Victoria Chang, Author, Poet, MFA Program Chair

Photo credit: Margaret Molloy

At the beginning of February, I had a phone interview with Victoria Chang, the program chair of the MFA program at Antioch University.

“Are you going to the community conversation tomorrow?” I asked her. Antioch was hosting a community meeting, organized by Women Who Submit, for #DignidadLiteraria, an activist group for Latinx authors/writers/artists for fair representation in publishing. The American Dirt fiasco had just happened, and one of Antioch’s alums and Women Who Submit cofounder, Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo organized a panel discussion to discuss the fallout.

“I’m driving down from Sacramento to be there,” I told her. “I’m coming at 3:00 in the afternoon and I’m hoping I’m going to get a seat.”

“Yeah,” Victoria said. “It’s going to be wonderful, but I hope we have enough room. We’re going to set up overflow, just in case. Xochi (Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo) planned this in one week, which is phenomenal. She called and said, ‘I need some space.’ So, by Monday we were working on getting space to host this. It’s going to be so great. Roxane Gay and Myriam Gurba will be there, and others.”

The meeting was fabulous, and the partnership between Chang and Bermejo made it all happen. As an Antioch student, I’ve observed Chang’s partnership with many other agencies that promote social justice close up. She has always argued that we all have to be literary citizens.

“You can’t be a writer without being a literary citizen,” she said. “A literary community functions like an ecosystem, and if you can’t function in an environment like that, you’re not going to be as great of a writer as you could have been.”

Chang enjoys her place inside a literary community, in every season—even the busy ones. As we caught up on the phone, we discussed the upcoming AWP Conference in San Antonio, the June 2020 residency, and her time at the Lannan Residency, from which she had just returned. Right before our phone call, she’d been reviewing scholarship applications for the Idyllwild Writer’s Week, a program she co-coordinates with her colleague, Ed Skoog. Chang also serves on the National Book Critics Circle Award, and does many other things.

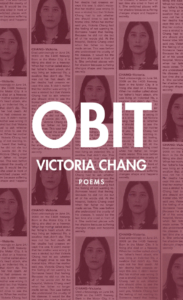

On top of it all, Chang’s newest book, OBIT (Copper Canyon Press 2020), was scheduled for release in April, and Chang had to adjust her previously scheduled readings, because of COVID19. “We all have to remain flexible,” she told me.

It seems appropriate that her new collection is poetry that revolves around themes of grief and loss. In OBIT, Chang writes of her mother, who died of pulmonary fibrosis in 2015, and her father, who suffered frontal lobe damage in 2009, using poetic forms that closely resemble newspaper obituaries. In between, Chang sprinkles tankas, Japanese forms that are as light as snowflakes. The balance of light and dark, death and life, show the beauty and sadness of a life where love is nurtured and then torn from us. Interviewing Victoria came right after I had just lost my beloved Nina, my Auntie Molly. The reason I was traveling down to Los Angeles was to pick up two of my Aunties in Southern California for the funeral. This is what set the stage for our discussion.

* * *

Janet Rodriguez: When someone asks you, “What is OBIT?” What do you say?

Victoria Chang: I once heard someone use the word “distill” and I liked it. It was like I was trying to distill grief and give language to something I knew would be impossible to describe. Ultimately, I think I failed, because you can’t really describe grief. I don’t think it’s possible. I think the fact that I sensed this was impossible is why I wrote the book [laughs]. I always like to be challenged.

I knew what I felt and what I thought, but I wondered how I could share that experience through language. When people have other people who they really care about die, all you hear is, “I’m really sorry for your loss…” and that’s it! You don’t sit around feeling really bad about what happened, it’s just a really horrible thing. It’s incredibly lonely. I read a lot of nonfiction books that helped me, which were really intense. I couldn’t find books of poetry that were written about grief that I fully connected to. So, I guess I was writing the poetry book that I would have wanted to read.

We grow up watching movies about death and how people die. It’s relatively quick. People die in their sleep and they just look so peaceful. I had no idea how violent death could be until you’re right there.

JR: How has grief changed you as a writer? As a person?

VC: The whole thing about grieving is complicated and fascinating, as a process. It’s all very tragic and sad, but I’ve learned to embrace it and learn from it.

For me, I think of myself as a naturally happy-go-lucky person, someone who is optimistic and expansive, but I have deep, deep moments of sadness. Being in that cloud of illness and death all the time has been a weird dichotomy. One minute, you’re bouncing around laughing, and the next moment, you’re weeping. So, it’s been the state of mind I’ve been in for a very long time. I’ve learned how to accept that, instead of always trying to be so tough, or always trying to be such a strong woman in a culture that is very misogynistic and very against women, and women of color, in particular. These experiences have allowed me to accept that side of myself, and say, “It’s okay. You can be weepy and sad. You can cry!” You can even be vulnerable, which is a new concept. I don’t really like to be vulnerable.

