The Toad

[translated poetry]

What do we know? Who then understands the depths of things?

The sunset glowed in the rose-hued clouds.

It was the end of a day of storms, and the west

Set the showers aflame in a ferocious blaze.

Near a ditch, at the edge of a rain puddle,

A toad looked at the sky, dazzled creature.

In solemn contemplation, horror considered the splendor.

(Oh! Why is there suffering and why is there ugliness?

Alas! The Roman Empire is littered with petty Augustuses

Tyrannous Caesars, as the toad is with pustules,

As the meadow with flowers and the sky with sunshine.)

The leaves were purpling in the vermillion trees.

The water glinted, twined with the grass in the ditch.

The evening unfurled as a banner.

The bird lowered its voice in the weakening day.

All softened, in the air, on the horizon; and, full of forgotten dreams,

The toad, without fear, without shame, without anger,

Gentle, watched the enormous solar aureole.

Maybe the damned one felt blessed.

There’s no creature who cannot see a reflection of the infinite.

No eye so abject and vile that it does not touch

The light above, sometimes tender, sometimes shy;

No cringing monster, bleary, louche, impure,

Who does not have the heavens’ immensity in its eyes.

A man passing by saw the hideous creature,

And shuddering, stepped on the toad’s head.

It was a priest with a book he was reading.

Then a woman, with a flower on her lapel,

Came and poked out the toad’s eye with her umbrella.

And the priest was old, and the woman was beautiful.

Then came four schoolboys, serene as the heavens.

—I was a child, I was young, I was cruel—

All men on earth, where their subjugated souls wander,

Can start the story of their lives this way.

We have game, inebriated by the dawn in our eyes.

We have our mothers. We are joyous schoolboys.

Gay little men, breathing the air,

Filling our lungs, loved, free, and happy. What to do;

If not torture a pathetic being?

The toad crawled along in the bottom of a rut.

It was the hour when the far fields turn azure.

Wild creature, the toad longed for night. The children saw him.

They cried out, “Kill the disgusting animal. And he’s so ugly, let’s hurt him a lot.”

And each one of them, laughing—children laugh when they kill—

Began to stab at him with a pointed stick.

Enlarging the hole where his eye had been, wounding

His wounds, thrilled, applauded by the passersby;

Because the passersby laughed. And the sepulchral shadow

Covered the dark martyr who could not even moan.

And the blood, the atrocious blood, flowed from everywhere

On the poor creature, whose crime was to be ugly.

He fled. He had one leg torn off.

A child struck him with a broken trowel,

And every blow skimmed the beleaguered beast

Who, even on a day that smiled upon him,

Even beneath an immense sky, lurked at the bottom of a cave.

And the children said: “Is he mean! He drools!”

His forehead bled, his eye hung out; in the scrub

And brush, hideous to see, he made his way.

We might have said that he had escaped a terrible embrace.

Oh! The sorry act! To worsen misery!

To add horror to deformity!

Dislocated, he stumbled from stone to stone.

The toad still had breath, without shelter, without asylum.

He crawled. We might have said that death

Found him too ugly and refused to take him.

The children wanted to tie him in a shoelace,

But he escaped them, slipping beside a hedge.

The rut gaped. He dragged his wounds

And dived in, bloodied, broken, his skull open,

Feeling the bit of freshness in the green swamp,

Washing the human cruelty in the mud.

And the children, with spring on their cheeks,

Blonde, charming, had never had such fun.

They all talked at once, from the big to the little

Crying out: “Come see! C’mon Alfred, c’mon Peter

Let’s finish him off with a big stone!”

All together, they fixed their gaze upon the being

Beset by chance. And the despairing creature

Watched as their terrible faces hunched over him.

—Alas! Let’s have ideals; let’s not have targets.

When we set our sights on humanity’s horizon,

Let us hold life, and not death, in our hands—

All eyes followed the toad in the mud.

It was a furor and it was an ecstasy.

One of the children returned with a brick.

Heavy, but for its evil purpose easily carried.

He said: “We’ll see how this will be done.”

But, in the same moment, on this very spot of earth

Chance delivered a heavy cart

Pulled by an old, lame donkey, skin and bones and deaf.

This exhausted donkey, limping and appalling,

Was close to the stable after a day of walking.

He pulled the cart and carried a saddlebag.

Every step he took, as if his next to last.

The beast walked, beaten, extenuated.

The blows enveloped him like a clouded mist.

His eyes were veiled with a vapor

Of that stupidity, which is perhaps stupor.

And the rut was deep, and so full of mud,

And a slope so sharp that every turn of the wheel

Was like a dismal and hoarse tearing.

And the donkey went on, moaning, and the master cursed.

The road descended and pushed the pack animal

The donkey retreated into his thoughts, passive beneath the whip, beneath the flog;

Sunk to a depth where no human can go.

