Hieroglyphics

If we are to begin this story, it  begins with melancholy and nothing more, the interminable lapse of what we forgot on those islands.

begins with melancholy and nothing more, the interminable lapse of what we forgot on those islands.

We would joke about you riding the carabao as a boy in the province—a loincloth chafing against the rough hide, still a savage wading through rice paddies—a boy on a beast, on an island in a field. It would not be until I am in graduate school that I would find out that the year the family left the islands coincided with the martial law of Marcos, a diaspora triggered by American appeasement in the Philippines.

Dad, I know if you were to read on, you’d know that none of this was real, knowing that the truth is eventually erased by our present, and so I narrate the irreconcilable.

I start with an afternoon in second grade while I wait to be picked up in the parking lot. The stream of cars and children jumping in like a monochromatic carousel. One by one, grade by grade. I hear the Oldsmobile, see the bumper sticker reading my kid beat up your honor student, from beyond the school’s wall, beyond this procession, because you always wanted to make an appearance. The muffled riffs of Van Halen pulsating through the heaving, rumbling engine.

It dies, and then here you come.

The aviators and fitted Guns & Roses T-shirt. The relentlessly long, black hair absorbing the autumn sun. I run to you, and the playground attendant is yelling at me to stop running because I’m supposed to wait to be checked out, but I run anyway and wrap my arms around you because you’re my dad.

Here you are, my dad. The man who, in the seventies, was a dark, wild boy from the Philippines, who shed the mottled skin of the demure immigrant and transmuted this wildness into the indignance of the heavy metal scene, who hacked off the language of his mother’s tongue and grew America in its place.

Dad, I know if you were to read on, you’d know that none of this was real, knowing that the truth is eventually erased by our present, and so I narrate the irreconcilable.

Here was the man, the boy, who understood that survival is not taking beatings in a new land, but instead, that survival is simply a matter of aesthetics. That to stay alive, you are at once the floodlight and the darkness that surrounds it.

On that day you picked me up from school, I showed off my new book from the Scholastic book fair, a choose-your-own-adventure about a sentient computer on the moon. I told you that I had already cheated and dog-eared the bad endings. Pride in being able to cheat my own death.

You smiled and praised me for a precocious cunning, but, as you flipped through the pages and found the true finale—because this was a book for second graders, after all—you handed it back and said, You know, you’ll get to the end eventually.

But unfortunately, that day, I learned that conversations aren’t meant to be held in the middle of a driveway, because to the observer, our presence, a presence without words, is simply an inconvenience.

Someone behind us is yelling as if the truck itself was fueled by screams: a woman’s voice battering against the glass, muffling the words but not her rage. I am shoving the book back into my backpack as my dad pulls me to the side of the driveway. She pulls up beside us to slow down and roll down her window, her pale face now hollowed out by her screaming. Get out of the fucking way. Fucking typical Filipinos. I am staring at her as she says this, my backpack ajar with the book halfway out, and she looks at me, then at you, and then back at me.

What does it mean, Dad, to be marked as typical?

That word: the thing meant to brand us—our typical hospitality, our typical accents, our typical noses—is also the thing to sweep us back into ourselves, to be just like the rest of us.

To think that my only self requires to be seen and unseen. The way some images only appear if you slowly pull your face away from the page.

Like claws unsheathed, your fist swipes the glass before she is able to drive away. Fuck you, white bitch, you scream, but it is only met with trailing exhaust and the smell of warm asphalt as the target slips away from you. Typical, you say, as if it were a sentencing handed down.

We pick up dinner that night at the Filipino market on Colorado Blvd., each large Styrofoam container hoping to be enough to last us until the end of the week. When the woman behind the counter calls out our number, you point out the ulam on the other side of the glass. Although you can’t avoid calling out each dish in Tagalog, every word you speak is with reinforced English.

Typical, you tell mom over dinner, as if you were trying to scrape it from your teeth. You run your hand through your hair and pull, your teeth gnashing as you apply pressure.

