Friends of Friends

Violet and Sydney Schiff were an extremely sophisticated English couple, rich, cultured and cosmopolitan, who moved between London and Paris. He was a translator and writer, using the pseudonym Stephen Hudson, but first and foremost he was a patron of the arts, on friendly terms with Modernism’s greatest talents. She was an elegant and captivating Jewish woman, a friend of Katherine Mansfield and T.S. Eliot. On 18 May 1922, the couple organised an evening that looked likely to go down in history as the dinner party of the era, an event that would bring together the two greatest novelists of the twentieth century: Marcel Proust and James Joyce. The entourage of guests setting the scene for this extraordinary meeting lived up to the occasion: a gala evening in one of the Hotel Majestic’s private rooms, to celebrate the première of Le Renard, the ballet created by Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Diaghilev. As well as the Russian composer and choreographer, other guests included Pablo Picasso, the art critic Clive Bell—Virginia Woolf’s brother-in-law—and the cream of Parisian society. The Schiffs were friends and passionate admirers of Proust. The French writer, whose first four volumes of À la Recherche had already come out, was at the height of his fame: he had won the Prix Goncourt and was published by Gallimard, the most prestigious firm in France. The second volume of Sodom and Gomorrah had appeared a few days before, and in fact Proust had dedicated it to the Schiffs, the soirée’s hosts. The author was very ill: he was abusing a variety of drugs and lived only for his work, shutting himself away to write in his Rue Hamelin apartment and only going out at night after an injection of adrenalin and caffeine to keep him awake. Joyce was the younger by ten years—he had just turned forty—but in Paris, where he had moved as part of his self-imposed exile from Ireland, he was already an idol, the new star of world literature. Ulysses, banned for obscenity in the United Kingdom, had been printed in the French capital just over three months earlier by Shakespeare and Company, the little publisher-bookstore owned by the American Sylvia Beach. Although Joyce was always short of money, he spent freely. He was a heavy drinker and notoriously difficult. Like Proust, he was not in good health: he had iritis as well as heart trouble and was suffering from depression. And like Proust, he thought everything in the world existed only to fill the pages of a book.

Proust arrived shortly afterwards, wrapped in a fur coat, pale and haggard, with the furtive air of a nighthawk or perhaps even a sleek rat, as one of the more malicious guests remembered him.

Those who were friends with both writers were convinced that the meeting between them would be perfect. They had imagined it for a long time and now the moment had finally arrived. Like all self-respecting stars, both guests of honour arrived seriously late, after midnight. Joyce was the first to turn up, already drunk and not wearing evening dress. As soon as he was seated, the Irish writer set to drinking an inordinate amount of champagne, perhaps partly to hide his awkwardness and his dislike of the moneyed, mondaine environment. He sank into his usual silence, occasionally snorting or dozing off. Proust arrived shortly afterwards, wrapped in a fur coat, pale and haggard, with the furtive air of a nighthawk or perhaps even a sleek rat, as one of the more malicious guests remembered him. The Schiffs welcomed him with all honours and gave him a seat next to Joyce, as planned. Everyone thought that the meeting between the two geniuses would lead to urbane and cultivated discussions, unmissable exchanges of ideas and opinions, perhaps disputatious scuffles and skirmishes, and certainly enough material to feed the Parisian gossip columns for who knows how long. But it didn’t turn out at all as expected.

To break the ice, Proust asked Joyce if he knew the Duke of so-and-so, and Joyce replied tersely that he didn’t. Then he asked him if he liked truffles, and Joyce replied that he did. After that the conversation petered out. Violet Schiff, hoping to fire it up again, asked Proust if he had read Ulysses and Proust said “No, I regret I don’t know Mr. Joyce’s work.” And Joyce immediately countered with: “I have never read Monsieur Proust.” In the end, they both started complaining of their ailments: Joyce was tormented by migraines and a burning sensation in his eyes, while Proust grumbled about his stomach ache. “I really must leave,” said the French writer at last. “I’d go too,” replied Joyce, “if I could just find someone to prop me up.”

This is, more or less, all there is to say about the meeting. A meeting that soon became legend, but which culminated in an exchange of wretched remarks about truffles and stomach ache.

* * *

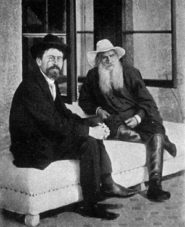

There are two photographs showing Anton Chekhov and Leo Tolstoy together at Gaspra, where the author of War and Peace had moved in 1901, to recuperate from a succession of illnesses in the warm sun of Crimea. Chekhov, who lived nearby in Yalta, heard Tolstoy was there and went to visit him, even though his own state of health was very precarious. Chekhov always became anxious before a meeting with Tolstoy: in his insecurity, he would try on different clothes and spend a lot of time getting ready. You can see it in the photographs: one of them shows the two writers sitting side-by-side on a white divan on the terrace, and Chekhov’s submissive deference towards the great old man is immediately obvious from their different poses. Chekhov is dressed in a dark suit and matching hat, a white shirt and tie and a pince-nez. Sitting hunched, with his legs tightly crossed and his hands clasped around his knee, he looks as though he wants to take up the least space possible. Tolstoy, on the other hand, looks very relaxed: wearing a loose cloak, long riding boots and a wide-brimmed white hat, he is leaning back on his elbow, one leg curled up under his other thigh. In the other photograph, Tolstoy is sitting at a little table, on the same terrace. They’re taking tea together, but Chekhov’s posture is, if anything, even more rigid and subservient: sitting some way from the table, he doesn’t meet Tolstoy’s eyes, but sits with his head bowed, his legs once again crossed and his hands folded in his lap. He appears almost contrite.