The children, hearing the wheel and the clop

Turned noisily and saw the cart.

“Don’t drop the brick on the toad. Stop!”

They cried. “Do you see, the cart will come down

And crush him as it passes. That will be so much more amusing.”

All watched.

Then, advancing in the rut,

Where the monster awaited his final torture,

The donkey saw the toad. And, sad—alas! Bent

Upon one sadder still—heavy, broken, mournful and scabrous,

He seemed to sniff with his head low.

This enslaved one, this damned one, this patient one, granted grace.

He gathered all his spent strength. And, stiffening

His chain and harness on his bloodied muscles,

Resisting his master who cried: “Go on!”

Taking the full measure of the terrible burden of his complicity,

In his weariness, accepting the fight;

He pulled the cart and lifted the saddle.

Haggard, he turned the inexorable wheel,

Leaving behind him the miserable toad to live.

Then, under the blow of the whip, he continued on his way.

So, letting the stone drop from his hand,

One of the children—the one who tells this story—

Under the infinite arched expanse that is at once blue and black,

Heard a voice that said to him: “Be good.”

Goodness of the fool! Diamond in coal!

Blessed enigma! Glorious light of the shadows!

The heavenly ones are no better than the doomed,

If the doomed, though blind and punished,

Think, and having no joy, yet have pity.

O sacred spectacle! The shadow saves the shadow.

The lost soul rescues the dark soul.

The stupid, moved to compassion, bends toward the hideous.

The good damned one awakens the chosen wicked one’s dreams.

The beast advances where the man recoils

In the serenity of the pale twilight.

The brute by turns thinks and feels she is sister

Of the mysterious and profound sweetness.

It is enough for a flash of grace to shine in her,

For her to equal the eternal star.

The beast of burden who, returning in the evening, weighed down, weary,

Dying, feeling its flat hooves bleed,

Takes a few extra steps, moves away and disrupts its course

To avoid crushing a toad in the mire.

This abject donkey, dirty, bludgeoned beneath the stick,

Is more holy than Socrates and greater than Plato.

You search, philosopher? O great thinker, you meditate?

Do you want to find what is real beneath our cursed fogs?

Believe, cry, lose yourself inside an immense love!

Whoever is good sees clear at the obscured crossroads.

Whoever is good inhabits a corner of heaven. O wise one,

The kindness, which in the world lights up a face;

The kindness, that gaze of the sweet morning;

The kindness, pure ray that warms the stranger;

The instinct that in the night and in suffering loves;

Is the ineffable and supreme link

That joins, in the gloom, alas!

The great innocent, the donkey, to God, the great sage.

![]()

Le Crapaud

Que savons-nous ? qui donc connaît le fond des choses ?

Le couchant rayonnait dans les nuages roses ;

C’était la fin d’un jour d’orage, et l’occident

Changeait l’ondée en flamme en son brasier ardent ;

Près d’une ornière, au bord d’une flaque de pluie,

Un crapaud regardait le ciel, bête éblouie ;

Grave, il songeait ; l’horreur contemplait la splendeur.

(Oh ! pourquoi la souffrance et pourquoi la laideur ?

Hélas ! le bas-empire est couvert d’Augustules,

Les Césars de forfaits, les crapauds de pustules,

Comme le pré de fleurs et le ciel de soleils !)

Les feuilles s’empourpraient dans les arbres vermeils ;

L’eau miroitait, mêlée à l’herbe, dans l’ornière ;

Le soir se déployait ainsi qu’une bannière ;

L’oiseau baissait la voix dans le jour affaibli ;

Tout s’apaisait, dans l’air, sur l’onde ; et, plein d’oubli,

Le crapaud, sans effroi, sans honte, sans colère,

Doux, regardait la grande auréole solaire ;

Peut-être le maudit se sentait-il béni,

Pas de bête qui n’ait un reflet d’infini ;

Pas de prunelle abjecte et vile que ne touche

L’éclair d’en haut, parfois tendre et parfois farouche ;

Pas de monstre chétif, louche, impur, chassieux,

Qui n’ait l’immensité des astres dans les yeux.

Un homme qui passait vit la hideuse bête,

Et, frémissant, lui mit son talon sur la tête ;

C’était un prêtre ayant un livre qu’il lisait ;

Puis une femme, avec une fleur au corset,

Vint et lui creva l’œil du bout de son ombrelle ;

Et le prêtre était vieux, et la femme était belle.

Vinrent quatre écoliers, sereins comme le ciel.

– J’étais enfant, j’étais petit, j’étais cruel ; –

Tout homme sur la terre, où l’âme erre asservie,

Peut commencer ainsi le récit de sa vie.

On a le jeu, l’ivresse et l’aube dans les yeux,

On a sa mère, on est des écoliers joyeux,

De petits hommes gais, respirant l’atmosphère

À pleins poumons, aimés, libres, contents ; que faire

Sinon de torturer quelque être malheureux ?

