home, I crawled into bed straightaway. My dogs followed suit. My agile girls leapt upon the bed and packed around me like insulation from a world against which I have long waged war. My old girl, Saphy, curled up on her dog bed at the foot of mine. This was the singular place where I felt safe from the present and my past and these wretched shits lurking around my body as unwanted now as they were then. And in that space between being awake and asleep, Bob floated into my mind. Ordinarily, I would stop my brain right then and there. But this time, I let Bob’s bullshit wash over me.

* * *

Bob was my first non-memory. I knew his absence without ever knowing his presence. In the negative space he occupied, my life slowly piled up, one angry and confused ossifying sediment at a time until, finally, I grew into the image of his nonexistence. At times, his non-memory lingered in the background like quietly spewing elevator music. But at times, like now, it roared like an eardrum-shattering cacophony.

The first time I acutely felt his nonmemory occurred at John’s General Electric family picnic sometime after he became a journeyman. John was my mother’s husband and he worked on GE’s factory floor, which required steel-toed shoes. He preferred dark brown wing tips, which disguised the industrial nature of his enormous footwear. At size thirteen, his feet in those shoes reminded me of the sleek speedboats I sometimes saw on Sylvan Lake. In the oddly verdant park in Fort Wayne, the employees’ kids raced in burlap potato sacks, struggled to push their siblings along in wheelbarrow races, and raucously tossed bean bags into their cornhole targets. The adults played croquet or stood around drinking. Most gulped Pabst Blue Ribbon from steel cans with pull tabs, which, despite the well-known dangers, they wrenched off and deposited into their cans before drinking. How many times had I wished that John would choke on one of those tabs? He never did.

Things became awkward when John’s colleagues expected an introduction to his motley miserable ensemble. After exchanging the manly gestures of reciprocal head nods and random gesturing with their cans of beer in the air, John would pick up Joey, my little brother, and run his calloused hands through his impossibly blond hair. When his co-worker lingered awkwardly while looking in the direction of my mom and me, I instinctively clung to mom’s legs hoping she’d protect me from what would come next. I felt my stomach seize up with cramps. I imagined becoming a wizened dandelion whose feathery seeds floated away on the breeze unnoticed before I had to hear it. Again. John would stumble onward with a bit of a stutter “Um…. Well… This is my wife Sandy. That’s her kid.” Reduced to a “that,” I didn’t even merit a female pronoun. Breaking into the conversation, Mom offered cheerfully, “Her name is Lucy.”

When the young, miserable couple fought—and that was often—John frequently hollered about a certain “Bob’s bass turd” and accused her of marrying him for a “meal ticket to pay for Bob’s bass turd.”

I wasn’t too sure about what a “bass turd” was. Grandpa Austin liked to fish for bass and he’d often take me with him. In my little mind, I presumed it had something to do with those bass that Grandpa liked to catch with me by his side and their small fish turds. I comforted myself with the knowledge that my family deployed toilet humor lovingly. John had nicknamed Joey “the pot licker” because he lapped up the cool condensation from the toilet bowl.

I furiously tried to stitch together the words, the sounds, the feelings and unfeelings from these various interactions with these people and the world they—and I—inhabited. I knew that I had a mother named Sandy, a brother named Joey, and that Joey and I had the same mom. We also shared Grandma and Grandpa Austin, who were our mom’s parents. Mom also had a sister and two brothers who were our aunt and uncles.

But John’s family was murkier, harder to parse. There was no love for me among his clan. No one kissed me or hugged me goodbye. Rarely did anyone ask how I was or how school was going. They always and only cared about Joey.

And, of course, there was John and the unmemory of that unseen Bob who had a mysterious bass turd, whom I eventually discerned was me.

I was pretty confident that I didn’t have a father. There was no one I called “dad” and there was no one who called me “my daughter” or even “my kid.” Whereas Joey called John “dad,” I addressed him as “John.” Frankly, I avoided going near him because he was a mean son-of-bitch who usually didn’t hide his disdain for me. As a grown woman, I learned that my mere existence reminded him that another man knew my mother’s body before he had and that he knew this “Bob” from childhood and detested him for more reasons than I would ever understand.

* * *

He couldn’t cut straight. Hell, he couldn’t even fold the damned paper properly. He even managed to get glue all over his glasses, which resembled boogers streaking across both lenses. While I was annoyed with him, I was even more jealous. I wanted a dad too.