There are two photographs showing Anton Chekhov and Leo Tolstoy together at Gaspra, where the author of War and Peace had moved in 1901, to recuperate from a succession of illnesses in the warm sun of Crimea. Chekhov, who lived nearby in Yalta, heard Tolstoy was there and went to visit him, even though his own state of health was very precarious. Chekhov always became anxious before a meeting with Tolstoy: in his insecurity, he would try on different clothes and spend a lot of time getting ready. You can see it in the photographs: one of them shows the two writers sitting side-by-side on a white divan on the terrace, and Chekhov’s submissive deference towards the great old man is immediately obvious from their different poses. Chekhov is dressed in a dark suit and matching hat, a white shirt and tie and a pince-nez. Sitting hunched, with his legs tightly crossed and his hands clasped around his knee, he looks as though he wants to take up the least space possible. Tolstoy, on the other hand, looks very relaxed: wearing a loose cloak, long riding boots and a wide-brimmed white hat, he is leaning back on his elbow, one leg curled up under his other thigh. In the other photograph, Tolstoy is sitting at a little table, on the same terrace. They’re taking tea together, but Chekhov’s posture is, if anything, even more rigid and subservient: sitting some way from the table, he doesn’t meet Tolstoy’s eyes, but sits with his head bowed, his legs once again crossed and his hands folded in his lap. He appears almost contrite.

During this meeting, Tolstoy spoke a good deal, as usual, addressing a wide range of subjects. When the moment came for them to part he asked his friend to give him a farewell kiss. As Chekhov leaned forwards to embrace him, Tolstoy whispered earnestly in his ear: “You know, I hate your plays. Shakespeare was a terrible writer, but your plays are worse than his.”

During this meeting, Tolstoy spoke a good deal, as usual, addressing a wide range of subjects. When the moment came for them to part he asked his friend to give him a farewell kiss. As Chekhov leaned forwards to embrace him, Tolstoy whispered earnestly in his ear: “You know, I hate your plays. Shakespeare was a terrible writer, but your plays are worse than his.”

Knowing Tolstoy and his idiosyncrasies, Chekhov can’t have been all that surprised. In any event, it wasn’t the first time that the ageing writer had criticised his plays. Once before he’d said: “A playwright should lead the spectator by the hand and take him where he wants him to go. And to where can I follow your characters? To the sofa in the drawing room and back again, because they’ve got nowhere else to go.” They laughed together about this, but Tolstoy had inadvertently put his finger on the originality of Chekhov’s dramatic concept, which would revolutionise twentieth-century theatre. Yet he continued to regard the lack of action in such plays as an unforgivable defect. Chekhov, on the other hand, worshipped Tolstoy like a god. On 11 December 1891, he wrote in a letter to his publisher, Alexei Suvorin: “Oh, Tolstoy, Tolstoy! These days he’s no longer a man but a superman, a Jupiter.” His adoration was such that he even derived some form of pleasure from being disparaged by his god. Actually, what he admired most about Tolstoy was the regal contempt he showed towards all writers. And even though sometimes Tolstoy admitted to appreciating Chekhov’s skill as a writer of short stories, describing him as “an incomparable artist”, technically superior to anyone else, the younger writer could never bring himself to believe that his work really pleased him: “It might seem that from time to time he praises Maupassant, or Kuprin, or Semenov, or even myself, but why does he praise us? It’s simple: because he sees us as children. And indeed, compared with his work, our stories and novels are all just children’s games.”

There was much that was Oedipal in Chekhov’s ambivalent attitude towards the grand old man of Russian literature.

Yet before he got to know Tolstoy, Chekhov had published an anonymous article in the newspaper New Times in which he attacked the writer for his condemnation of modern society. And in a later letter to his publisher he literally damned to hell “the philosophy of the great men of this world”, with particular reference to Tolstoy. There was much that was Oedipal in Chekhov’s ambivalent attitude towards the grand old man of Russian literature. One moment he was being hostile towards him, the next he was lavishing extravagant praise on him. The truth is that since a very young age, meeting Tolstoy had been not only Chekhov’s greatest desire, but also a source of terror. (Incidentally Tchaikovsky also admitted, years later, that he had felt “an incredible sense of panic” before meeting Tolstoy, who apparently frightened the life out of everyone.) When at last mutual friends succeeded in persuading Chekhov to go to Yasnaya Polyana, their first encounter took place in almost surreal circumstances. It was 8 May 1895 and Chekhov arrived at the very moment when the count was about to go and bathe in the river Upa, as he did every morning. As soon as he saw him, Tolstoy invited his new visitor to join him. Chekhov didn’t dare refuse and was obliged to undress in front of his Jupiter, whose long white beard bobbed majestically in front of him while they sat naked together in the water.