It was the first time I witness what it means to be exposed in America. It is the first time the light breaks against the surface and reveals the color that remains unclaimed.

Typical, you repeat to yourself that night, long after mom and I have gone to bed. You are alone with the language you are learning as a new father, alone with a word that has already splintered beneath your skin. Alone with a row of empty Budweisers sticking up through the carpet, the light from the TV spills amber shadows that only look like stains. Fuck that.

* * *

Baseball is the only major sport in America that does not progress through time. It is suspended throughout its nine innings, its progress only determined by contact. The ball in the glove. The glove sweeping the tag into the runner. Timing exists only between pitcher and batter, its purpose only to disorient the momentum of the swing. The strike is the only rule that moves the game forward without contact.

Anak, the ghost of you tells me as I think of this, the same way you told me in the batting cages in Glendale, or during my games where I’d walk back to the dugout with my head down, it’s easy. Just keep your eye on the ball.

In 2015, the MLB announced plans for the twenty-second pitch clock, a response to the growing discontent of the length of the games. On average, a pitcher assessing any runners on base, then coordinating pitch and location with his catcher, hardly ever reaches the twenty-second marker. But the America I live in can no longer synchronize its pace.

I think about this now, how the human need for time, the endless dissection of our existence, is imprinted on a thing that does not need it.

I think about how at the LA County Hospital on the night you died, I had walked out of the room to announce your heart had stopped. It was 10:07 p.m. The nurse looked at the monitor, then confused, said, No, he’s still alive. Because our life doesn’t end with the heart but with the mind.

When I walked back into the room, she followed shortly after and confirmed that you were no longer there. It was 10:08 p.m. A timer I didn’t need.

* * *

June 19, 1977. The marine layer has cleared way for the bright afternoon at Dodger Stadium as the Dodgers close their series against the Cubs. Before the game, the players play catch with their kids, mostly toddlers, picking up wild throws lapping slowly toward them. The cameras pan around the smiles as Vin Scully narrates, for those moments, the stories of fathers and sons. The crowd is brought to a tranquil scene, a scene replicated behind their own picket fences, in their own pristinely manicured parks, reminding them of American wholesomeness as they spend their Father’s Day afternoon in the Chavez Ravine.

In the first inning, Dodgers right fielder Reggie Smith is hit by a pitch. He charges the mound and swings at Rick Reuschel. Afterwards, Smith swears that he connected with Reuschel’s jaw, but Reuschel refutes it. The crowd now filled with latent desire—that sudden, subtle anticipation for blood.

Father’s Day in America.

At the bottom of the Ravine and to the west, further down on Beverly and Alvarado, you are in your room in the single story house where I would also form my first memories. You are only seventeen. That night, there’s a party you’re going to with your sister and her boyfriend.

But right now, you are alone in the house because the rest of the family—your mom, your siblings—are visiting your dad at the cemetery. Instead, you stay holed in the room, Zeppelin beating against the walls and tremoring against the window, only coming out to grab a coke from the fridge, cigarette burning at your side. Robert Plant croons “The Song Remains the Same,” the first track to Houses of the Holy. The album cover, a cluster of children climbing across alien rock formations; its eeriness, its cold distance appealing to your nascent understanding of the states.

You told me, only once, how your dad died of lung cancer when you were sixteen. How Benjamin Sr., the stoic disciplinarian, writhed and withered in his final moments. He looked at me, you said, but he didn’t remember who I was. I called out for him. “Papa. Papa. It’s me. Benjamin.” But he just yelled. So intensely that he passed away with his wrists tied to the bed. In your grief or rage—because now I understand that in those moments they are indistinguishable—you broke your hand throwing wild fists into the brick walls outside.

The family returns and now all that’s left of the day is the party. Grandma is sitting on the couch, an open Bible between you and her as she only glances at you from the other side of the living room. Mag ingat kayo, she tells you. And like so many times you’ll experience, the rift between the two of you widens.

