Three Japanese Poems

April Grammar

That night

We promised

Each other apart

Like artichoke hearts

Then quickly

Cleared the table

And into chairs we

Fell

You

Bundled up the afternoon

And went to climb Mount Sinai

From the bottom of the dark

Stairwell

Up to your room

Hemmed in by dark

Windows

Into the utterly

Laughable futon you

Then fell

The side dish of soaked natane

And grated radish we ate

On your birthday

At dusk

Were the

Botanical adverbs

Of our relationship

We drank sake

In solemn sips

To what we had

The camaraderie of inanimate objects

And the emptiness of

Travel

Piccolo mondo antico

I watched as

People dressed for battle

Walked the wide flat road

Of the Kōshū Kaidō

In my mind

As I woke to

Love in a different era

With nobody around

Just parents

Sitting cross-legged

Grilling rice cakes

With long metal chopsticks

And afterwards

A deaf man forgetting

How to comfort his wife

His wife who was pregnant

I still had plenty of time

To die piece by piece

By checkout time

(Tomioka [1967] 1968: 96-98)

Again Tonight

Everyone has gone home

The winter gathering is over

In no uncertain terms

You lock the door

In no uncertain terms

You wash your hands

The day after tomorrow

All children born

Of woman will die

You break

Everything around you

Starting with

The dishes

(Tomioka [1967] 1968: 95)

Bread

Don’t misunderstand me

If I talk of roses

Instead of bread

I don’t take bread for granted

I simply cannot help myself

It is my disorder: compelled to eat roses

It is because roses are more real

To me than bread

I will eat bread

To keep from starving

I will eat roses

The day before that happens

I can hold out longer than anyone

Don’t blame me for having bread

Blame me for eating roses

(Yoshihara [1964] 1973: 67-68)

四月の文法 [April Grammar]

その夜

われわれは約束した

朝鮮アザミのように

バラバラに

それからいそいで

皿をかたづけ

椅子のなかに

おちた

きみは

ひるまの感覚をたたんで

シナイの山をのぼるのだと

くらい

きざはしをのぼった

くらい

窓にとりかこまれた

部屋の

ちゃんちゃらおかしい

フトンのなかに

それからおちた

うまれた日にたべた

夕ぐれの

菜種のオシタシと

だいこんおろし

は

きみの関係の

植物的な副詞である

もう云うことのない

物質の友情と

ハカナイ

旅行のための

儀式に

酒をすすった

ピッコロ モンド アンティコ

起きぬけのアタマで

眺める

平面の

甲州街道を

いくさの装束をした

ひとびとがいく

だれもいない

時代の恋愛

ひとの親だけが

あぐらをかいて

カキモチを

かね火箸でやいている

それから

ツンボのおとこが

おんなをあやす術をわすれて

おんなは孕んだ

あたしが帰るまでには

バラバラに死ぬひまが

まだあった

では今夜また [Again Tonight]

みんな帰った

冬のひとびとのあつまりはおわった

きみは具体的に

ドアのカギをかけ

きみは具体的に

手を洗った

あさって

女のうむコドモは

みんな死ぬだろう

きみはまず

手もとにある

食器から

こわしはじめた

パンの話 [Bread]

まちがへないでください

パンの話をせずに わたしが

バラの花の話をしてゐるのは

わたしにパンがあるからではない

わたしが 不心得ものだから

バラを食べたい病気だから

わたしに パンよりも

バラの花が あるからです

飢える日は

パンをたべる

飢える前の日は

バラをたべる

だれよりもおそく パンをたべてみせる

パンがあることをせめないで

バラをたべることを せめてください–

Translator’s Note

Tomioka Taeko (b. 1935) and Yoshihara Sachiko (1932-2002) produced some of Japan’s most memorable post-war poetry. Their sophisticated and stunning use of stylistic effects, along with their candid treatment of gender and sexuality, set their work apart from their male contemporaries, yet they remain conspicuously under-translated writers (particularly Yoshihara). It is tempting to suggest this is due to the unusual form of their poetry. Tomioka and Yoshihara both created highly idiosyncratic poetic worlds in which the incompatible is commonplace. Their poems are often confessional in nature, which no doubt explains part of their emotional impact. However, they also draw much of their power from being able to implicate older poetic forms, like the uta, with its fixed poetic vocabulary, while at the same time incorporating modernist influences like free verse and stream-of-consciousness. (It is perhaps no surprise that Tomioka once translated Gertrude Stein).

