Writing: The Toolbox VII

I recently taught a month-long intensive workshop called “Write Your Screenplay in Four Weeks” at St. John’s College in Santa Fe. I’m always struck by how much I learn about writing as I share my own process and watch others develop their own. All my collected rules of writing come into play not only when I sit down and write myself, but also when I teach other writers. From micro to macro, there are patterns of pitfalls and common mistakes, and over time I’ve developed habits to avoid them, which I now like to share with others. Some of the most important of these habits are in learning and applying story structure.

I continue my series writing about the collected tools of the craft, based on my long-standing experience of writing screenplays and books.

19. Using Polarity

I believe the rules that govern electricity also govern our lives in more ways than we may ever be aware of, and yet our language points this out with many words. For instance, the words we use to describe relationships and situations between people are inherently electrical.

“He has magnetism.”

“She is attractive.”

“There’s tension between them.”

“He is a powerful man.”

“She has a certain energy.”

“He was in charge.”

“I was repelled by him.”

We are electrical beings living in an electrical universe. Drama is the applied use of tension. Tension, power, electricity are created by magnetic force of opposing poles. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers by Christopher Vogler, devotes an entire chapter to the use of polarity in storytelling. Conflict, like magnetic energy, is attractive and draws the reader in.

As you conceive of a story, situation, or scene, think in terms of polarity and opposition.

Opposites attract. The man who is afraid of water ends up on the boat. The unemployed man who hates children ends up finding the only job in town teaching kindergarten. The man, who selfishly wants only to win, gives up the chance of winning for a higher purpose. Character polarities create journeys that engage the reader of a book or the audience of a film.

I wrote the movie Glory Road for Disney based on a true story, and in it I created and honed the character of Don Haskins, a man who wanted nothing more than to win. When he gives up the chance to win in the biggest game of his life, because his black players had suffered so much racism that he felt there were more important things than winning, it is the most moving moment in the film. Character journeys follow these paths of reversals, opposition, and polarity. And character journeys—the lessons, the changes—are what make stories compelling.

Polarity and reversals not only make a story satisfying, they follow an almost inevitable path. A man who has hubris and must be taken down. A man who is oppressed must rise and gain his freedom. The poor man who has nothing becomes a rich man. The rich man loses his fortune. The man who takes his life for granted ends up valuing it deeply.

Stories are about change. The greatest change that happens within a character is the move from one opposing side to the other. If you are looking for drama and a satisfying conflict that draws in the reader or audience, think in polarity terms, pull people in opposite directions, and you will create a compelling story.

20. The Three-Act Structure

What is structure? Structure is all around us. Structure is the matrix in which we live. Structure defines us and confines us. The definition of the word structure includes the action of building, arranging things in patterns, plant structures, soil structure, arrangement of particles, economic structures, and personality structures. Structure orders our language, our thinking, our lives. We live inside buildings we call structures where we live structured lives. We may indeed be “trapped” inside structure. It certainly seems that structure is life.

Like the creation story in Hesiod’s Theogony states, as well as the Bible in Genesis: form—(or structure)—came out of the void—out of chaos. Structure is the antithesis to the void and to chaos. Structure is life and creation.

We live in a three dimensional reality, with a fourth dimension being time. This is how life is structured. It’s the physical reality of how things happen on this planet. We move through space on a timeline. This is the nature of stories: the moving of characters through three-dimensional space over time. The structure that helps us navigate this timeline in a story is the three-act structure.

Richard Russo recently spoke at Antioch about his writing process, and he mentioned that he applies a three-act structure to almost everything he writes. The three-act structure is a pattern of beginning, middle, and ending, the key component of any story.

Screenplays are ruled by the three-act structure, and I have come to be so familiar with it, that I automatically order any story I hear into a three-act structure.