The meeting was far from disappointing. Tolstoy, in a letter to his son a few months later, described Chekhov as a gifted man with a kind heart. From then on, he remained friendly towards him, charmed by his humanity, his reserve, his calm manner and his “girlish” walk. Chekhov too came away from that first encounter with a “wonderful impression”. He described in a letter how he had felt at ease, as though in his own home, and had conversed freely with Lev Nikolayevich. I don’t know how truthful he was being. Looking at the Crimea photographs, it’s hard to imagine Chekhov feeling at ease while bathing naked with Tolstoy in the river. In fact, I can’t believe he ever really felt at ease with him, because he was cowed by him until the very end. And he certainly can’t have felt comfortable the next time they met, two years later, when Tolstoy went to visit him in a Moscow hospital. Chekhov had been taken there as an emergency after his first serious pulmonary haemorrhage, which had happened over dinner in a restaurant. Diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis, he was confined to bed and a regime of silence for several days. Only his closest relatives were allowed to visit him and then only for a short time. But when Tolstoy arrived, wrapped in his enormous bearskin coat, no one had the courage to turn him away. He sat down beside Chekhov’s bed and talked to him at length about the immortality of the soul. “All of us,” he said, “animals as well as men, will continue to live on in some principle (reason or love), the essence and purpose of which are a mystery to us.” But to Chekhov the principle described by Tolstoy seemed a “shapeless gelatinous mass” rather than a mystery. However, sentenced to silence, he was unable to explain himself better, though he later remarked in a letter to a friend: “I have no use for such immortality, I don’t understand it, and Lev Nikolayevich was surprised that I didn’t understand.”

* * *

As a boy, convalescing after a long illness, I happened to read a story by Henry James called “The Friends of the Friends,” which recounts the repeated and vain attempts by the narrator to introduce a male and a female friend to each other. These two had in common a private supernatural experience that had marked both their lives: the sudden, very vivid but fleeting apparition of a parent—her father and his mother—at the exact moment of their deaths, though both had died far from where the apparitions occurred. For years, despite the most favourable circumstances for a perfect meeting, every plan to bring them together comes to nothing, foiled by a series of hitches, misunderstandings and unexpected events. But at last the death of one the two—the woman, who had heart disease—achieves what had never proved possible in life. That very evening, the man is at last brought face-to-face with the dead “friend of his friend,” who comes to him in an ephemeral but telling apparition: they both gaze at each other silently for twenty minutes or so, in a prelude to becoming definitively united around six years later when the man dies, giving in to a “long necessity,” as though answering “an irresistible call.”

Deep down, we have a fear of bonding, of fusing with someone else. Perhaps that’s also why, in ordinary life, so many meetings that ought to be perfect are doomed to founder.

For a long time, I was obsessed by this story. Perhaps it was partly as a result of the illness I associated with it (like Mahler’s Fifth, which I heard for the first time during that same convalescence: since then I’ve always felt there’s something slightly febrile about its splendid opening and that trumpet fanfare in C sharp minor). I used to encourage everyone to read it and I even tried to get a screenplay and a reworking of the narrative out of it. I wrote a story called “Friends,” whose protagonist was a broker of elective affinities, a master of matchmaking, a man who had spent most of his life engineering perfect meetings between friends in common, manipulating destinies from the shadows, with a particular flair for weaving invisible webs of allusions, associations, and flattery. I even came up with a surprise ending that shifted into the supernatural, just like the Henry James story, but then I threw the whole thing away, concluding that the task was beyond my capabilities. Yet I still couldn’t stop brooding on the story: I kept wondering what the author was trying to tell us in this brief tale, so subtle that it verges on the abstract. A man and a woman who seem to be made for each other, but who never manage to meet except as ghosts. Perhaps he was trying to tell us that two human beings can never really meet? That you can only truly connect with someone else in absentia? That we must all surrender to the solitude of the soul? I don’t like to sound so pessimistic, but surely, we have all felt such a sweeping awareness at least once in our life. Perhaps this is what I was feeling in those years when the story obsessed me. After all, there’s no doubt as to what James was doing with the traditional ghost-story format: his ghosts are always and only phantoms of the mind, projections of the unconscious. Impossibilities, obstacles, hindrances—they’re all mostly within us, affecting our readiness to accept others, to receive them as though they were a part of us, even though we feel so similar, such kindred spirits, or perhaps precisely because of that. Deep down, we have a fear of bonding, of fusing with someone else. Perhaps that’s also why, in ordinary life, so many meetings that ought to be perfect are doomed to founder. Something always goes wrong: crossed wires, an indisposition, a misunderstanding, an act of reciprocal sabotage.

* * *

One of the most interesting aspects of the meetings between Chekhov and Tolstoy is that communication between them was almost always indirect, in letters or diary entries, and especially through other people. They met rarely and almost always in the presence of others: Tolstoy’s children and relatives or “friends of friends,” who then also expressed their opinions in diaries and letters about the meetings and about the relationship between the two writers. But did they ever truly meet? Unlike Proust and Joyce, they saw each other more than once and they didn’t talk about truffles or stomach aches, but exactly what we might expect two such giants of literature to discuss together: life, books, the immortality of the soul. Yet incomprehension pervaded their meetings. They were friends, they liked each other, but they didn’t understand each other because they were so different. Chekhov’s modesty before Tolstoy was almost embarrassing when you think how great a writer he was, while Tolstoy probably believed even more strongly than his friend that he was an immortal god. Tolstoy couldn’t bear doctors and preached a new gospel, while Chekhov, a doctor and an atheist, had no inclination for Tolstoyism—although he flirted with it for a few years—and in general didn’t lean towards any “clearly defined political, religious or philosophical point of view.” One was a count, son of a princess of ancient lineage, who idealised the peasant world and dreamt of becoming poor; the other was the son of a small shopkeeper, descended from a family who had once been serfs, a man who had known poverty and abuse as a child and believed in progress. Their paths led in opposite directions. I’m not sure that they really had anything in common, except for the fact that they both put the human condition at the centre of their work. Perhaps, without wanting to admit it, they felt threatened by each other. Tolstoy thought Chekhov as a man was “simply wonderful,” but perhaps thought less of him as an artist. In his diaries, he compared Chekhov’s importance as a writer to Pushkin, but the compliment only went so far. As with Pushkin, he deplored the “lack of content” in his friend’s work. Chekhov, for his part, never relinquished his Oedipal attitude towards Tolstoy. He never forgave the conservatism of his artistic judgements nor did he share his moral condemnation of modern society. And yet he thought him the greatest of all. Once he confessed that he had “never loved anyone as much as him.”