Maybe people look at me and think I’m fine, but I don’t feel fine. I’m always grieving. I’m always in a state of grief. Maybe it’s because my father is still sick. I’ve heard people tell me, people older than me, that when their last parent died, there was something that lifted. Maybe that’s what I’m feeling: that grief that’s still very present. On the other hand, I like visiting my father. He’s so funny now and it’s fun being his boss for a change!

JR: Your mother died of pulmonary fibrosis, and at the very beginning of the book, the poem “My Mother” begins with, “My mother died unpeacefully on August 3, 2015…,” which is powerful, but it shows how hard the disease is, doesn’t it?

VC: It is a very hard death. Plus, my mom was very secretive. For as long as I can remember, she had this hacking cough. She had it for almost fifteen years, and I always remember her coughing. Even before my dad had a stroke, it got worse. If we were walking and she’d start wheezing, I’d say, “Stop coughing! Stop wheezing! What’s wrong with you?” She would say, “Oh, I have allergies.” It took me awhile to realize she had a lung disease. Once I got the name, I spent time researching it. I checked out those forums and spent so much time reading what other people had written. People were saying that pulmonary fibrosis is the worst disease, and I realized how much people suffer by reading other people’s comments. It’s so slow! People literally suffocate to death. That was really hard to watch.

We grow up watching movies about death and how people die. It’s relatively quick. People die in their sleep and they just look so peaceful. I had no idea how violent death could be until you’re right there. Nobody ever talks about it, just like when I was growing up, nobody ever talked to me about money or menopause, but we can talk about television shows people are watching? Critics write long essays on movie stars… ad nauseum. Who cares? No one ever tells you, “Dying can be pretty hideous.” I don’t know if it’s because that sort of fear of dying oneself, you know? If you think too much about it, it can be scary. I think about it all the time, but that’s because I’ve lived it, and it was around me all the time.

If we were talking about your aunt and her death in a social setting, it wouldn’t scare me. Some people would be like, “Let’s not talk about this” [laughs]. I’m at the point of saying, “Let’s talk about this!” Most might want to change the topic.

JR: Yeah, because some people don’t want to be reminded of death or dying.

VC: But for me as a writer, this is how I process the world and navigate the world, so I have to put words to it. Words are everything. I didn’t really talk to anyone about it, but maybe that’s why I thought I needed to put words to paper.

JR: And life doesn’t just stop while all this is happening, does it?

VC: No, it doesn’t! As I was putting the book together, I was struggling with all these kid-related things. The poems of kids, the tankas in the book and the middle section, they’re all about life. I knew there’s a future for my children. There’s an implicit understanding that your kids are going to have a future in everything you do. Why am I making them study for this test? Most of the time I was thinking, “Who cares!” Because my mother was dying or my father was sick. Why do I care if my kid passes that test when there are greater things at risk? All these other parents, who were always around, seemed to be overly intense about this soccer game or that basketball game or this test or that test. I get it. I think I would have been as intense about sports and tests if death wasn’t hovering so close. Instead, I felt a sense of “None of this matters!” I had a fatalistic mentality which I’m sure has shaped my children and shaped my childrearing.

Sometimes, other parents around me seem very unforgiving. Sometimes, I get the sense that other people think I’m not social or don’t do enough sharing of social labor related to my kids but I don’t have a ton of capacity these days. In addition to running the Antioch program, I have a lot of other responsibilities, such as getting my father a wheelchair, scheduling doctor’s visits, or figuring out how to get the balls of ear wax out of his ears!

Also, I have a hundred other kids I’m responsible for, if you count my students at Antioch. You know something about that, right?

JR: [laughs] And we’re all needing different things from you! What’s it like to care for everyone else in the midst of all this?

VC: I think my life is really good, and I think I can do a lot, as long as there are not a lot of emotional stakes in the things I do. Normally, I don’t waste a lot of time on feelings—I save all of that for when I’m writing—but things happen at work, and student challenges can become emotional. I can feel beaten up a bit.

Our Provost recently said, “In a leadership position, sometimes people think it’s their job to unstuff your feathers.” It’s true! I’ve had my feathers unstuffed a fair amount since I’ve been the program chair at Antioch, sometimes rightfully, other times not, but that’s probably the biggest learning opportunity for me now. There’s emotional stuff that takes place at Antioch, and sometimes I don’t feel like I’m mentally prepared for it.

JR: Did you ever feel like all of this on your plate was hindering your writing process?

VC: You know, I read articles that say it’s really bad to bounce around a lot, and it’s bad for your brain, and you can’t focus, and maybe that’s true. I’m sure it might just be awful for me, but I don’t really feel it. I think I might be naturally attention-shifting, to use a euphemism, but I think that all the things I do are fun for me, which is why I do them. People who think it saps their energy to jump around and do a bunch of different things probably shouldn’t do it, but for me, it makes me happy because it’s who I am; otherwise, I wouldn’t do it.