Your sister forgot to tell you that the party is actually her ex’s birthday, and that she’s also invited her boyfriend and his brothers, the Mexicans from East LA already stumbling into the backyard, boisterous. The rest of the crowd keeps their distance, staring indiscreetly as the brothers throw back beers in the corner. You hate the way Filipinos stare, always reminding me as I grew up, and tonight, seeing this, you decide to drink with the outsiders, now under the ire of a derisive gaze.

Within the next couple of hours, you and the brothers are pilfering the ice chests for more beers, your corner now littered with cans that look like mottled skins. Ernie, the birthday boy, comes up to you, recognizing you as the only Filipino in the group. Hoy, pare. Tama na yan, he says, trying to close the cooler with your hand inside. Get your hand off the fucking lid, you say, pausing to look him in the eyes, pare.

Your sister’s boyfriend—who she will eventually marry when she becomes eighteen—opens the lid of the rice cooker on the table nearby, and calls out to Ernie. With his left hand, he plucks the cigarette from his lips, the trail of smoke following its way into the rice cooker as it’s put out into the still warm rice. He laughs, and asks for another beer.

Maybe that night you realized yourself as a poet. Your young life the poem being set into the tradition of the immigrant story.

The alcohol already flowing inside you, you try to pull your new friends out from the fray and the swinging limbs, but a stray fist lands clean into your temple. For a second, the combatants turn to look at you, the look of betrayal at someone who looks just like them. You’re supposed to be with us, the expressions clear in their faces. But instead, you tackle an unknown body and bring him to the ground, and begin raining fists. His friends join in almost immediately, stomping at your back, and at one point, a bottle shatters against the back of your neck. But you don’t stop. Your victim’s face is already pleading, his arms feebly suspended in front of him.

T.S. Eliot once said, in speaking to new forms of art, “that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past. And the poet who is aware of this will be aware of great difficulties and responsibilities.”

Maybe that night you realized yourself as a poet. Your young life the poem being set into the tradition of the immigrant story. Maybe that night you remembered how the mind unhinges itself in the throes of death, how your papa couldn’t remember who you were, that at our core is only rage.

Maybe you thought, how impossible it is to alter the past, because, the truth is, the past won’t remember you, and that violence is the true expression of grief.

* * *

Only two years before I am born, you are in your room, that same heathen sanctuary that terrified your mom. The same scene that has pervaded your life so far: the Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin posters peeling off the drywall, a forty in your hand, and its predecessors on your dresser. But on this day, in the other hand is a .38 Special, like the ones introduced in the Philippine-American War to puncture the ranks of the Filipino army. You think of the band with the same name, how you kind of like “Caught Up In You,” but it’s nothing like “Free Bird.”

You grab a single round from the floor and load it in the chamber. You take a heavy swig and feel that amber wave numb you.

What is that scene from Deer Hunter? You recollect as if in prayer, playing it out in your head, imagining the sweaty Vietnamese soldier slapping you across the face. Mao! Mao! he yells. Across from you is Robert DeNiro, telling you that you got an empty chamber in that gun. But the little bastard keeps slapping you. Mao.

The scene is tense. The pause, humid and thick, as tears begin to roll down.

Actual tears, not just ones acted out, form against your cheek. I don’t want to die. It’s clear to you that you just want to live, as you grip the trigger with determination. Then with a quick flick of the wrist, you aim the barrel at the imaginary Commies in front of you. You are the American war hero as you mow them down. You refuse to play the game.

But as you take a triumphant pull from the bottle, the gun goes off and the bullet straight through your leg. Suddenly, you are on the ground trying to avoid the ricochet, but you feel your thigh, now an infinite thing of pain, like something expanding into the universe itself.

The pistol does what it was designed to do. To stop our people from resisting America.

You scream, and your family—your mom thinking a demon has truly inhabited your room—charges through the door and rushes you to the county hospital.