Every screenplay begins in Act I with an initial need/problem/task/goal. By page 10 an inciting incident triggers the mechanism for initial change. By page 30, the end of Act I, life changes into a new direction as a result of decisions about how to handle the changing need/problem/task/goal. Act II is all about what happens on the journey to meet the need/problem/task/goal. And it leads to Act III in which a crisis resolves the need/problem/task/goal, and we see that the journey has changed the character in the process.

As mentioned before, that change is often found through applied polarity. At the end of a story, the initial need will have changed, or was never a need, or was answered in a different way. The initial problem was really an opportunity, or never a problem at all, or turns out to be a different problem. The initial task is met, or not met as circumstances have changed. The initial goal is achieved, or not achieved, but now has new meaning.

The three-act structure does not apply in every case of writing, and there are writers who write against convention in order to defy structure. Even then, by the act of writing against convention, they actually validate the convention.

Applying the three-act structure with polarity in the arc of the main character(s) will help you tell your story in a way that appears deeply ingrained in the very fabric of our lives.

21. Story over Situation

I often see that young writers of screenplays will pitch a concept and never make it out of situation, which means they will need to find the story along the way. A situation is a static event, which might include dilemma and conflict, but does not actually go anywhere. A story is a situation with an element thrown in that causes the narrative to propel forward into change.

A strong story will have movement and structure. A situation doesn’t move.

Situation:

A harried man, who always drives everywhere, can’t find his car keys.

Story:

A harried man, who always drives everywhere, can’t find his car keys and is forced to walk across the city, appreciating it for the first time.

Situation:

A young man treats girls badly.

Story:

A young man who treats girls badly wakes up one morning turned into a hot young woman, and has to experience first hand what guys like him are really like.

Situation:

A prejudiced man resentfully lives in a neighborhood in which the presence of foreigners has taken over.

Story:

A prejudiced man resentfully lives in a neighborhood in which the presence of foreigners has taken over, but when he is drawn into the conflicts of his foreign next-door neighbors he begins to bond with them and ends up sacrificing his life to protect them.

Notice not only how stories are agents of change, but how they also move between polarity and opposition, and have three sections, three acts.

I call these components “story logic.” I have come to see story logic everywhere in life. In writing true stories, I have interviewed many people about their lives, and researched so many figures in history, that an astounding pattern becomes evident to me. People’s lives move along predictable story patterns. Psychology, karma, destiny; they all have an algorithm. The ability to understand story structure not only helps me in my writing, it also helps me navigate life. There is something reassuring about that. I always say, “Give me a beginning and I can tell you the ending.” All it takes is an understanding of the rules of change, polarity, and the rhythm of three acts.

Previous posts:

https://lunchticket.org/writing-toolbox/

https://lunchticket.org/writing-toolbox-ii/

https://lunchticket.org/writing-the-toolbox-iii/

https://lunchticket.org/writing-the-toolbox-iv/

https://lunchticket.org/writing-the-toolbox-v/

https://lunchticket.org/writing-the-toolbox-vi/

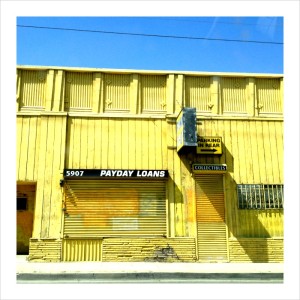

All images courtesy of Bettina Gilois

Bettina Gilois is a Los Angeles based writer whose screen credits include the Bruckheimer film “Glory Road,” for which she was nominated for the Humanitas Prize, as well as “McFarland, USA” starring Kevin Costner, and the HBO movie “Bessie” starring Queen Latifah for which she received an Emmy Nomination for Outstanding Writing. Her book, “Billion Dollar Painter” for Weinstein Books, came out in 2014. She is a special contributor for the Huffington Post in Arts and Culture, and has been a professor of screenwriting at Chapman University, St. John’s College Film Institute in Santa Fe, and now Hofstra University’s Herbert Lawrence School of Communications in NY.