“April Grammar” is one of several Tomioka poems in which “grammar” is a force with physical consequences. In this dislocated reality, “grammar” takes over the reins from fate. Grammar is responsible for the unexpected, odd twists that a sentence (or an event, or a relationship) must sometimes take in order to make sense. Other Tomioka poems give us the disconcerting feeling that there is no external world at all—that there is just language—and there is no stepping outside of it. Nowhere is this claustrophobic sense stronger than in “Again Tonight,” with its closing of doors and closing of possibilities. The poem also has an important function within Tomioka’s wider body of work, in which she uses a full complement of distinctly gendered personal pronouns, prompting the reader to ask time and again: Is this another speaker? A splinter of the self? A new identity with more expressive potential?

If there are surprises waiting in between Tomioka’s poems, the reader of Yoshihara’s works is liable to feel like he is waiting for and experiencing surprise alongside the poet. There is the distinct sense of something incredible being improvised. The fact remains that Yoshihara yields a lot of the page, by bits and pieces, to the performance of hesitation. A glance at virtually any page of her poetry reveals conspicuous gaps between words, like holes punched out of the text. The effect of reading these pauses is to feel that even the poet is surprised at the word she came up with next, and decided to memorialize that indecision in the structure and typographical look of the poem. “Bread” is a poem in the same vein, but with one crucial difference: the breaks she puts between words and lines are not a record of hesitation or discovery, but a sight guide for how to perform the poem to achieve full rhetorical impact.