On that day, you learn that our wounds are not truly American unless they are self-inflicted.

* * *

The season is young, but on this April evening in ‘92, the Dodgers are already down six-zero to the Phillies. The Bulldog has been chased out after a five-run 4th; the benches are somber, glazed eyes staring out across the diamond—that pinnacle of American Zen—Lasorda salvaging what is left of ‘88.

On the scoreboard, an announcement is made that riots had begun to spread throughout parts of South LA and into Koreatown, less than ten miles from the ravine.

In the final innings, the stadium has already cleared out, as if it had only been an exhibition game, the fans praying their homes aren’t smoldering by the time they arrive. From the top of the ravine, the fires below look like erupting blisters, the flashing sirens like embers streaming toward its source. And up on the hill, it was the one night where baseball was only a spectator.

* * *

It is not just you, but we, the young family learning firsthand that conflict drives the narrative of America. Our lives gravitate towards these nights of assault and arson. Grandma has given up the master bedroom in the back of the house and taken your old room, with not enough holy water and prayer to exorcise what demons you’ve left in there.

On the nights of the riots, the city begins enforcement of road closures and curfews. From the stadium, there is a sense of a city drowning. The smoke and sirens are only tremulous to the senses, as if you are looking up from the bottom of a lake.

You’re glued to the news, examining each aerial shot of the city like it’s a work of art. You know all about King and the verdict, even explaining to your mom that the pigs deserve this shit as she tries to pray for the city through the TV.

I am on the other side of the room with a piece of red fabric tied around my head. Where I got it, I will never know, probably from mom’s closet. Since you are watching the news, I am continuing the legacy of Ryu from Street Fighter. The room is still as you watch the news, and mom is flipping through a magazine on the bed. But here I am, ducking shoryukens and shooting out hadoukens against the air in front of me. I jump up and fall down, stunned by Blanka’s overpowered electricity. I clutch my hand to my chest, wiping blood off my mouth, because that’s how I think wounds work.

Hey, kupal, be careful, you say as you extend a leg out toward me.

You are flipping the balisong in your hand. You’ve sworn off guns, but still stay armed. As removed as we are, we will always have the weapons of our past.

Mom walks over to you, and I try to land a leg sweep as she comes into my arena. She casually avoids me, and proceeds to wrap her arms around you and asks how bad it’s gotten, watching the screen flicker from fire to fire, then to a white man being dragged from a truck and beaten.

Dodgers GM Dave Roberts, half black and half Japanese, said in an interview twenty-five years later, I’m not saying I felt like I had to pick a side but by that time, my race, my awareness, I looked more closely at who I was.

And on that same night, you turned around to face mom, and you asked her, What side should we be on? If we had to choose, we’d be better off with the Mexicans. I think the Blacks would try to kill us.

I stopped moving for a moment after you said this.

Of course, I had no idea what you were talking about, but now, suddenly in the midst of my own moment, in the midst of the alt-right and race wars that now flare up in every corner, in the midst of anti-intellectualism and conspiracy theories, and now as I put your ashes in the granite slab, I remember Baldwin: An identity is only questioned when it is menaced.

* * *

In the summer, something defiant emerges from the hills that look like the drying pelts of mountain lions. It is the chaparral yucca, also known as the Spanish bayonet, the Quixote yucca, and Our Lord’s candle. The weapon, the illusion, the vigil.

The spike of its stem blooms from a cluster of serrated leaves at its base, and as I drive along the freeways, the yuccas look like fireworks suspended in mid-propulsion.

* * *

I am remembering your collection of baseball cards, long boxes lined neatly in the closet of every place we moved to. Ken Griffey Jr. and Mike Piazza rookie cards tucked inside protective sleeves. Everyone from Barry Bonds to recalled utility players.

I am remembering the time at the comic book store when you bought several copies of The Death of Superman. The issues inside black sleeves with only a blood red emblem on the front. In the future, these are going to be worth a lot, anak.