* * *

Some time after the disastrous dinner at the Hotel Majestic, James Joyce said he regretted the missed opportunity, even though his relationship with Proust remained ambivalent. He put it about that he had never had the time to read Proust’s work, and missed no opportunity to express opinions that were lukewarm, or indifferent, or downright negative about “a certain Mr Marcel Proust of here,” as he wrote dismissively to his friend Frank Budgen shortly after arriving in Paris, when the intellectual milieu of the capital was apparently seeking to match him against his rival. On one occasion he described Proust’s writing as “analytic still life.” The fame of À la Recherche probably nettled him, but he was even more irked by the fact that its author could write in “a comfortable place at the Étoile, floored with cork and with cork on the walls to keep it quiet,” while he had to write Ulysses in an apartment that was so noisy he might as well have been working in the street.

But when Proust died, on 18 November 1922, six months after the meeting at the Majestic, Joyce went to his funeral. Perhaps, like the character in the story by Henry James, he too felt a “long necessity,” an “irresistible call.” The same call that a month earlier had prompted him to write to his publisher/bookseller, with something between irreverent wit and belated tribute, that he had read the first two volumes recommended by Mr. Schiff of “À la Recherche des Ombrelles Perdues par Plusieurs Jeunes Filles en Fleurs du Côté chez Swann et Gomorrhée et Co. par Marcelle Proyce et James Joust.”

As though in that cryptic reference to an imaginary parody of À la Recherche written by four hands, whose authors’ names were welded together from their own two names, Joyce and Proust had finally got to meet through the acrobatics of language, redressing the famous failure of their meeting on 18 May 1922.

![]()

Gli amici degli amici

Violet e Sidney Schiff erano una mondanissima coppia di ricchi, colti e cosmopoliti inglesi che viveva tra Londra e Parigi. Lui era un traduttore e uno scrittore che usava lo pseudonimo di Stephen Hudson, ma era soprattutto un mecenate che conosceva i più grandi artisti e talenti del modernismo. Lei era un’elegante e affascinante signora ebrea, amica di Katherine Mansfield e T.S Eliot. Il 18 maggio 1922 i due organizzarono quella che doveva restare nella memoria storica come la cena del secolo, una serata dove far incontrare i due più grandi romanzieri del Novecento: Marcel Proust e James Joyce. Il parterre di ospiti che avrebbe fatto da corteo all’eccezionale incontro era consono all’evento: l’occasione era una serata di gala da dare in una sala riservata dell’Hotel Majestic per festeggiare la prima di Le Renard, il balletto di Igor Stravinskij e Sergej Djagilev. Oltre al musicista e al coreografo russi, erano stati invitati anche Pablo Picasso, il critico d’arte Clive Bell, cognato di Virginia Woolf, e la crema della nobiltà parigina. Gli Schiff erano amici e ammiratori fanatici di Proust. Lo scrittore francese, con i suoi primi quattro volumi della Recherche già pubblicati, era all’apice della sua gloria, aveva vinto il premio Goncourt ed era stampato da Gallimard, l’editore più prestigioso di Francia. Pochi giorni prima era uscito il secondo tomo di Sodoma e Gomorra, che l’autore aveva dedicato proprio agli Schiff, gli anfitrioni della serata. Proust era molto malato, faceva abuso di svariate droghe e viveva per la sua opera: si era autorecluso per scrivere nel suo appartamento di rue Hamelin e usciva solo di notte, dopo un’iniezione di adrenalina e caffeina, che gli permetteva di restare sveglio. Joyce era più giovane di dieci anni—ne aveva appena compiuti quaranta—ma nell’ambiente parigino era già un idolo, il nuovo astro della letteratura mondiale. Censurato per oscenità nel Regno Unito, il suo Ulisse era stato pubblicato poco più di tre mesi prima con una piccola casa editrice-libreria, la Shakespeare and Company della statunitense Sylvia Beach, proprio nella capitale francese, dove Joyce si era trasferito scegliendo l’esilio volontario dall’Irlanda. Seppure sempre a corto di denaro, lo scrittore spendeva senza ritegno, era un forte bevitore e aveva un carattere notoriamente difficile. Anche lui, come Proust, non stava bene in salute: aveva problemi di cuore e di irite, e soffriva di depressione; e anche lui, come Proust, pensava che tutto al mondo esistesse per far capo a un libro.