Le crapaud se traînait au fond du chemin creux.

C’était l’heure où des champs les profondeurs s’azurent ;

Fauve, il cherchait la nuit ; les enfants l’aperçurent

Et crièrent : « Tuons ce vilain animal,

Et, puisqu’il est si laid, faisons-lui bien du mal ! »

Et chacun d’eux, riant, – l’enfant rit quand il tue, –

Se mit à le piquer d’une branche pointue,

Élargissant le trou de l’œil crevé, blessant

Les blessures, ravis, applaudis du passant ;

Car les passants riaient ; et l’ombre sépulcrale

Couvrait ce noir martyr qui n’a pas même un râle,

Et le sang, sang affreux, de toutes parts coulait

Sur ce pauvre être ayant pour crime d’être laid ;

Il fuyait ; il avait une patte arrachée ;

Un enfant le frappait d’une pelle ébréchée ;

Et chaque coup faisait écumer ce proscrit

Qui, même quand le jour sur sa tête sourit,

Même sous le grand ciel, rampe au fond d’une cave ;

Et les enfants disaient : « Est-il méchant ! il bave ! »

Son front saignait ; son œil pendait ; dans le genêt

Et la ronce, effroyable à voir, il cheminait ;

On eût dit qu’il sortait de quelque affreuse serre ;

Oh ! la sombre action, empirer la misère !

Ajouter de l’horreur à la difformité !

Disloqué, de cailloux en cailloux cahoté,

Il respirait toujours ; sans abri, sans asile,

Il rampait ; on eût dit que la mort, difficile,

Le trouvait si hideux qu’elle le refusait ;

Les enfants le voulaient saisir dans un lacet,

Mais il leur échappa, glissant le long des haies ;

L’ornière était béante, il y traîna ses plaies

Et s’y plongea, sanglant, brisé, le crâne ouvert,

Sentant quelque fraîcheur dans ce cloaque vert,

Lavant la cruauté de l’homme en cette boue ;

Et les enfants, avec le printemps sur la joue,

Blonds, charmants, ne s’étaient jamais tant divertis ;

Tous parlaient à la fois et les grands aux petits

Criaient : «Viens voir! dis donc, Adolphe, dis donc, Pierre,

Allons pour l’achever prendre une grosse pierre ! »

Tous ensemble, sur l’être au hasard exécré,

Ils fixaient leurs regards, et le désespéré

Regardait s’incliner sur lui ces fronts horribles.

– Hélas ! ayons des buts, mais n’ayons pas de cibles ;

Quand nous visons un point de l’horizon humain,

Ayons la vie, et non la mort, dans notre main. –

Tous les yeux poursuivaient le crapaud dans la vase ;

C’était de la fureur et c’était de l’extase ;

Un des enfants revint, apportant un pavé,

Pesant, mais pour le mal aisément soulevé,

Et dit : « Nous allons voir comment cela va faire. »

Or, en ce même instant, juste à ce point de terre,

Le hasard amenait un chariot très lourd

Traîné par un vieux âne éclopé, maigre et sourd ;

Cet âne harassé, boiteux et lamentable,

Après un jour de marche approchait de l’étable ;

Il roulait la charrette et portait un panier ;

Chaque pas qu’il faisait semblait l’avant-dernier ;

Cette bête marchait, battue, exténuée ;

Les coups l’enveloppaient ainsi qu’une nuée ;

Il avait dans ses yeux voilés d’une vapeur

Cette stupidité qui peut-être est stupeur ;

Et l’ornière était creuse, et si pleine de boue

Et d’un versant si dur que chaque tour de roue

Était comme un lugubre et rauque arrachement ;

Et l’âne allait geignant et l’ânier blasphémant ;

La route descendait et poussait la bourrique ;

L’âne songeait, passif, sous le fouet, sous la trique,

Dans une profondeur où l’homme ne va pas.

Les enfants entendant cette roue et ce pas,

Se tournèrent bruyants et virent la charrette :

« Ne mets pas le pavé sur le crapaud. Arrête ! »

Crièrent-ils. « Vois-tu, la voiture descend

Et va passer dessus, c’est bien plus amusant. »

Tous regardaient.

Soudain, avançant dans l’ornière

Où le monstre attendait sa torture dernière,

L’âne vit le crapaud, et, triste, – hélas ! penché

Sur un plus triste, – lourd, rompu, morne, écorché,

Il sembla le flairer avec sa tête basse ;

Ce forçat, ce damné, ce patient, fit grâce ;

Il rassembla sa force éteinte, et, roidissant

Sa chaîne et son licou sur ses muscles en sang,

Résistant à l’ânier qui lui criait : Avance !