But what is the death of our fictional heroes worth?

What is the value of a fictional death versus the real thing?

I am remembering what you had told me after I got expelled from school for fighting. If you ever get in a fight and you’re outnumbered, just pick one. Hold on to one and don’t let him go. Even if you get jumped, you’ll still take out one. Just don’t let go.

After mom left, you threw out the baseball cards, their boxes sticking out of the dumpster like broken slabs of concrete. They’re too heavy for me to carry now. And we’re getting evicted this week.

These cards, lost in some landfill or maybe even dug up and sold, only projections as I search the last duffle bag you carried with you. Instead, I am finding books on manic depression and the books I recommended to you in grad school. Your journals filled with vocab words, the same ones you’d use when you’d text me, words like ameliorate and conflagration.

But there are no baseball cards left.

* * *

I am remembering our fight on the balcony of your apartment. Even as your body waned, its muscle memory still retained its ferocity. Who the fuck do you think you are? you yelled, as if lashing out from inside a cage. In desperation or rage or both, for those few moments, I couldn’t remember who you were.

* * *

In the hospital, before you underwent surgery, before you would lapse into a coma as blood began to drain into your skull, I had brought some food and a card in what I didn’t know would be our last conversation.

Dad, this is the hardest part. Remembering the last time we spoke. The last time language meant anything between us. How the conversation was carried by your questions, and me giving you as much as I knew.

To think, now, that the vitality of language is only felt through memory.

Because we don’t remember what was said until one can no longer say it.

What is the use of a question without someone to listen?

Almost every night now, I cauterize my jaws shut. Our melancholy, this weight—as Ginsberg once put it, this love—grinding and pressurizing my teeth into dust.

The doctor traced the images of your head on the monitor, all the way down your amygdala, the involuntary, instinctual functions. He won’t be able to support himself on his own, he said. The damage and the fluid are just irreparable at this point.

They say curse words are stored in this region, apart from the rest of our language centers in the prefrontal cortex. They also say that cursing helps deal with pain.

But that night you died, high on morphine like a true child of Zeppelin and Sabbath, it was only me, on the other side of the room, cursing, begging. Words that are supposed to help with pain, only felt like its amplifiers. Screaming questions guttural and primal, as if I had been attempting to commune with the urtext of loss. The pastel beige and blue curtains, a veil through which my voice could not carry.

There you were, silent, when you left.

Almost every night now, I cauterize my jaws shut.

Our melancholy, this weight—as Ginsberg once put it, this love—grinding and pressurizing my teeth into dust. My wife, distraught by the intensity by which I am crushing myself, will shake me, and I wake up as if being resuscitated from drowning.

* * *

It was in the true grip of summer—the marine layer becoming a suffocating weight—when you visited my apartment. My first true home, my first true feeling of home, since our cul-de-sac dream in the desert.

After I gave you the tour, gleaming pride in showing you my bookshelves and the couch my wife bought for the place, the first thing you did was take a nap on that couch. Your body taut, used to minimizing yourself for so many years after your divorce, learning the ways in which to make yourself invisible. But I watched you, and noticed your face, juxtaposed alongside your rigid limbs with a serene expression.

I still like to think that, even for those few minutes, you succumbed to that same feeling we all lost so long ago. Maybe you did feel at home.

When you woke up, you asked for some water. Then asked for more. Through every sip, you studied the pictures on the fridge as if they were ancient runes on a monolith. Our dog, still a puppy, before he would lose an eye after being attacked by strays. My sister, with the wild mane that mirrors yours, hugging him. A picture of me in kindergarten, posing in a karate stance.

You laughed. You’re still stupid, anak. I remember when you were a baby and I’d carry you outside, whenever a skateboarder would go by, you’d follow them with your mouth open. Drooling. We thought something was wrong with you.