Gli amici in comune giuravano che l’incontro tra i due sarebbe stato perfetto. Lo sognavano da tempo e ora l’occasione era finalmente arrivata. Entrambi gli ospiti d’onore, come ogni star che si rispetti, arrivarono con notevole ritardo, dopo la mezzanotte. Prima Joyce, che si presentò già ubriaco e sprovvisto di abito da cerimonia. Lo scrittore irlandese, appena seduto a tavola, continuò a bere champagne in modo esagerato, forse anche per nascondere il proprio disagio e l’insofferenza per l’ambiente troppo ricco e mondano. Si chiuse nel suo abituale silenzio e ogni tanto sbuffava o sonnecchiava. Poco dopo arrivò Proust, che apparve avvolto in una pelliccia, pallido e smunto, con l’aria furtiva di un rapace notturno o perfino, come sembrò a qualcuno dei presenti più malevoli, di un “viscido topo”. Gli Schiff lo accolsero con tutti gli onori e lo fecero sedere accanto a Joyce, come previsto. L’incontro tra i due geni dal quale tutti si aspettavano dovessero scaturire dialoghi colti e raffinati, imperdibili scambi di idee e di punti di vista, magari scontri dialettici e divergenze, e in ogni modo materiale sufficiente ad alimentare le cronache mondane parigine per chissà quanto tempo, andò in maniera del tutto inaspettata.

Proust, per rompere il ghiaccio, chiese a Joyce se conoscesse un certo duca, e Joyce rispose di secco di no. Poi gli domandò se gli piacessero i tartufi e Joyce rispose di sì. A quel punto la conversazione languì. Violet Schiff, nella speranza di rianimarla, chiese a Proust se avesse letto l’Ulisse e Proust disse: “No, mi dispiace, non conosco l’opera di mister Joyce”. E Joyce, di rimando, contraccambiò: “Neanche io ho mai letto monsieur Proust”. Infine entrambi si lamentarono dei loro malanni: Joyce dell’emicrania che lo stava tormentando e del bruciore agli occhi, Proust del suo mal di stomaco. “Devo proprio andare” disse, alla fine, lo scrittore francese. “Lo farei anche io—rispose Joyce—se solo trovassi qualcuno che mi sorregga”.

Questo, più o meno, il resoconto dell’incontro fra i due. Un incontro che divenne presto leggenda, ma che si concluse con un misero scambio di battute sui tartufi e sul mal di stomaco.

* * *

Due foto ritraggono insieme Anton Čechov e Lev Tolstoj, a Gaspra, dove l’autore di Guerra e pace si era trasferito nel 1901 per riprendersi da una serie di malanni al caldo sole della Crimea. Čechov, che viveva nella vicina Yalta, quando lo venne a sapere lo andò a trovare, benché anche le sue condizioni di salute fossero molto precarie. Prima di un incontro con Tolstoj, Čechov entrava sempre in ansia: si provava diversi vestiti ed era insicuro, perdendo molto tempo nei preparativi. Lo si capisce anche guardando le foto: in una i due scrittori sono seduti insieme su un divano bianco senza schienale, in terrazza, e dalle pose diverse si nota subito la deferenza e la soggezione di Čechov nei confronti del grande vecchio. In abito scuro, camicia bianca e cravatta, cappello intonato al vestito e pince nez, se ne sta curvo, con le gambe rigidamente accavallate e le mani intrecciate al ginocchio, quasi come se volesse occupare il minor spazio possibile. Tolstoj, invece, appare molto disinvolto: indossa un’ampia mantella, stivaloni da cavallerizzo e un cappello bianco a falde larghe, con una gamba piegata sotto la coscia e il gomito appoggiato al bordo del divano. Nell’altra foto Tolstoj è seduto a un tavolino, sulla stessa terrazza: i due stanno prendendo il tè insieme, ma qui l’atteggiamento di Čechov è, se possibile, ancora più rigido e remissivo: siede distante dal tavolo e non regge lo sguardo di Tolstoj, ma tiene la testa abbassata, le gambe ancora accavallate e le mani conserte in grembo, con un atteggiamento quasi contrito. Durante quell’incontro Tolstoj, come di consueto, parlò molto, affrontando vari argomenti, e quando si avvicinò il momento del congedo chiese all’amico di dargli un bacio di addio. Mentre Čechov si chinò su di lui per salutarlo, Tolstoj gli sussurrò all’orecchio, con tono energico: “Tu lo sai, io odio i tuoi drammi. Shakespeare era un pessimo scrittore, ma i tuoi drammi sono peggiori dei suoi”.