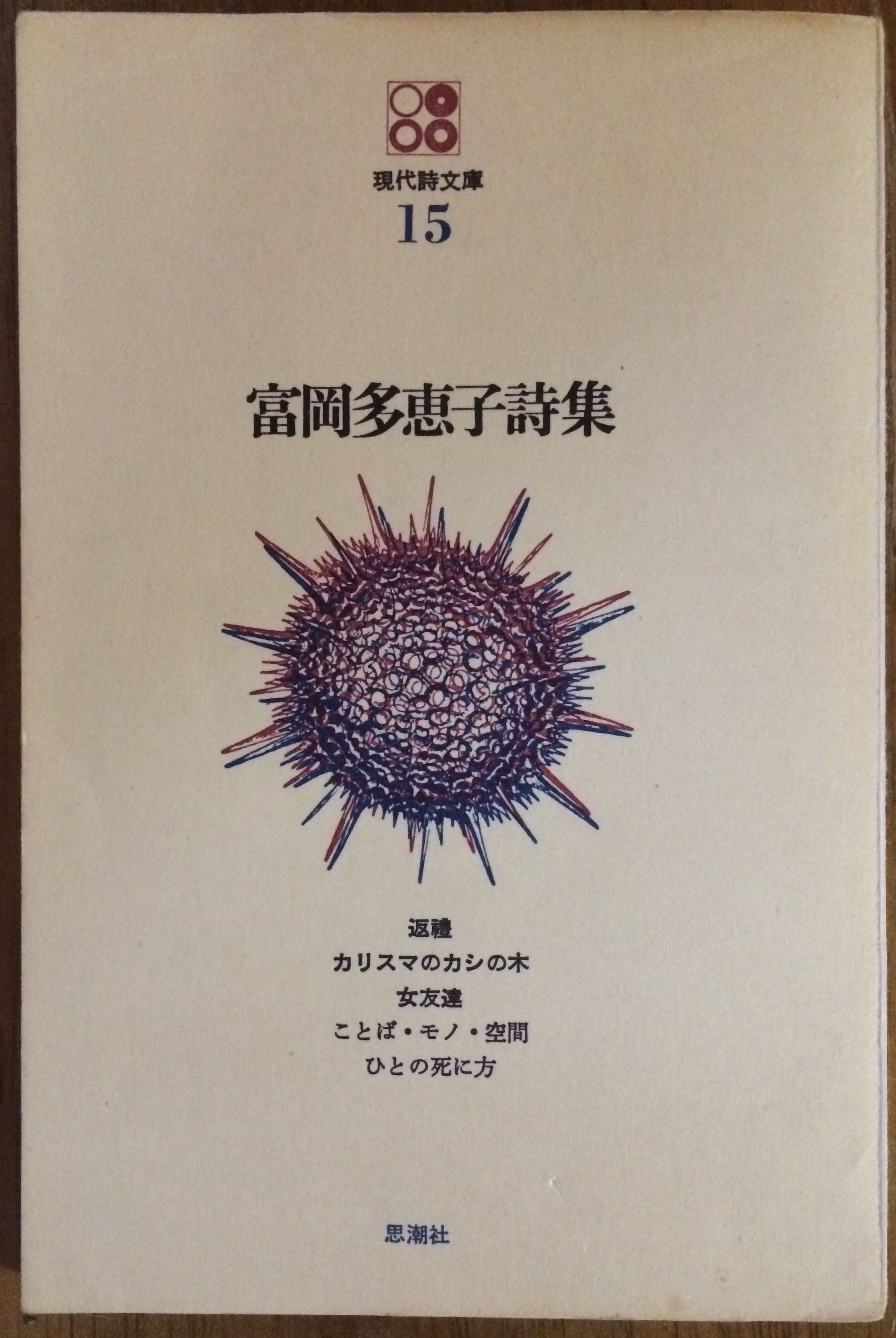

Tomioka Taeko (b. 1935) began her prolific literary career as a poet, publishing five critically acclaimed volumes between 1957 and 1970, after which she gave up poetry for fiction and other genres. A respected critic, she is also known for her work on the script for the 1969 film Double Suicide. The same year, she translated Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives into Japanese. A native of Osaka, she often incorporates Osaka dialect into her writing. (Work cited: Tomioka, Taeko. Tomioka Taeko Shishū. Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1968.)

Tomioka Taeko (b. 1935) began her prolific literary career as a poet, publishing five critically acclaimed volumes between 1957 and 1970, after which she gave up poetry for fiction and other genres. A respected critic, she is also known for her work on the script for the 1969 film Double Suicide. The same year, she translated Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives into Japanese. A native of Osaka, she often incorporates Osaka dialect into her writing. (Work cited: Tomioka, Taeko. Tomioka Taeko Shishū. Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1968.)

Yoshihara Sachiko (1932-2002) published her first collection of poetry in 1964 to critical acclaim. Its themes of motherhood, death, love, and betrayal would continue to inform her work in the years that followed. In 1983, along with fellow poet Shinkawa Kazue, she founded the influential poetry journal Gendai-shi La Mer. The recipient of numerous awards throughout her career, Yoshihara was also an accomplished essayist. (Work cited: Yoshihara, Sachiko. Yoshihara Sachiko Shishū, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1976.)

Yoshihara Sachiko (1932-2002) published her first collection of poetry in 1964 to critical acclaim. Its themes of motherhood, death, love, and betrayal would continue to inform her work in the years that followed. In 1983, along with fellow poet Shinkawa Kazue, she founded the influential poetry journal Gendai-shi La Mer. The recipient of numerous awards throughout her career, Yoshihara was also an accomplished essayist. (Work cited: Yoshihara, Sachiko. Yoshihara Sachiko Shishū, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1976.)

James Garza is a freelance translator and writer living in Japan. His work has appeared in Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine, tNY.Press, and Wild Quarterly, among other places. He holds an MA in Japanese studies from the University of Arizona.

James Garza is a freelance translator and writer living in Japan. His work has appeared in Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine, tNY.Press, and Wild Quarterly, among other places. He holds an MA in Japanese studies from the University of Arizona.