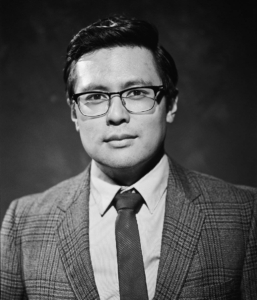

I find the picture in your bag. This frozen capsule of our lives, of you holding me.

You, only twenty-seven, with the suave pride of your newfound fatherhood captured in the old Polaroid. And me. You weren’t wrong about me.

I imagine then, as if the image suddenly takes life, the sounds of the skateboard. My head bumbling and bobbing as it goes by. I can hear your laugh. Even in your youth, it is the same laugh I will hear when I tell you one last joke before the encephalitis shuts down your motor functions, before your jaw goes slack as they insert the respirator tubes, before your hands lie limp and swollen and no longer able to hold mine.

That day in my apartment, you had asked me, So, when are you having kids?

I replied with hesitance, with the usual response of not being ready. Not knowing if I’d ever be ready.

But then your brow narrowed. You took another sip, as if preparing yourself for your final commandment.

Anak, trust me. It’s easy to love your kids. Once they show up, being a father is the easiest thing to do. Because you’ll love your kids without question.

I feel the years suddenly strip away from me. My degree, my salary, my life, my pride. A hammer striking porcelain. A bullet shattering bone. I forget sometimes how close I am to the edge, but that day I remembered.

What it must have been like to be something unfettered, undeniable in America. Your refusal to lie in the mire of what you saw as the immigrant. To feel the American berserk injected into you with every concert, with every hit, with every girl, with every time you turned your back on your pain and your past. Initiated into the new reality of a foreign land, apart from the obsequious tenure of our people.

On the news, journalists are unearthing the children in the immigrant detention centers. These children, knowing little, if any, English, are treated as though vermin, as though a trap has been sprung beneath their feet. Even if their bodies endure, everyone on the other side of the cage will be witness to the deaths of their spirit.

I want to see your face contort in disgust as I tell you about this. I want to hear the familiar rage in your voice and I want it to resonate in my heart, to defibrillate what is perpetually dying in my complacency. I pick up my phone and my eyes drift to the date of your last text. The theories I learned in school, the abstractions strewn across whiteboards now pale to what faces me now. As I read the words—What time are you coming by?—they reveal something as simple as it is terrifying.

The ghosts of language are the words that cannot echo with a reply.

Then here I am. Your son. You are a father, as you carry me to the park and watch as I chase birds and try to eat dirt. Your previous life I would never know about, even though I always asked. Always keeping sacred your role of father.

* * *

After the yucca is pollinated, it dies. But even years after, its stalk, and the kinetic flowers that crown it, remain upright.

Even in death, we create our own effigies.

* * *

In Tagalog, there is no word for son or daughter. The word for a child is not the same.

What exists is anak.

In the frailty of the English term, son or daughter is simply a title, a position of rank in the nuclear family.

But anak exists as a state of being. The same way the verbs such as am or be are used.

Because for us, being a son or daughter is not a title, but a way of existing in this world, even when you are no longer here. To be an anak is to always navigate the way home through the tether of family, despite years, despite failure. Humility in inexperience, and comfort in seeking guidance. A belonging.

Today, I sat beside your grave and cried as the planes overhead shook the ground. I asked if you were some kind of spirit and a branch hit me in the back.

And as I remember you, I understand something about myself.

I will always be the one watching the world while you hold me and laugh.

Finally, I understand what it means to be your anak.

Jordan Guevara is a native Angeleno who was raised in Filipinotown. He earned his MA in creative writing from Cal State Northridge where he taught Asian-American studies and English for a brief period. His work has been previously published in Chaparral and The Northridge Review. Jordan frequently delves into science fiction and capturing the voice of the API in the 21st century, which he has presented at conferences across the country. He’s also an avid Dodgers fan and gamer. Jordan lives in Los Angeles with his wife and tuxedo cat.