Conoscendo Tolstoj e le sue idiosincrasie, Čechov non deve essersi stupito più di tanto. Del resto, non era la prima volta che il vecchio scrittore criticava il suo teatro. Una volta gli disse: “Un drammaturgo dovrebbe prendere uno spettatore per mano e condurlo dove lui vuole. E dove posso seguire i tuoi personaggi? Dal divano al soggiorno e ritorno, perché non hanno altro luogo dove andare”. Ne risero insieme, ma senza volerlo Tolstoj aveva colto in pieno la novità del teatro di Čechov, la sua concezione drammaturgica che avrebbe rivoluzionato la scena del Novecento. Eppure si ostinava a considerare la mancanza di azione di quei drammi come un difetto imperdonabile. Čechov, da parte sua, venerava Tolstoj come un dio. In una lettera al suo editore, Aleksej Suvorin, l’11 dicembre 1891, scriveva: “Oh, quel Tolstoj, quel Tolstoj! Egli, oggi, non è un essere umano, ma un superuomo, uno Zeus”. La sua adorazione arrivava al punto che perfino nell’essere denigrato dal suo dio trovava una forma di piacere. Ciò che ammirava di più in Tolstoj, infatti, era proprio questa regale forma di disprezzo che nutriva nei confronti di tutti gli scrittori. E anche se a volte Tolstoj non gli nascose la sua ammirazione come autore di novelle, definendolo “un artista incomparabile”, tecnicamente superiore a chiunque altro, Čechov non osò mai credere di piacergli davvero: “Si può pensare che, di tanto in tanto, egli elogi Maupassant, o Kuprin, o Semënov, o me stesso—disse—ma perché ci elogia? È semplice: perché ci considera come dei bambini. I nostri racconti, i nostri romanzi, in confronto ai suoi lavori, sono infatti tutti dei giochi da bambini”.

Eppure, prima di conoscere Tolstoj, Čechov aveva pubblicato un articolo anonimo sulla rivista “Il Tempo Nuovo” dove attaccava lo scrittore per la sua condanna della società moderna. E in una lettera successiva al suo editore, aveva mandato letteralmente al diavolo “la filosofia dei grandi di questo mondo”, includendovi soprattutto Tolstoj. C’era molto di edipico in questo atteggiamento ambivalente che Čechov mostrava nei confronti del vecchio padre della letteratura russa. La sua ostilità verso l’uomo si alternava alle sperticate lodi che elargiva all’artista. In realtà incontrarlo era stato, fin da giovanissimo, il suo più grande desiderio, ma ne era anche terrorizzato (e del resto, anche Čajkovskij confesserà, anni dopo, di aver provato un “incredibile senso di panico” prima del suo incontro con Tolstoj, che a quanto pare metteva paura a tutti). Quando finalmente gli amici in comune riuscirono a convincere Čechov a recarsi a Jasnaja Poljana, il primo incontro avvenne in una situazione quasi surreale. Era l’8 maggio 1895 e Čechov si presentò proprio nel momento in cui il conte stava andando a farsi il bagno, come ogni mattina, nelle acque del fiume Upa. Vedendolo, Tolstoj invitò il nuovo arrivato a unirsi a lui. Čechov non osò contraddirlo e fu costretto a spogliarsi davanti al suo Zeus, la cui lunga barba bianca, mentre se ne stavano entrambi nudi nell’acqua, galleggiò solennemente per tutto il tempo davanti a lui.

L’incontro fu tutt’altro che deludente. Tolstoj, in una lettera al figlio qualche mese dopo, definì Čechov un uomo “pieno di talento” e dal “cuore buonissimo”, e da allora non smise mai di volergli bene. Era incantato dalla sua umanità, dalla sua riservatezza, dai suoi modi tranquilli e dalla sua “andatura da signorina”. Anche Čechov ricavò da quel primo incontro un’“impressione meravigliosa”. Confessò, in una lettera, di essersi sentito a suo agio, come se fosse stato a casa sua, e di aver conversato liberamente con Lev Nikolaevič. Non so fino a che punto fossero sincere queste parole. Mi sembra difficile, vedendo le foto della Crimea, immaginare Čechov a suo agio con Tolstoj mentre facevano il bagno nudi nel fiume. Credo invece che a suo agio con lui non lo sia mai stato, perché continuò ad averne soggezione fino alla fine. E di sicuro non lo fu nel successivo incontro, due anni dopo, quando Tolstoj lo andò a trovare in clinica a Mosca, dove Čechov era stato ricoverato d’urgenza dopo la sua prima grave emorragia polmonare, avuta durante una cena in un ristorante. Gli diagnosticarono una tubercolosi avanzata e per vari giorni fu costretto al letto e al silenzio. Solo i parenti più stretti erano autorizzati a fargli visita e per poco tempo. Ma quando si presentò Tolstoj, avvolto nella sua enorme pelliccia d’orso, nessuno ebbe il coraggio di mandarlo via. Si sedette accanto al letto di Čechov e gli parlò a lungo dell’immortalità dell’anima. “Tutti noi, uomini e animali—disse—vivremo in un principio (ragione, amore), l’essenza e il fine del quale costituisce per noi un mistero”. Più che un mistero, però, a Čechov questo principio di cui parlava Tolstoj pareva una “informe massa gelatinosa”. Ma, ridotto al silenzio, non riuscì a spiegarsi meglio, salvo poi commentare in una lettera a un amico: “D’una simile immortalità non so che farmene, non lo capisco, e Lev Nikolaevič era sorpreso ch’io non capissi”.

* * *

Da ragazzo, durante la convalescenza da una lunga malattia, mi capitò di leggere un racconto di Henry James, intitolato Gli amici degli amici, che descrive i ripetuti e vani tentativi da parte della narratrice di far incontrare il suo fidanzato e un’amica uniti da una segreta esperienza soprannaturale che aveva segnato il loro passato: l’apparizione, vividissima e improvvisa, ma subito svanita, di un genitore—il padre di lei e la madre di lui—nell’attimo stesso in cui moriva, in realtà molto lontano dal luogo di quell’apparizione. Nonostante le migliori premesse per l’incontro perfetto, per anni si riveleranno inutili tutti gli appuntamenti organizzati, puntualmente falliti a causa di continui imprevisti, malintesi e ostacoli. Finché la morte di uno dei due—la donna, malata di cuore—renderà possibile ciò che in vita non era mai avvenuto. L’uomo, infatti, quella sera stessa finalmente incontra la defunta “amica dell’amica” in un’apparizione fugace ma rivelatrice: i due si guardano in silenzio per una ventina di minuti, preludio a quell’unione definitiva che avverrà dopo cerca sei anni, quando anche l’uomo cesserà di vivere, cedendo a una “prolungata necessità”, come se avesse risposto a un “irresistibile richiamo”.