My last first-grade assignment pulled everything into horrendous clarity. At the fag-end of the school year, Father’s Day loomed. This holiday was as enigmatic to me as Ramazan or Diwali. As the heat soared in our fan-less, un-airconditioned classroom at Abbot Kinney Elementary School on the South side of Fort Wayne, our teacher giddily heralded an exciting end-of-year project: “You are going to make a Father’s Day Card!”

My heart sunk. I felt the pang of diarrhea sweep over me as often happened in moments of such terror.

I approached Mrs. Bentley to go the bathroom. I made it just in time. As my tiny body emptied itself into the toilet like one of those frightened sea cucumbers that I learned about from an afterschool television show, I deliberated upon my dilemma. As a diligent student who took all tasks big and small with great earnestness, what would I do? What could I do?

I returned to the classroom and stood by Ms. Bentley’s desk and waited for her to ask what I needed. With tears of shame and indignity pooling in my eyes and my stomach loudly hollering, I sheepishly whispered “Mrs. Bentley, I don’t have a father. What do I do?”

In 1974, Mrs. Bentley could probably be forgiven for her presumptuousness. And, in her defense, she did seem a bit flummoxed as if this problem had not previously arisen. She queried somewhat plaintively, “Well, Lucy, can’t you make a nice card for your mother’s husband, John? Isn’t he your stepfather?”

This confused me even more. “Mrs. Bentley, what are stepfathers and what do they do?”

Growing exasperated with this unanticipated challenge, Mrs. Bentley offered several bromidic suggestions. “Well, Lucy, they love you. They hold you when you’re sad. They take you to the doctor when you’re sick. They help your mom raise you. So, they are basically a dad.” She said all of this with smug confidence as if she had resolved this impasse. “Um, Mrs. Bentley… Well, John isn’t like that. He hits me. Yanks me by my hair. Also, he calls me names and kicks me with his big shoes. Is John still my stepfather?”

Mrs. Bentley gave me a faint and unpersuasive smile. She said, with gentle encouragement, “Just do your best, Lucy. You always do.”

On those words, I set about the assignment. I selected a brown piece of construction paper and a picture from a magazine of what appeared to be a loving and dashingly handsome man holding who was likely his own toe-headed daughter on his lap. They both smiled with perfect teeth and with matching sky-blue eyes. They were impeccably dressed. They looked absurdly happy as the photographer snapped them mid-laugh. I took a modest collection of gold stick-on stars, some gold glitter, and a small bottle of glue.

Back at my desk, I wondered what a picture of John and me would look like. I was chubby, with wild mouse-brown hair, bespectacled, and wore boys’ hand-me-down clothes and shoes. I stood around like Winnie the Pooh with my potbelly protruding. On special occasions like Easter, mom sewed me dresses that were inspired by Little House on The Prairie. John was tall and lanky. His spindling arms and legs seemed oversized. He reminded me of an emaciated gorilla. His glasses never stayed on his flat nose and his butt crack frequently peaked out of his pants that struggled to catch hold of his narrow, bony hips. I couldn’t imagine plopping my chubby self on his rangy lap like the father and daughter in that picture.

Pushing that impossible image out of my mind, I tried to focus on the task at hand. I folded the paper horizontally and made a near-perfect crease. I wielded my scissors to cut out the man and girl precisely. I applied just the right amount of glue that would hold the enviable father-daughter duo in place without unsightly glue squishing out onto the paper and spoiling the front of the card. I thoughtfully placed a small number of stars over their heads as a sure sign that someone in heaven thought highly of these two because they were impossibly beautiful, happy, and loved.

Inside, I drew a thin heart in glue and deftly, yet abstemiously, cast the glitter upon the glue. I waited patiently for my glittery heart to dry. Then, I removed my Crayola sixty-four count pack from my desk and pondered the colors that went best with the brown card and gold stars and faint gold heart. I withdrew the rarely used gold crayon and, as best as I could in my still largely unlettered hand, wrote:

Dear John

Happy Stepfather’s Day.

Bob’s Bass Turd,

Lucy

Mrs. Bentley made her usual rounds to check on our progress. She congratulated me on the care with which I folded and decorated the front of the card. Encouraged, I enthusiastically and with an open face, proffered her the card to examine. My innards ached for her approval.

Mrs. Bentley was nonplussed. She nodded her head noncommittally and moved onto Ronald Oliver’s desk. Ronald could never do anything right. He had a dad and had no reasonable excuse to be making such a hash over there. He spilled glitter all over the place and gave himself a dusting of glitter on his gray polyester pants. He couldn’t cut straight. Hell, he couldn’t even fold the damned paper properly. He even managed to get glue all over his glasses, which resembled boogers streaking across both lenses. While I was annoyed with him, I was even more jealous. I wanted a dad too.