Maîtrisant du fardeau l’affreuse connivence,

Avec sa lassitude acceptant le combat,

Tirant le chariot et soulevant le bât,

Hagard, il détourna la roue inexorable,

Laissant derrière lui vivre ce misérable ;

Puis, sous un coup de fouet, il reprit son chemin.

Alors, lâchant la pierre échappée à sa main,

Un des enfants – celui qui conte cette histoire, –

Sous la voûte infinie à la fois bleue et noire,

Entendit une voix qui lui disait : Sois bon !

Bonté de l’idiot ! diamant du charbon !

Sainte énigme ! lumière auguste des ténèbres !

Les célestes n’ont rien de plus que les funèbres

Si les funèbres, groupe aveugle et châtié,

Songent, et, n’ayant pas la joie, ont la pitié.

Ô spectacle sacré ! l’ombre secourant l’ombre,

L’âme obscure venant en aide à l’âme sombre,

Le stupide, attendri, sur l’affreux se penchant,

Le damné bon faisant rêver l’élu méchant !

L’animal avançant lorsque l’homme recule !

Dans la sérénité du pâle crépuscule,

La brute par moments pense et sent qu’elle est sœur

De la mystérieuse et profonde douceur ;

Il suffit qu’un éclair de grâce brille en elle

Pour qu’elle soit égale à l’étoile éternelle ;

Le baudet qui, rentrant le soir, surchargé, las,

Mourant, sentant saigner ses pauvres sabots plats,

Fait quelques pas de plus, s’écarte et se dérange

Pour ne pas écraser un crapaud dans la fange,

Cet âne abject, souillé, meurtri sous le bâton,

Est plus saint que Socrate et plus grand que Platon.

Tu cherches, philosophe ? Ô penseur, tu médites ?

Veux-tu trouver le vrai sous nos brumes maudites ?

Crois, pleure, abîme-toi dans l’insondable amour !

Quiconque est bon voit clair dans l’obscur carrefour ;

Quiconque est bon habite un coin du ciel. Ô sage,

La bonté, qui du monde éclaire le visage,

La bonté, ce regard du matin ingénu,

La bonté, pur rayon qui chauffe l’inconnu,

Instinct qui, dans la nuit et dans la souffrance, aime,

Est le trait d’union ineffable et suprême

Qui joint, dans l’ombre, hélas ! si lugubre souvent,

Le grand innocent, l’âne, à Dieu le grand savant.

Translator Note

My translation process is unique. I began my study of the text in French from a performance perspective. Working with a theatre professional in Paris (in person when I am there and via Skype when I am in the US), I honed the performance of the text in its original language. The result is an embodied approach to understanding the deep roots of the text and its emotional resonance in the body. Once I have fully explored the text from this angle, only then do I begin to translate. My aim is to preserve the old world flavor of the texts, while at the same time bringing the message forward for our times, so that it is immediate and relevant. So I am working with the words on the page and the felt experience of the text in the body.

The texts I am translating have long been in the public domain. In the case of Victor Hugo’s long poem, “The Toad,” it is a poem which has only ever been translated once before in the 19th century, in a translation which is no longer available. Yet the poem’s exploration of casual cruelty and innocence is as urgent today as it was when Hugo wrote the piece.

Mina Samuels is a writer, playwright, and performer. Her books include, Run Like A Girl 365 Days: A Practical, Personal, Inspirational Guide for Women Athletes, Run Like a Girl: How Strong Women Make Happy Lives, and a novel, The Queen of Cups. She’s created and performed two award-winning solo shows and her ensemble play, Because I Am Your Queen, was produced at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts. She also posts weekly translations of Jean de La Fontaine’s 17th century French fables with contemporary commentary.

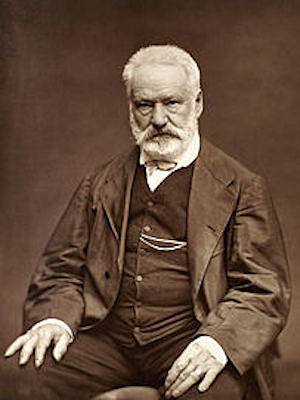

Mina Samuels is a writer, playwright, and performer. Her books include, Run Like A Girl 365 Days: A Practical, Personal, Inspirational Guide for Women Athletes, Run Like a Girl: How Strong Women Make Happy Lives, and a novel, The Queen of Cups. She’s created and performed two award-winning solo shows and her ensemble play, Because I Am Your Queen, was produced at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts. She also posts weekly translations of Jean de La Fontaine’s 17th century French fables with contemporary commentary.  Victor Marie Hugo (26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement. Hugo is considered to be one of the greatest and best-known French writers. Outside of France, his most famous works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, 1831.

Victor Marie Hugo (26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement. Hugo is considered to be one of the greatest and best-known French writers. Outside of France, his most famous works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, 1831.