Per molto tempo sono stato ossessionato da questo racconto. Parte di questa ossessione era dovuta forse alla malattia a cui lo avevo associato (come la Quinta di Mahler che ascoltai per la prima volta durante quella stessa convalescenza, il cui splendido attacco, con la fanfara della tromba in si bemolle, ha conservato per me da allora sempre un che di febbrile). Consigliavo di leggerlo a chiunque e provai perfino a ricavarne una sceneggiatura e una rielaborazione narrativa. Scrissi un racconto intitolato Amici, che aveva come protagonista un sensale delle affinità elettive, un artista degli appuntamenti concertati, un uomo che aveva impiegato la maggior parte della sua vita a organizzare incontri perfetti fra amici comuni, a manovrare destini rimanendo nell’ombra, con una capacità particolare nel tessere una rete invisibile di allusioni, riferimenti, lusinghe. E mi inventai pure un finale a sorpresa, che sfociava nel soprannaturale, proprio come il racconto di James, ma poi buttai tutto, considerando il compito al di sopra delle mie capacità. Eppure non smisi di rimuginare su quel racconto: continuavo a chiedermi che cosa avesse voluto raccontarci l’autore con questa novella di una sottigliezza che rasenta l’astrazione. Un uomo e una donna che sembrano fatti l’uno per l’altra, ma che non riusciranno mai a incontrarsi, se non come fantasmi. Forse voleva dirci che nessun incontro reale è mai possibile tra due esseri umani? Che solo in absentia si può entrare davvero in contatto con qualcuno? Che siamo, noi tutti, votati alla solitudine dell’anima? Non vorrei essere così pessimista, ma certo ciascuno di noi, almeno una volta nella vita, deve aver provato una consapevolezza così radicale. E forse devo averla provata anche io negli anni della mia ossessione per questo racconto. Del resto, è noto quale uso James ha saputo fare della tradizione anglosassone del ghost-novel: i suoi fantasmi sono sempre e solo fantasmi della mente, proiezioni dell’inconscio. L’impossibilità, l’ostacolo, l’impedimento, sono dunque soprattutto dentro di noi, nell’idea di poter accettare qualcuno, accoglierlo come parte di noi stessi, benché lo si senta così simile, così affine, o forse proprio per questo. È, in fondo, la paura di amalgamarsi, di fondersi con l’altro da sé. Forse è anche questo il motivo per cui molto spesso nella vita ordinaria gli incontri che si prefigurano perfetti sono destinati a naufragare. C’è sempre qualcosa che non funziona: un equivoco, un’indisposizione, un misunderstanding, un atto di reciproco sabotaggio.

* * *

Uno degli aspetti più interessanti degli incontri tra Čechov e Tolstoj è che i due hanno comunicato quasi sempre indirettamente, in lettere o pagine di diario, e soprattutto attraverso altre persone. I loro incontri furono pochi e avvennero quasi sempre in presenza di testimoni: figli e parenti di Tolstoj o “amici degli amici”, che a loro volta hanno raccontato in diari e lettere il loro punto di vista su questi incontri e sul rapporto tra i due scrittori. Ma s’incontrarono mai realmente? A differenza di Proust e Joyce, si videro più di una volta, e non parlarono di tartufi o mal di stomaco, ma proprio di ciò di cui ci aspetteremo che parlino due giganti della letteratura come loro quando si incontrano: la vita, i libri, l’immortalità dell’anima. Eppure gli incontri tra id due furono pieni di incomprensioni. Erano amici e si volevano bene, ma non si capivano, perché troppo diversi. Čechov nei confronti di Tolstoj era di una modestia quasi imbarazzante se si pensa alla sua grandezza di scrittore, mentre Tolstoj con molta probabilità era convinto anche più dell’amico di essere un dio immortale. Tolstoj odiava i medici e predicava un nuovo vangelo, mentre Čechov, che era medico e ateo, non aveva nessuna predisposizione per il tolstoismo—nonostante un’iniziale infatuazione durata qualche anno—e in generale non ne aveva per nessun “punto di vista politico, religioso e filosofico ben definito”. L’uno era un conte, figlio di una principessa d’antica stirpe, idealizzava il mondo contadino e sognava di diventare povero; l’altro, figlio di un piccolo bottegaio, discendeva da una famiglia di ex servi della gleba, aveva conosciuto miseria e maltrattamenti da bambino, e credevo nel progresso. Le loro strade seguivano sentieri opposti. Non sono sicuro che avessero davvero qualcosa in comune, salvo il fatto di aver entrambi posto al centro della loro opera l’uomo. Forse, senza volerlo ammettere, si sentivano minacciati l’uno dall’altro. Tolstoj considerava l’uomo Čechov “semplicemente meraviglioso”, forse superiore all’artista. Nei suoi diari paragonò la sua importanza di scrittore a quella di Puškin, ma era un complimento fino a un certo punto. Come in Puškin, condannava infatti nell’opera dell’amico la “mancanza di contenuto”. Čechov, da parte sua, non smise mai il suo atteggiamento edipico nei confronti di Tolstoj. Non gli perdonava il suo conservatorismo nei giudizi artistici e non condivideva la sua condanna morale della società moderna. Eppure lo considerava il più grande di tutti. Una volta confessò di non aver “mai amato nessuno come lui.”