So, my writing process can be very obsessive. When you’re in an MFA program, as you know, there are constant assignments. You have to turn in packets and assignments, and you have to workshop, so that was my process before I had children. When I had children, everything changed—this will sound familiar to many people who are parents—and I only had time in little bursts. That’s when I started writing feverishly and furiously for short amounts of time and then I spend years editing and revising.

JR: This book is more than just poetry, though. It memorializes your family and the grief. You have a line that says, “Obituary writers say that an obit is when a person becomes history…” Did you research a lot of obits when you did this.

VC: I read quite a few obituaries. I thought, “How do people write them?” And they are hilarious. They’re all different. But with obituaries, they’re put together mostly by people who don’t know how to write. The majority of the population didn’t go to school for writing, so obits aren’t a good example of writing. When you think of it, obits are usually written by an unwilling family member who is forced to write it. Because of this, they’re not written very well. I read as many as I could, and I just had to stop reading after a while because of all the clichés.

JR: The book has three parts—the first and third parts are these obituary poems, where you grieve the loss of people and things you lost, including things in the outside world. The inside is a spacious poem, a collection of sonnets in one long poem. Is there a way someone should read OBIT?

VC: I don’t know! One of my former teachers asked me once, “How do you read a book of poetry?” I answered him, “Oh, from the front to the back.” He shook his head and said, “That’s not how I read…” and he started talking about how he read the poetry book all over the place. I actually think people should read it however they want to read it. If they want to read the tankas all at once, that’s great. If they want to read from the first page to the last, if they want to start with that big poem in the middle, if they want to read one poem a day… it’s up to them. I didn’t intend for anyone to read it in any particular order. I think the poems get increasingly outward and external as you go on, but they can read in any order they want.

JR: You even gave Tomas Tranströmer an obit in your book…

VC: Yes! Tranströmer was, I think, a psychologist or a therapist or something, and his images and language are so evocative. Something interests me in his work. So many people have translated his poetry and I’ve read almost every one of the translations, and I’ve compared them really closely, and I really love Tranströmer’s work.

JR: Are you encouraged or influenced by anyone’s work in particular?

VC: I feel like I’ve been influenced by everything I read. I feel like in some ways I don’t have that many distinct influences. I try to make my own path, especially now. When I was young, I learned by reading others, but now I really do try and do my own thing. I trust myself a lot more now.

I love Briget Pegeen Kelly, Larry Levis, Wallace Stevens… I love some of T.S. Eliot, I love Sylvia Plath, and I love a ton of contemporary poets, like Richard Siken, I love Ben Lerner’s books, Danez Smith, Rick Barot, Kaveh Akbar, Tiana Clark, Carolina Ebeid, Eduardo Corral, Carl Phillips, I mean, I could go on forever.

JR: We’re going to have Cassandra López at the next Antioch residency, which makes me so happy because Brother Bullet was one of my favorite books of 2019. It was hypnotic!

VC: Wasn’t that such a good book? I’m so glad you liked it! I liked it, too! I remember first hearing Cassandra reading at the Idyllwild Writers Week and I felt that instantly there’s something special about her work.

JR: I started reading it during the day, and when I looked up, it was dark. It was night. That’s how hypnotic the words on the page were.

VC: The intensity of new poets is amazing. A lot of them are people of color. I think their experience fuels their words on the page. I also think that spoken word poetry influences some of them, too. They understand the urgency and the power of performance. I think they bring all that to the page.

I love to read W.S. Merwin or Sharon Olds or Louise Glück or Jorie Graham—the elder poets, or dead poets are also so important—and then reading the young poets. Having that contrast is everything. I don’t think one is any better than the other, even though they’re different from one another. I love that we can read both, enjoy both, and learn from all of it.

JR: I completely agree. This contrast is so important. I love how you bring all of us together, including some of the poets on this page! Why is it so important to be a good literary citizen today?

VC: We need each other to help see our blind spots, tendencies, and proclivities. Fellow writers can help you see them, and help you learn so that you become better and better. At the very least, you can learn from other people’s mistakes, which helps so much. Otherwise, you’re writing in a vacuum and learning will take twelve times longer. We writers can be solitary and introverted, and we often forget to interact with others. We need to lift each other up.

We also need to be thinking about our larger communities that surround us. I think it’s important to give back to your community and remember where you came from and remember how you felt when you first started.

Janet Rodriguez is an author, teacher, and editor living in Northern California. In the United States, her work has most recently appeared in Eclectica, The Rumpus, Cloud Women’s Quarterly, Salon.com, American River Review, and Calaveras Station. She is the winner of the Bazzanella Literary Award for Short Fiction and the Literary Insight for Work in Translation Award, both from CSU Sacramento in 2017. Currently she is a Cardinal MFA candidate at Antioch University, Los Angeles, where she serves Lunch Ticket as Managing Editor.