At the end of class, I began trudging home with that card in my bookbag with the plan that I would toss it in a dumpster. I took the longest possible route home. I circled superfluous blocks and I stopped to greet the various dogs behind their fences. I dallied about looking for flowers that were in bloom to smell. Eventually, I turned down the alley behind our backyard with the dumpster in sight. Suddenly, mom bolted out of nowhere like a banshee, in a crazed fit of rage. She hurtled towards me with wrath in her amber eyes and grabbed me before I could reach the gate. I felt her nails digging into the flesh of my arm. My arms were covered in scabbed-over or scarred half-moons from past episodes.

“Goddamnit, you little fucker! Why can’t you just be normal? Why do you always have to embarrass me? Go get me a switch. Now,” she thundered.

I dreaded those moments when she became a monster.

While I wasn’t sure what I had done to deserve this, I suspected it had something to do with the card and I knew not to give her lip or even ask why I was in such trouble in moments like this. I also appreciated the peculiar predicament of obtaining a switch for her. If it was too small, she’d furiously whip me with whatever she found lying around, be it a hairbrush, a shoe, some random pipe, or sometimes she’d just wail on me with her fists until she was exhausted. If I picked an unnecessarily big branch, then I was inviting excessive punishment when a smaller one would have sufficed. I brought her what I assessed to be the Goldilocks stick and she did her needful.

After she had her catharsis and let go of my bleeding arm, I ran straight to my room and clambered into the upper bunk in the bed I shared with Joey, who slept below. I curled up with my blue baby doll and whimpered. I asked an increasingly useless god why I was alive given that no one wanted me. I prayed that I’d fall asleep and never wake up. I didn’t come down for dinner and no one came to get me.

At some point in the night, mom softened and maybe even felt remorse for thrashing her hapless, wretched daughter who understood so little of their shared fuckery. She approached the bunk. Her eyes softened and she stroked my tear-soaked, tangled hair. I thought perhaps she too had been crying. She explained that Mrs. Bentley called to discuss her concerns and that this was very, very embarrassing for her. Then, she too began to sob loudly. “Lucy, I’m doing my best. I don’t know what else to do. I can’t make John love you. But you had no goddamned right to tell Mrs. Bentley anything about our home. You have no respect for me or the sacrifices I make for you.”

Even as a young girl, I knew that she was trying to make me feel sorry for her. And it worked. I felt bad that my existence imposed this hardship on her. If only I had died like baby Johnny, she’d be happier. I tried to look at her. But I couldn’t see her clearly. My eyes were swollen from crying and my glasses were smeared from tears and sweat and my mother’s fingerprints from the whooping as she tried to get a firmer grasp on me. I pleaded with her to explain, “Why am I Bob’s bass turd? What is a bass turd and what did I do to be that? And who is Bob anyway?” My bones thirsted for these truths.

In an empty gesture, she patted my head and warily uttered in a hushed voice as she walked out of the room, “I don’t know, Lucy. I just don’t know.”

* * *

Lying in bed, I drew Daisy pup to my chest and held her tightly as my stomach contracted and its contents burst up like a volcano in the back of my throat. I waited for it to pass and drifted back to an uneasy sleep, fearing that I would never be able drive these devils from my entrails.

C. Christine Fair is a professor in Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program within the School of Foreign Service. She studies political and military events of South Asia and travels extensively throughout Asia and the Middle East. Her books include In Their Own Words: Understanding the Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (OUP 2019); Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (OUP, 2014); and Cuisines of the Axis of Evil and Other Irritating States (Globe Pequot, 2008). Her forthcoming book is Lines of Control: Lashkar-e-Tayyaba’s Militant Piety, with Saifina Ustad (Oxford University Press, 2020). She has published creative pieces in The Bark, Dime Show Review, Clementine Unbound, Awakenings, Fifty Word Stories, The Drabble, Sandy River Review, Sonder Midwest, Black Horse Review, The Furious Gazelle, Hyptertext Magazine, Barzakh Magazine, and Bluntly Magazine, among others. Her visual poetry has appeared in Awakenings, pulpMAG, and several forthcoming pieces in Abstract: Contemporary Expressions, The Indianapolis Review, Typehouse Literary Magazine, and PCC Inscape Magazine. She causes trouble in multiple languages.