* * *

Qualche tempo dopo la disastrosa cena all’Hotel Majestic, James Joyce espresse rammarico per quell’occasione mancata, anche se il suo rapporto con Proust fu sempre ambivalente. Andava dicendo di non aver mai avuto il tempo di leggere la sua opera, e non mancava occasione per dispensare apprezzamenti tiepidi o indifferenti o decisamente negativi sul suo collega rivale, quel “certo Marcel Proust di qui”—come scrisse sprezzante al suo amico Frank Budgen poco dopo essere approdato a Parigi—che l’ambiente intellettuale della capitale pareva volesse mettere contro di lui. Una volta definì la scrittura proustiana una “natura morta analitica”. La fama della Recherche, probabilmente, lo infastidiva, ma ancor di più lo infastidiva il fatto che il suo autore potesse scrivere in “un posto comodo all’Étoile, col pavimento e le pareti imbottite di sughero perché nulli turbi la sua tranquillità”, mentre lui era stato costretto a scrivere il suo Ulisse in un appartamento così rumoroso che era come trovarsi per strada.

Eppure, quando Proust morì, il 18 novembre 1922, sei mesi dopo l’incontro al Majestic, Joyce andò al suo funerale. Forse anche lui, come il personaggio del racconto di Henry James, cedendo a una “prolungata necessità”, a un “richiamo irresistibile”. Quello stesso richiamo che appena un mese prima gli aveva fatto scrivere in una lettera alla sua editrice-libraia, tra l’arguzia irriverente e l’omaggio postumo, di aver letto i primi due volumi consigliatigli da Mr Schiff della “Recherche des Ombrelles Perdues par Plusieurs Jeunes Filles en Fleurs du Côté de chez Swann et Gomorrhée et Co. par Marcelle Proyce and James Joust”.

Come se in quel criptico riferimento a una immaginaria parodia della Recherche scritta a quattro mani, coi nomi degli autori composti dalla fusione dei loro due nomi, Joyce e Proust avessero finalmente realizzato, attraverso le funambolerie del linguaggio, quel famoso incontro mancato del 18 maggio 1922.

Translator’s Note:

“Friends of Friends” (Gli Amici degli Amici) is an extract from Fabrizio Coscia’s book Soli Eravamo (“We Were Alone”), originally published in Italian by Ad Est dell’Equatore in 2015. Soli Eravamo is a collection of twenty-one essays/stories which examine moments in the lives of some of the great figures of Western art, literature, and music, including Kafka, Joyce, Proust, Dante, Hopper, Vermeer, Caravaggio, Mozart—and Radiohead. Coscia probes the humanity of these luminaries, making connections between them and creating surprising juxtapositions, drawing the threads together with his own personal reflections on life, art, and the relationship between the two.

In “Friends of Friends,” Coscia explores the disastrous meeting between Marcel Proust and James Joyce, the unequal relationship between Chekhov and Tolstoy, and Henry James’ story about a woman’s failed attempt to introduce two mutual friends. Each of these episodes is fascinating in its own right, but Coscia finds their common ground, a starting point for his own questions as to whether human beings can really ever meet on the same terms.

Emma Mandley had a long career in broadcasting and the arts before discovering that what she really loves is translation. She was born and lives in London, and translates from French as well as from Italian. A Friend in the Dark, her translation of a French novel for children by Pascal Ruter, has recently been published by Walker Books. She also translates regularly for the website Books in Italy, where she first came across Fabrizio Coscia’s work.

Emma Mandley had a long career in broadcasting and the arts before discovering that what she really loves is translation. She was born and lives in London, and translates from French as well as from Italian. A Friend in the Dark, her translation of a French novel for children by Pascal Ruter, has recently been published by Walker Books. She also translates regularly for the website Books in Italy, where she first came across Fabrizio Coscia’s work. Fabrizio Coscia was born in Naples in 1967 and is a teacher, writer, and journalist. Among other newspapers and periodicals, he has for many years written for the arts-pages of the daily newspaper Il Mattino. His publications include the novel Notte abissina (Avagliano, 2006), the short story “Dove finisce il dolore,” in the anthology Napoli per le strade (Azimuth 2009, Girulà Prize 2009), as well as Soli Eravamo (Ad Est dell’Equatore, 2015), from which the submitted text is taken, and La bellezza che resta (Melville, 2017).

Fabrizio Coscia was born in Naples in 1967 and is a teacher, writer, and journalist. Among other newspapers and periodicals, he has for many years written for the arts-pages of the daily newspaper Il Mattino. His publications include the novel Notte abissina (Avagliano, 2006), the short story “Dove finisce il dolore,” in the anthology Napoli per le strade (Azimuth 2009, Girulà Prize 2009), as well as Soli Eravamo (Ad Est dell’Equatore, 2015), from which the submitted text is taken, and La bellezza che resta (Melville, 2017).