Seven Poems by Humberto Ak’abal

Las Flores

Las raices

nos mandan a contar

—por medio de las flores—

cómo es la tierra por dentro.

Y las flores se marchitan,

se mueren

porque acá afuera

la vida es una mierda.

Prayer

In church

the only prayer you hear

comes from the trees

they turned into pews.

Oración

En los templos

sólo se oye la oración

de los árboles

convertidos en bancas.

Birth

Poets are born old:

as the years pass

we make ourselves

into children.

Nacimiento

Las poetas nacemos viejos:

con el paso de los años

nos vamos haciendos niños.

A Person

A sad person

is not a person.

It’s just a shard

of something

walking along

with half a life.

Una persona

Una persona triste

no es una persona.

Es un pedazo de algo

que camina

con la mitad de la vida.

Awakening

One day

the Creator saw me alone,

so alone.

He made me sleep,

he made me dream

out in the fields of maize,

and he wrenched a rib out of me…

Upon waking,

in front of me

—gorgeous, naked, made of clay and corn,

scented like a mountain—

my poetry.

Al Despertar

Un dia

el Creador me vio sólo,

muy sólo.

Me hizo dormir,

me hizo soñar,

bajo una mata de milpa

y me arrancó una costilla…

Al despertar,

frente a mi

—rechula, desnuda, de barro y de maiz,

con olor a monte—

mi poesía.

Jaguar

Sometimes I’m a jaguar

running through ravines,

leaping boulders,

climbing mountains.

I look beyond the sky,

beyond the water,

beyond the earth.

I chat with the sun,

play with the moon,

and pluck stars

and stick them to my body.

My tail stirs as I

stretch out on the grass,

tongue panting.

Jaguar

Otra veces soy jaguar,

corro por barrancos,

salto sobre peñascos,

trepo montañas.

Miro más allá del cielo

más allá del agua,

más allá de la tierra.

Platico con el sol,

juego con la luna,

arranco estrellas

y las pego a mi cuerpo.

Mientras mueve la cola,

me hecho sobre el pasto

con la lengua de fuera.

Freedom

Blackbirds, buzzards, and doves

perch on cathedrals and palaces

the same as rocks,

trees, and fence posts,

and they shit on them

with the full freedom of those who know

that god and justice

live in the soul.

Libertad

Sanates, zopes, y palomas

se paran sobre catedrales y palacios

tan igual como sobre piedras,

árboles y corrales…

y se cagan sobre ellos

con todo la libertad de quien sabe

que dios y la justicia

se llevan en el alma.

Translator’s Statement

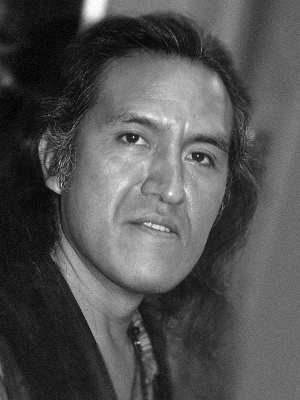

Humberto Ak’abal (1952-2019) was a K’iche’ Mayan poet born in Momostenango, in the western highlands of Guatemala. The highlands are lush, with mountains covered in cloud forest, the trees draped with bromeliads and furred with moss, well adapted to taking a sip from the sideways-drifting morning fog. The connection to place in Ak’abal’s work is palpable; the language seems to arise from the land itself, where stones speak, wooden benches remember being trees, and there is laughter in a rain shower. As Ak’abal himself said: “My words hold the dampness of rain, /the tears of morning dew, and it cannot /be otherwise, because they were / brought down from the mountain.”

This connection to land via language calls to mind the great epic of the K’iche’ Maya, The Popol Vuh, when it came time for the gods to create the world: “it only took a word. / To make earth they said, ‘Earth’ /and there it was: sudden / as a cloud or mist unfolds / from the face of a mountain, / so earth was there.” An entire theory of language is embedded in this mythic moment, when words are not labels, like post-it notes, to be affixed to what they name. In this cosmogony of the K’iche’, words are a form of energy—tethered intrinsically to the thing they call forth—and as such they are not imposed by humans upon the landscape, but instead uncovered through careful listening and observation of the world around us.

Given language’s ability to summon, it perhaps comes as no surprise that the Popol Vuh’s ultimate test of what makes people truly human is their ability to name, with accuracy and gratitude, the ones who brought them into being and the place from which they come.

Ak’abal’s work does just this, with clarity and subtlety. It has an essential, almost elemental simplicity that can make it a bit tantalizing to translate. There is an immediacy to the poems, and a colloquial straightforwardness to the diction that allows the reader to quickly grasp the initial sense of the moment. Yet, there is an ineffable quality to the work that remains elusive, a sensibility that mixes playful, earthy observations with musings on time and memory that evoke Heraclitus: “watching how the water leaves / and how the river stays.”

Given that, for the most part, Ak’abal wrote in K’iche’ and then translated himself into Spanish, there is a duality to his poetry with different cadences bridging the colonial divide with a contraconquista energy. So, there is a completely different cultural syntax at play here. K’iche’ Maya has no verb to be. Past, present and future often coexist simultaneously and dream and memory intermingle. This may feel strange to a sensibility marinated in a sequential construct of time.

Ak’abal’s work is widely known in Guatemala and has been translated into over a dozen languages. His book, Guardián de la caída de agua (Guardian of the Waterfall), received the Golden Quetzal award from the association of Guatemalan Journalists. In 2004, he declined to receive the Guatemalan National Prize in Literature because it was named for Miguel Ángel Asturias, whom Ak’abal accused of encouraging racism. And claimed that his views on eugenics and assimilation: “offend the indigenous population of Guatemala, of which I am part.” In 2006, he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship.

I’m grateful to his family, particularly his wife Mayulí, for their support and encouragement in this endeavor. My hope is that these translations might help Ak’abal’s poems find a broader audience in English so that readers might, as Carlos Montemayor put it, “penetrate that other reality that we do not know, and understand. . .that this indigenous soul lives and breathes in our own reality at the same time as our time, with the same life as our life, loving and understanding the same continent that we love but do not understand.”

Humberto Ak’abal (1952–2019) was a K’iche’ Maya poet from Guatemala. His book Guardián de la caída de agua (Guardian of the Waterfall) was named book of the year by Association of Guatemalan Journalists and received their Golden Quetzal award in 1993. In 2004, he declined to receive the Guatemala National Prize in Literature because it is named for Miguel Ángel Asturias, whom Ak’abal accused of encouraging racism. Ak’abal, a recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, passed away on January 28th, 2019.

Michael Bazzett is the author of four collections of poetry, including his most recent, The Echo Chamber (Milkweed, 2021). His poems have appeared in The American Poetry Review, The Threepenny Review, The Sun, The Nation, Copper Nickel and Granta. His verse translation of the Mayan creation epic, The Popol Vuh (Milkweed, 2018), was long-listed for the National Translation Award and named one of the best books of poetry in 2018 by the New York Times. Find out more at michaelbazzett.com.